| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The Survivalists: Mosaic and Newvelle Records Page 2

"I have regrets about CDs. I mean, I wish to God they hadn't rushed into the market. I wish they'd waited till they could make 20- and 24-bit CDs before they hit the market. If I sit in a studio and flip back and forth between analog and 24-bit, you'd be hard put to tell the difference in most cases—24-bit is sublime."

Cuscuna thinks that perhaps the next logical, the most compact and convenient physical medium is the USB thumb drive, but admits that there's nothing sexy about them. "I remember when Universal was gonna be ahead of the curve, and there was some new thing they were going to be issuing, and they sent out promo samples to the stores, and they sent it on a thumb drive. No one knew what to do with it, and everybody threw it out."

Cuscuna says he never saw the return of the LP coming. "In the 2000s, when LPs started quote-unquote coming back, their sales numbers were still pathetic. In the '90s, major labels would have said, 'Oh my god, who gives a fuck about 2000 units? That's bullshit, why waste our time?' By the 2000s, they were looking at 2000 units like, 'Oh, thank god, a little more business.'

"At Blue Note in the late '90s or early 2000s, I started putting out 120gm vinyl, for ten bucks a pop, of Lou Donaldson and Grant Green and Jack McDuff—soul records that were being heavily sampled, because young kids wanted something they could afford and have fun with. So there's that side of vinyl.

"Then there's the guys who made a lot of money in their life, and some of them have $70,000 model-train layouts in their basement, and others have $60,000 hi-fi systems, and they have $15,000 turntables and they want great vinyl. So there are labels, like Music Matters and Mobile Fidelity and Chad Kassem's labels, that will give them what they want, and they don't care what it costs. So that's the $30-tier LP. Now that layer, the audiophile layer, has grown some, to the point where I just worked on a new Miles Davis box, Freedom Jazz Dance: The Bootleg Series Vol.5, and even a year ago, Columbia would have farmed out the vinyl to this Dutch company. Now they're putting out the vinyl version—they think it's worth doing themselves. So this thing that I thought was going to be a flash in the pan seems to have legs."

Speaking of legs, does Cuscuna feel rosy about the future? He says he's excited about Mosaic's next big CD box, Classic Savoy Be-Bop Sessions 1945–49, which will include everything recorded for Savoy except the sides cut by Charlie Parker, which Cuscuna says are currently in print in a variety of reissues.

"One of the reasons that majors don't want to do material from the '30s, '40s, and early '50s is because, in the rest of the world—not the States—it's public domain. So they don't think it's worth bothering, because all these quote-unquote legitimate public-domain labels in Europe are cranking this shit out for free. But they're not putting out previously unissued material, and they're not putting out transfers from the original sources. So our feeling is, we keep doing it in a definitive way with the best possible sound, and people will always prefer what we're offering."

Newvelle Records

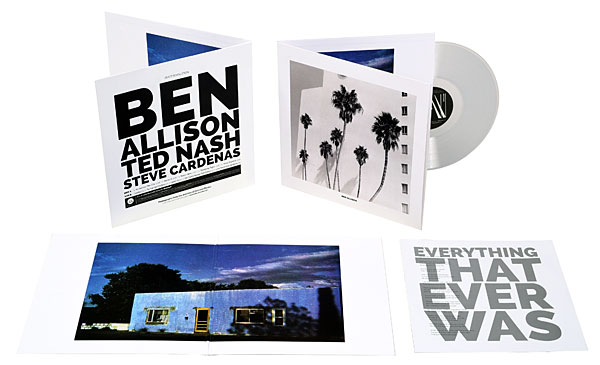

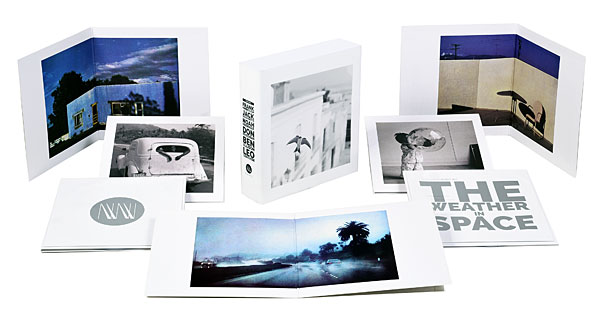

Earlier this year, a Frenchman, Jean-Christophe Morisseau, blind e-mailed me to introduce himself and explain that he and an American partner who knew jazz, pianist Elan Mehler, were starting a record label focused on recording new jazz and creating a "luxury" product. A meeting with both men followed. They planned packages containing a 180gm LP pressed on transparent vinyl at the MPO plant, just outside Paris; an original poem by American poet Tracy K. Smith printed on the record sleeve; and a photo from the archives of Bernard Plossu across the inner gatefold.

Skepticism is too weak a word to describe my reaction. A grand dream of starting a record label, particularly one recording new music rather than reissues—and jazz, which is not a huge seller—is a sad tale I'd heard many times before. Signing artists and selling music that you love sounds like a charming way to spend your time, until the realities of distribution and sales become painfully clear. Most labels, thankfully, never get beyond the excitement of brainstorming—which I admit to having indulged in a time or two myself. Most of those that do collapse after losing a lot of money, and leave nothing but debt, bad feelings, and rooms full of unsold records.

"I know that the industry is on fire and everyone is jumping ship," Mehler, who produces the records, says over the phone from his home in Boston. "But I see this rise in vinyl, and I see real opportunities there. Two years ago, everybody was downloading, and now downloads are nothing. It's all about streaming. And you also see this desire to return to something tangible. The physical thing, and [Newvelle's] subscription thing, sort of play into that, because people want to be in these communities."

The future of Newvelle Records hinges on whether or not Morisseau and Mehler can build a sustainable subscriber base using the subscription model they've chosen. A year's worth of six albums costs €325 (about $360). The artists in the first season were all young New York post-bebop cats: the Ben Allison Trio, Don Friedman Trio, Leo Genovese Trio, Frank Kimbrough Quintet, Noah Preminger Quartet, and Jack DeJohnette (solo piano).

"I like this idea of community and building a membership base more than just buying a record here and buying a record there," Mehler says. "It's really about telling a story over six different records. So, as a producer, it's much more exciting and rewarding to be able to have this bigger canvas to build over. The artists have six records to play with, the poet has six. There's space to build something. It's like having an orchestra instead of having a trio, from a producer's standpoint."

Mehler met Morisseau in Paris, when he was hired to teach him how to play blues piano. "We went out for lunch after a lesson, and I told him about this idea, and he sort of, like, lit up. This is an idea I had a couple years ago, seeing the rise of vinyl and seeing a couple record clubs that weren't recording new music. Jean-Christophe has serious national sales experience. He got excited about it, about doing stuff within the luxury market. We started putting some muscle behind it, started meeting twice a week to draw up plans."

The project got off the ground with a Kickstarter campaign that raised over €34,000. The recordings are all being made at East Side Sound, in New York City, by engineer Marc Urseli, and mastered by Scott Hull, at New York's Masterdisk. So far, the sound is very good—very live and close-miked. Mehler does all of the label's A&R himself.

"I like strong melodic content. I like to go and hear somebody blow for 17 minutes or something, but that's not my thing on record. I like that vinyl gives you the chance to make short pieces. It's where my head is at these days [as a player]. The solo record I did two years ago has 17 pieces on it, and nothing is over three-and-a-half minutes."

Having listened to parts of each of the first six records, I can't say I hear any sameness that could be called a "Newvelle sound." Mehler agrees. "I don't give a huge amount of direction, but I am choosing my taste. I'm only working with musicians whose music I love. So, organically, there's going to be a sound that goes across it. And what I really love about the series—which I sort of anticipated, but I'm really glad to see come true—is the little kismet, the little sparks that happen, even though they're not planned. Noah [Preminger] had Ben Monder on the record, and this was before Ben had recorded with Bowie, so we knew nothing about that. So Ben is featured on both records—Bowie's last record and Noah's record. It's these weird little sparks that are really exciting."

As of this writing, the second year's campaign was well under way on Kickstarter. In 2017, the 2016 series of LPs will be available individually from www.newvelle-records.com. If you become a new subscriber in 2017, you get a discount on the 2016 releases.

Perhaps what Mehler, a player himself, is most proud of is that Newvelle attempts to do right by musicians—something that's rarely been a concern of most record labels, past or present. "A big part of what we are doing is a model for the musicians. They agree to give us a two-year window at being exclusive, then they can do whatever they want with the music. We'll give them the tapes, and they can re-release on a different label, they can release on their own label, they can put them up on YouTube. We're very transparent. That's why musicians are coming to us, and why people like Jack DeJohnette agreed to do it, outside the quality of the production."

While I'd bet against most labels surviving even their first year, if Newvelle Records keeps up the quality of both its LPs and the music on them, they may have a fighting chance to someday, like Mosaic, celebrate their thirtysomethingth anniversary.

Mehler and Morisseau's planning even extended to the name. "We bounced around a lot of ideas, and everything seems to be taken. Newvelle is new. It's the feminine word for new in French, spelled nouvelle. And then, because this is really about a New York sound and New York scene, we wanted to get New York in there. And then, of course, we have vinyl with a v."

- Log in or register to post comments