| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

There Lies the Disc, the making of the new Cantus CD The Sound

John Atkinson on Capturing the Sound

As I had recorded Cantus in the Washington Pavilion's Great Hall in Sioux Falls back in 2003, for the group's Deep River CD, I had a good idea of where I was going to place the three distant microphone pairs for my main pickup. An almost coincident ORTF-arranged pair of DPA cardioids would capture the soundstage, a wide-spaced pair of Earthworks omnidirectionals would add bloom and spaciousness, and a more distant pair of high-voltage DPA omnis, mounted either side of a Jecklin Disc from Coresound and fitted with their special acoustic equalizers, would allow me to balance the direct and reverberant soundfields in the mix. (For details about how and why I record Cantus the way I do, see my earlier articles, reprinted here, here, here, and here.)

Footnote 1: After an unfortunate but unavoidable delay, this CD, described in the May 2006 issue of Stereophile, is now available from the magazine's secure "Recordings" page.—John Atkinson

As I had recorded Cantus in the Washington Pavilion's Great Hall in Sioux Falls back in 2003, for the group's Deep River CD, I had a good idea of where I was going to place the three distant microphone pairs for my main pickup. An almost coincident ORTF-arranged pair of DPA cardioids would capture the soundstage, a wide-spaced pair of Earthworks omnidirectionals would add bloom and spaciousness, and a more distant pair of high-voltage DPA omnis, mounted either side of a Jecklin Disc from Coresound and fitted with their special acoustic equalizers, would allow me to balance the direct and reverberant soundfields in the mix. (For details about how and why I record Cantus the way I do, see my earlier articles, reprinted here, here, here, and here.)

An added complication for this project resulted from the fact that for six of the works, Amy Beach's Sea Fever and the five Stanford Songs of the Sea, the singers would be accompanied by a piano. There would also be a solo cello in "Break, Break, Break," an original work by tenor Brian Arreola, while the cello would be joined by acoustic guitar in Gordon Lightfoot's "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald." Given my druthers, I prefer to get an optimal balance by moving singers backward and forward; while this worked with the balance between soloist Kelvin Chan and the backing choir in the Stanford, the best places for the distant mikes when it came to capturing the voices made the solo instruments sound too reverberant. I decided, therefore, to use a close pair of cardioids on the piano, aimed at the strings with the Steinway's lid on its short stick, and an omni close to the cello's right-hand ƒ -hole. This way, by mixing in the output of the spot mikes about 12dB below the level of the main mikes, I could add a little focus and presence to their sounds without disturbing the overall balance.

"The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" was a little more problematic. The guitar was being played by baritone Alan Dunbar, who would also be singing solo on this track. To capture his voice I ended up using a single spot mike, a tubed Neumann cardioid, which also picked up enough of the guitar's sound. Before setting up the solo mike, we again did a lot of "Back a bit more, Alan—er, no, I mean forward a bit" to optimize the balance of Alan's solo voice with the sound of the accompanying choir.

The big change from previous projects for There Lies the Home was that I decided to dispense with tape. Instead, I would record direct to an external hard drive connected to my Apple Titanium PowerBook, using the beta Record Panel in Metric Halo's ConsoleX software for the FireWire-connected MIO 2882 and ULN-2 A/D converters, which stores each channel as a mono Sound Designer 2 file. I had recorded sans tape before, for the Robert Silverman Diabelli Variations project in 2004 (footnote 1), but that was just two channels. For There Lies the Home, I would be recording as many as eight tracks at 88.2kHz sample rate and 24-bit word length. However, these would be well within the capabilities of my laptop. The only complication was that the FireWire interface doesn't have enough bandwidth to deal with both the Metric Halo boxes (which require bidirectional communication of all the audio channels' data) and an external drive. I hung the latter, therefore, off of a FireWire card plugged into the laptop's PC Card slot.

At the last minute, as I was about to load all my gear into my wife's Land Cruiser, I lost my nerve and packed three two-channel recorders, which I would use to back up the three main pairs of mikes as we went along. This way, if the external hard drive went bad (as they have been known to do) or the laptop misbehaved (also not unknown), I wouldn't lose what we'd done.

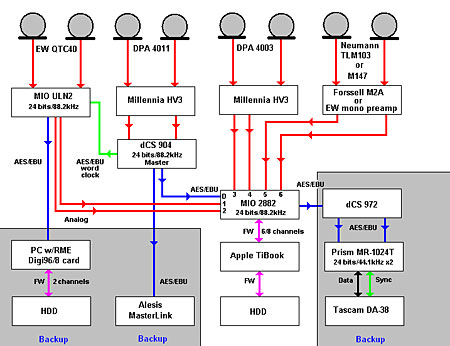

The complete rig is shown in block diagram form in fig.1. A dCS 904 converted the outputs of the cardioids to digital and supplied a master 88.2kHz word-clock signal to the two Metric Halo converters: the feed to the MIO 2882 carried the cardioid channels, the feed to the ULN-2 a reference clock signal (without any audio data). A second AES/EBU output on the dCS converter backed up those channels on an Alesis MasterLink hard-disk recorder.

fig.1

Although all the input channels of both the ULN-2 and the MIO2882 showed up in the Metric Halo software's Record Panel, I wasn't confident that I could get error-free data from the ULN-2 with the OS X generation I was running at the time (footnote 2), so I used it only as a low-noise mike preamp, taking a feed from its analog outputs to two of the MIO 2882's eight analog inputs. (I did use the ULN-2's own converters to feed one of the backup recorders via AES/EBU, however.)

The signals from the third pair of mikes were fed from the MIO 2882's AES/EBU output to a Tascam DA-38 multitrack tape recorder, using a combination of a dCS 972 digital-digital converter and a PrismSound MR-1024T multiplexer to spread the two channels of 24-bit/88.2kHz data over the recorder's eight 16/44.1 channels. These mikes were the high-voltage DPA omnis, which I was amplifying with a Millennia Media HV3B.

Footnote 1: After an unfortunate but unavoidable delay, this CD, described in the May 2006 issue of Stereophile, is now available from the magazine's secure "Recordings" page.—John Atkinson

Footnote 2: A groundless fear, it turned out, but when you're on location in what, to a New Yorker, is the back of beyond, you become really cautious regarding what will work.—John Atkinson

- Log in or register to post comments