| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

http://www.harmoniamundi.com/#!/albums/2466

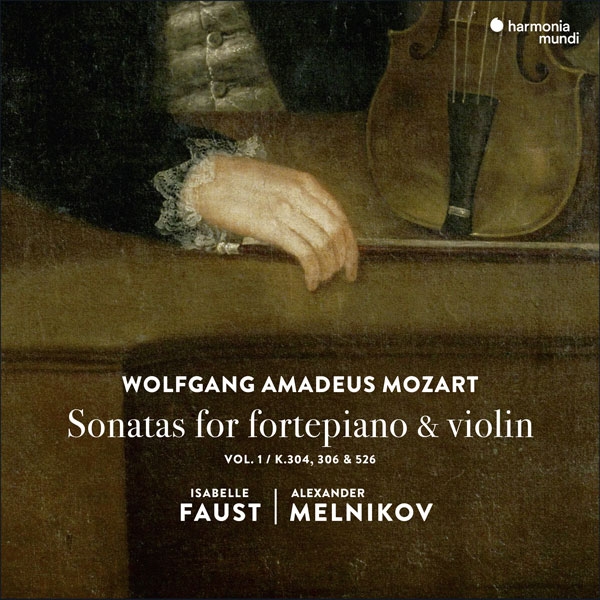

It's one thing to hear Mozart's sonatas performed on modern instruments. Arkivmusic.com, for example, lists 53 recordings for one of the three sonatas in Faust and Melnikov's Vol.1, the Sonata for Violin and Piano in A, K526, and most of the recordings feature modern instruments. Only a relative few—Rachel Podger and Gary Cooper, Thomas Albertus Irnberger and Paul Badura-Skoda, Jean-François Rivest and David Breitman, and Sigiswald Kuijken and Luc Devos among them—attempt to recreate the sound of gut-stringed, baroque violin and fortepiano that Mozart was familiar with.

The ability to hear that sound without compromise is one of the best arguments I can think of for investing in the highest quality components you can afford without risking eviction, foreclosure, bankruptcy, or a severed relationship. When I listen on an extremely resolving desktop/small room system—Macbook Pro streaming Tidal via either Audirvana or Amarra–>Nordost Odin and Odin 2–>Dynaudio Focus 200 XD powered loudspeakers abetted by a Nordost QKore and QB8—I certainly hear the tangy, piquant sounds of Faust's gut-stringed Stradivarius and Melnikov's modern (Kern) replica of a 1795 Walter fortepiano. But it's only when I turn to my reference system—NUC with Roon–>dCS Network Bridge–>EMM Labs DV2 DAC (here for review)–>D'Agostino Progression monoblocks–>Wilson Alexia 2 plus all of the above and a PS Audio P15 Power Plant—that I can hear the virtual symphony of undertones and overtones that make the sound of these extremely colorful period instruments so enticing.

Auditioned in 24/96, the recording is a feast for the senses, or at least those senses that prefer tang and spice with their sweetness. The Sonata in D K306—part of a group of six sonatas that Mozart completed in 1778, the year in which he turned 22—gallops out the gate, whizzing by as it dusts everything in its path with joy. Once you get over how fast Melnikov is playing, and how much delight both musicians take in every trail of notes as they dash up, down, and all over the place, you can begin to contemplate the inventiveness and subtle shifts that make these sonatas so interesting.

Written before it, also in Paris, the two-movement Sonata No.4 in e, K304, spends much of its time dwelling in the minor. Although I could do without every single variation and repetition in its opening Allegro's 10:02, it's clear that Mozart was having a ball seeing how much he could do with his material. The work is certainly different than Mozart's five other sonatas for violin and fortepiano from the same period, and breaks a lot of "rules" as Mozart lets his imagination lead him into unexplored territory.

Mozart composed his final Sonata in A for Violin and Fortepiano K526 in 1787, at the same time he was finishing Don Giovanni. Proof can be found in the final Presto, which borrows a bit of melody from Don Giovanni's "zipping right along, now you hear it / now you don't" Champagne Aria ("Fin ch'han dal vino"). But you won't care about proof when you hear this sonata's more mature approach to joy—a joy tempered with the wisdom born of challenge and struggle. For Mozart lovers, this recording is indispensable.

http://www.harmoniamundi.com/#!/albums/2466

"Although I could do without every single variation and repetition in its opening Allegro's 10:02..."

Taking all the repeats in period-instrument performances is often criticized by those who prefer modern instruments. But, especially in large-scale orchestral works, I find a helpful visual analogy in classical architecture. Like the repeating rows of columns, arches, or flying buttresses, the repeats in music, such as in Mozart's 'Prague' symphony, are part of what gives them their wonderful grandeur. And in the first movement of Beethoven's Eroica, the first repeat helps establish--and deepen--the opening mood, so that when the powerful, slashing dissonances of the exposition arrive, the sense of contrast and development is even greater, and the stage has been better set for such powerful tensions.

Symphonies are sometimes called 'cathedrals in sound.' But one arch does not a cathedral make. Something to keep in mind when listening to repeats in Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven. Best regards.

"The ability to hear that sound without compromise is one of the best arguments I can think of for investing in the highest quality components you can afford without risking eviction, foreclosure, bankruptcy, or a severed relationship."

The ability to hear that sound without compromise is one of the best arguments I can think of for investing in a membership in the San Francisco Early Music Society. If you're fortunate enough to be in that neighborhood, it's a world center for Early Music performance, with a lot of performances via Cal Performances, in Berkeley.

that they're not mutually exclusive?

They're also not necessarily equally the case. Case in point: Seattle Symphony's latest recordings sound better on a good system than when those works were heard live in the hall. Engineer Dmitry Lipay knows just how to compensate for the hall's sonic deficiencies.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone.

jason

I was thinking more in terms of the difference of the sound of "original instruments" [almost always replicas, but let that pass] and how the delicacy of that sound so easily curdles when recorded. Harpsichords being a case in point. Also noting how so many people who listen to "classical" [whole lot of different eras there] music have not been directly exposed to the sounds of earlier iterations of familiar instruments. I have little doubt that there are auditoria that can ruin sound, I did a lot of recordings at Zellerbach Hall, another one of those places where an engineer can come up with better sound than what an auditor would experience mid-hall.

Ugh. I couldn't even distinguish the Vienna Philharmonic's distinctive sound in Zellerbach. Only when I followed them up north, to Green Hall, could I savor what makes them so special.

https://theviolinchannel.com/isabelle-faust-mozart-sonatas-fortepiano-violin-cd-alexander-melnikov-harmonia-mundi-records/

Faust/Melnikov played the Mozart violin sonatas over one weekend last October at the Wigmore Hall. I heard two of these sonatas in one of these recitals. It takes dedication to go to two recitals starting at 11:30am in one weekend and then in the evening. I was listening to their Beethoven violin sonatas set last night - it's a modern classic. I heard Ibragimova/Tieberghen play all the Mozart sonatas at a more leisurely pace over several midweek evenings. Very fine performances and excellent recordings. One of them is top of the list here:

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/feature/the-50-greatest-mozart-recordings-3

These sonatas are a fine body of work when listened live played well as a complete set.