| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

... a superb article.

I'm glad to see that new releases of the piano recordings by Gina Bachauer are forthcoming. In particular, her two MLP recordings of Chopin piano concertos are among my favorites.

An audio engineer specializing in mastering and analog-to-digital transfers, Fine is best known for his current work on the Mercury Living Presence catalog of 300 mono and stereo LPs, most created by his father, recording engineer C. Robert (Bob) Fine, and his mother, recording producer Wilma Cozart Fine. Tom is also a music reviewer for Stereophile and an occasional equipment reviewer for Tape Op magazine.

About those rabbit holes: Reviewing the 5000+ word transcript of our interview for errors and omissions, the mention of a possible future project to create digital transfers of an orchestra's quadraphonic broadcast tapes led to a microscopically detailed discussion of quadraphonic pioneers, machines, relationships, and failed business ventures. A reference to dynamic range inspired one of several minutely detailed clarifications.

The information is fascinating, the trait charming. But if you don't keep your eye on the prize, you could inadvertently follow the white rabbit so far down the hole that you might never find your way back home again.

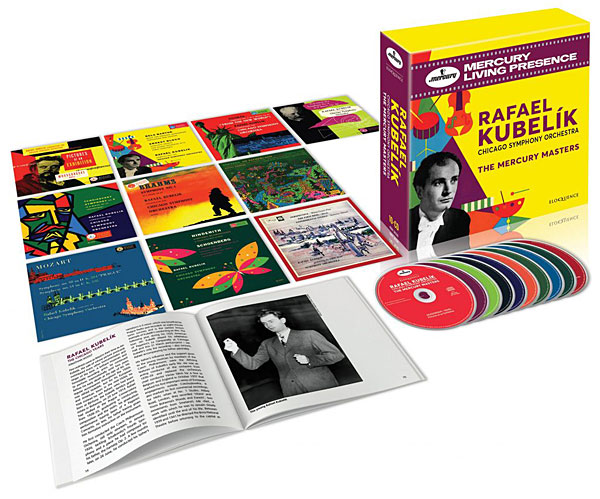

One such prize is Fine's current work with Universal Music Group's Decca and Eloquence labels to create new 24/192 digital remasters of select titles in the fabled Mercury Living Presence (MLP) catalog. Working with tape transfers of the original masters from Jared Hawkes of Abbey Road Studios, Fine has already remastered and produced a 10-CD Eloquence set of the label's complete recordings of Rafael Kubelik and the Chicago Symphony.

Another project coming quickly to fruition is Decca's MLP Vinyl Series 1. Fine prepared a 24/192 master file for each LP side then transmitted the files to Abbey Road Studios where Miles Showell cut the master lacquers at half-speed. ("I do think it's really cool to be working with Abbey Road; I'm a huge Beatles and Pink Floyd fan!" Fine says.) After some careful listening and some back-and-forth, Showell cuts the final master lacquers and sends them to Optimal, the record plant in Germany, where they are plated, stampers are produced, and test pressings are made and shipped to the US for approval. "We haven't had to reject anything yet," Fine said, "but we did find a problem on a stamper that was easily fixed at the plant."

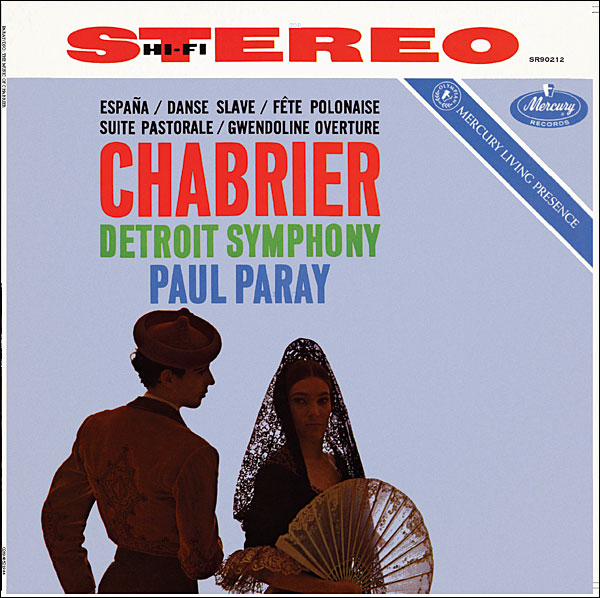

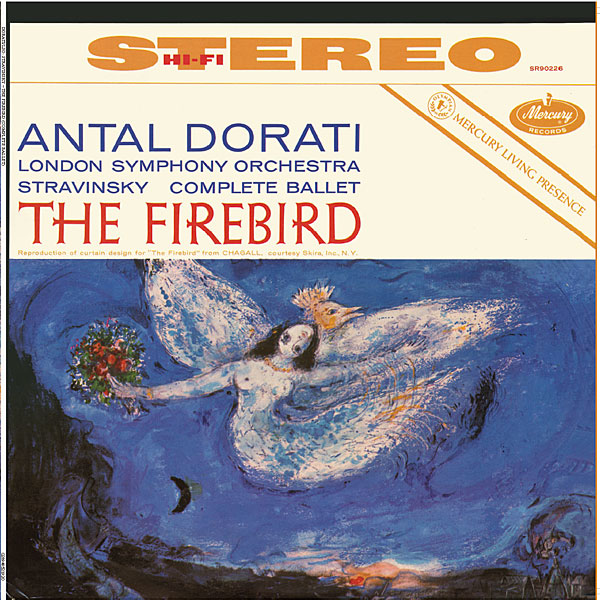

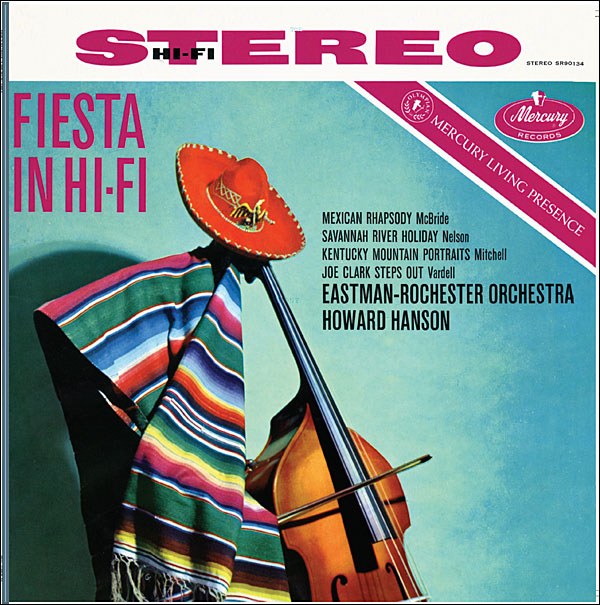

Optimal presses the LPs on premium 180gm vinyl using a compound that's much quieter than that used for the original Mercury LPs—quieter, even, than those pressed at the excellent RCA Indianapolis plant. The new MLP LPs will have high-quality tip-on jackets printed from 600dpi scans of the original covers, with a sticker on the shrink wrap advising listeners to turn up the volume. "It's sort of like the note on the original Rolling Stones Let It Bleed LP: "PLAY IT LOUD," Fine said.

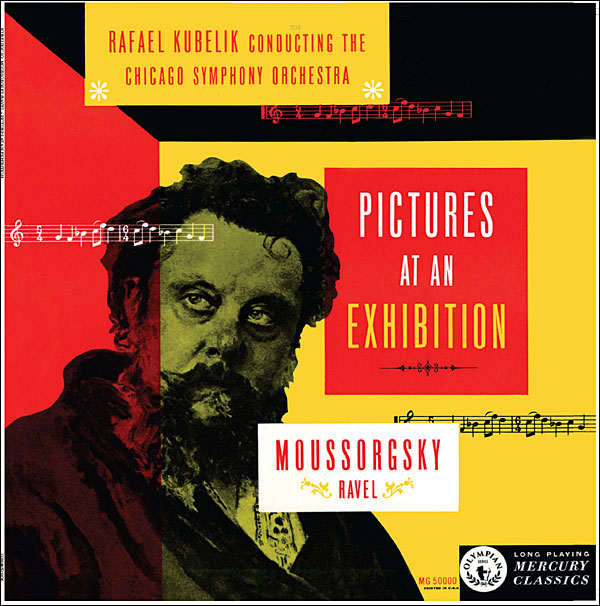

The series includes five titles. One, MG50000, is the mono Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition (orch. Ravel)—the first Mercury "Olympian" series orchestral title, recorded in late April 1951 by Kubelik and the CSO with a single Neumann U47 mike. The rest are stereo mixes made from the original three-channel tapes: SR90134, the equally fabled stereo Fiesta in Hi-Fi from Howard Hanson and the Eastman Rochester Orchestra, recorded October 28, 1956, with a Schoeps M201 in the center and Neumann U47s on the left and right; SR90212, The Music of Chabrier by Paul Paray and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, recorded November 18, 1960, with three Schoeps M201s; SR90226, Stravinsky's The Firebird from Antal Dorati and the London Symphony Orchestra recorded June 7 and 9, 1959, with three Schoeps M201s; and SR90518, A Flamenco Wedding Party by The Romeros with singer Maria Victoria, recorded December 27–30, 1966. All were remastered from first-generation master tapes with none of the dynamic processing and added echo that marred some prior rereleases from some sources.

Next up: two-CD box sets of the complete Paul Paray/Detroit Symphony recordings 1952–1961 on MLP, due from Eloquence in the first quarter of 2022. An Eloquence CD box of pianist Gina Bachauer's complete MLP catalog is also due early in 2022. The five titles to be included in MLP Vinyl Series 2, projected for release during the second quarter of 2022, had not been set by press time, but in the dCS podcast Trust Your Ears, Hawkes mentioned transferring the 3-track master for SR90288, Ernest Bloch's Sinfonia Breve and Wayne Peterson's Free Variations from Dorati and the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. This will be the first reissue of Peterson's work. Byron Janis's famed solo piano rendition of Pictures at an Exhibition, which was only released on CD from Wilma Cozart Fine's 16/44.1 master, will also receive a new 3–2 remix in 24/192.

Also in the early stages is a pair of box sets of the complete Antal Dorati/Minneapolis Symphony recordings, due in the fourth quarter of next year. Fine is planning one or two boxes of the complete Eastman Rochester recordings: Howard Hanson, Frederick Fennell, A. Clyde Roller, Donald Hunsberger, and some odds and ends from the Mercury Golden Imports era in the early '70s. And let's not forget the dozen or two MLP albums that have yet to see digital release, which Fine hopes to reissue in streaming-only format and possibly in small CD sets.

MLP

The Mercury Living Presence series takes its name from New York Times chief critic Howard Taubman's review of Bob Fine's first orchestral recording for Mercury Records, the 1951 Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition. It was "like being in the living presence of the orchestra," Taubman wrote, about a recording that was made with a single microphone hung 10' above conductor Rafael Kubelik's head in Chicago's Orchestra Hall.

"The Mercury Living Presence recordings did not try to replicate the sound at a live event," Tom Fine says of his parents' work. "They're a produced product. The perspective's focus is sharper and more detailed than any place but above the conductor's head; you can't experience the same thing live. You're hearing more of what the conductor's hearing, but in a balance that's reproduceable and makes sonic sense on a home system. I think that was the point of the technique: to bring the listener closer to the music than they could get in the concert hall."

Bob Fine let himself be guided by the size of the orchestral forces, the dimensions and construction of the hall, and the nature of the music. For mono recordings, a single microphone was used. For stereo, Fine recorded three channels, with a central microphone a dozen feet or so over the conductor's head and two peripheral mikes arrayed in front of the orchestra. Microphone outputs were fed to ½" 3-track tape or, between 1961 and 1963, 35mm magnetic film, which both Fines believed sounded better (footnote 1). No limiting, boosting, equalizing, mixing, or touch-up altered the conductor's vision. (If the dynamic range was greater than the equipment of the time could handle, Fine would ask the conductor to limit dynamics rather than mechanically adjust the gain.) For final release, Wilma mixed the edited 3-track master tape down to a 2-track lacquer.

To overcome treble die-off in halls, Mercury used sensitive German condenser microphones that have a pronounced presence peak. Mikes were placed far enough away to capture the bloom without losing location cues and without excessive brightness. "That's how you can hear the detail of every violin in a section rather than just a wavefront of violins," Tom Fine said. "When done best, in the right halls, it's really amazing because you can hear into the arrangement [and perceive] how everything's moving around. Other engineers in the '70s captured detail with lots of microphones, but they had to reconstruct the ambience or create it out of thin air, as in the later recordings that used time delays on the microphones. That's a far more complicated way than hanging one microphone for mono and three microphones for stereo.

"My father was constantly experimenting and trying new things in different places at different times in the mono era and continued to do so in the stereo era. His team didn't release recordings that didn't sound good, but they took different approaches as their technique evolved. Fiesta in Hi-Fi was recorded less than a year after they started recording in three-microphone stereo and was the second time they used a three-microphone setup in Rochester. At the time, they used Neumann U47s on the side and a Schoeps M201 in the middle. You will notice that Fiesta sounds very different than the Chabrier or Stravinsky Firebird recordings, which were done years later with three Schoeps M201s in London and Cass Technical High School in Detroit."

"By that time, they had really settled on a recording system. The recordings from about 1960 onwards are more similar than different. Once Philips bought Mercury, they started cutting the budget from day one. That's why they concentrated on the London Symphony in Watford; it was cheaper to record, they could play anything excellently, and Mercury's star conductor, Dorati, moved over there."

Wilma Cozart Fine's remasters

After the final Mercury recording session with the Romeros and the San Antonio Symphony in November 1967—neither Fine took part—a number of LP issues of varying quality began to appear. In 1989, seven years after Bob Fine's death, Philips/Polygram asked Wilma Cozart Fine to digitally remaster the MLP catalog. After almost a year of research, she chose the dCS 900 A/D converter. Using a digital bus designed by Daniel Weiss, transfers were down-converted and preserved solely as 16/44.1 on U-matic videocassettes, the storage medium of the Sony PCM-1630 audio processor, which was very common at the time.

For tape playback, Wilma Cozart Fine used a restored Ampex 300 3-track tape machine similar to the original Ampex used by MLP, along with her custom Westrex 3-2 channel mixer. She also commandeered the original Westrex 35mm film machine used by Mercury in the '60s. Over a 10-year period, she worked with Dennis Drake and later engineer Andrew Nicholas to produce more than 100 CDs from approximately 150 MLP LPs.

According to Tom, as the '90s progressed, Polygram and the other CD manufacturers began to utilize very accurate clocking at the glass-master stage to better control jitter. Today, manufacturers send a bit-perfect image of the CD to the pressing plant and cut the glass master at high speed (footnote 2), with MD5 verification at each stage of production. "Between manufacturing the CDs better and playing them back better, my mother's CDs sound better today than they did on 1990s players," he affirms. "We understand jitter, reclocking, buffering, and how to grab data off CDs much better. When you use bit-perfect software to rip my mother's CDs to a computer and you play the files, you get even further away from the original problems.

"I think most of my mother's CDs really stand up to modern reissues, except you can never sell them as high-resolution files. That's basically all that's missing, in my opinion. That said, there are cases where we're doing new remasters of her work. One example of a rather well-liked recording that I've remastered for a second time is the Saint-Saëns "Organ" Symphony No.3 that I did for the Marcel Dupré box (Marcel Dupré: The Mercury Living Presence Recordings, Decca Classics 478 838, footnote 3). Reviewers cited it as a very good remaster. I'm very proud of it. It was a very problematic tape; we had to do some major tricks in the digital realm to fix places where the oxide had fallen off the tape around a splice.

Footnote 2: The "glass master" is the CD equivalent of the "stamper" used to produce vinyl records.

Footnote 3: The Detroit Symphony Chabrier and Dorati Firebird are also second digital remasterings.

... a superb article.

I'm glad to see that new releases of the piano recordings by Gina Bachauer are forthcoming. In particular, her two MLP recordings of Chopin piano concertos are among my favorites.

Of course, JVS once again will cause me fiscal pain!

Standing ovation for this one!

Absolutely wonderful stuff.

PS: I seem to remember that Art Dudley sniffed at MLP? Any idea why?

but Tom Fine must be aware that a lot of audiophile analog listeners will not buy the new releases, because digital domain is involved. I know, it is not fair that people, like me, have no interest in vinyl involving digital steps, when originals can be found that are all analog. I wonder, whether the market for classical music is that big, that music publishers can afford to neglect the (for sure very annoying) fact that analog lovers are so stubborn regarding the mastering process. Annoying, because I know that digital can sound amazing or better than analog, but still stick to analog only.

..buy vinyl only when some deeply obscure recording is unavailable in decent digital form or when the cd or streaming version truly sucks, given that many a time the vinyl-oriented digital source is actually the 24/96 master. I have found however to my utter surprise that some cds and lps cut from exactly the same analog or digital master - which is rarely the case - can sound almost identical.

Even better would be a direct mix to 15 ips 2-track tape, for those who appreciate only the best analog sound reproduction.

I have a few original 2-track tapes made from 35mm sessions recorded at Fine Sound in the '60s, and they make vinyl records completely obsolete. They also sound much better than any CD... remastered, remixed, re-edited, or regurgitated.

I have loved the Mercury Living Presence LPs for ages. I met Tom first through an appeciation of his loving restorations, and recently used him to copy a vinyl album to a digital high rez format. His work is masterful. Thank you for this article.

Wilma Cozart Fine's MLP CDs are still held in high regard. I had fun collecting those and the RCA LS SACDs back in the day. It's a smart move to produce MLP box sets, I wonder why nobody thought of that before! Excellent article, keep 'em comin'.