| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

On The Road Again: Three European Jazz Festivals

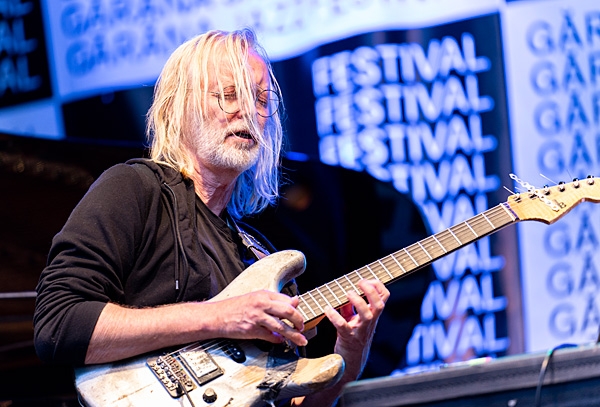

Eivind Aarset at the Gărâna Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

The first European jazz festival I ever attended was in 2006. It was the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy, one of the biggest. Tens of thousands of people overran the cobblestone streets and piazzas of Perugia's old town. The music began before noon and ended long after midnight. At the end of 10 days, I was delirious from joy and sleep deprivation.

I was also hooked. I had to go back. I have now been to more than 50 European festivals in 13 countries. They are all different, but they have one thing in common: They all prove that many of the most important developments in jazz are now happening in Europe.

Phil Freeman is right: European jazz is "its own separate/special thing." In the 21st century, European artists are integrating their own cultural histories and national imageries into their music, bringing the fresh energy and innovation on which jazz depends. Many American musicians play European festivals, and often they are headliners, but European players dominate the programs.

I didn't understand any of this until I started going to European festivals. They are the surest, most efficient, and most fun way to get in touch with the European jazz scene. And the festivals are not hard to find. Their proliferation across Europe, especially in summer, is astonishing. All the major cities, and hundreds of minor ones, have their own jazz festival.

In 2020, the pandemic stopped world travel in its tracks, including mine. For the first time in 15 years, I did not leave the United States, in 2020 or 2021. Given the scale of the suffering COVID has inflicted on the world, missing out on travel opportunities is barely worthy of mention. Still, it hurt not to go.

By 2022, I was ready to go out again. Early in the year, I lined up a trip with three stops. As the date of my departure approached, in late June, I was getting nervous. COVID variants and surges were in the news, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine was horrifying the civilized world. One of the countries on my itinerary was Romania, which borders Ukraine.

But I went. My first destination was the new Monheim Triennale, in Monheim am Rhein, a town of 43,000 on the Rhine river, between Dusseldorf and Cologne in western Germany. The Triennale had intended to launch in 2020, but the pandemic delayed the festival's premiere for two years. It was billed not as a jazz festival but a "contemporary music festival."

The Monheim Triennale's artistic director is Reiner Michalke, best known for running the highly regarded Moers Festival in Germany from 2006 to 2016. "When I took over Moers, I was aware that it had a certain history, a tradition, that I needed to respect. But the Triennale was a blank sheet of paper," he told me. Michalke came up with a concept that was novel and ambitious. With the assistance of a committee of curators, he chose 16 artists and invited them "to dream." He commissioned each of them to create a "Signature Project." Not all were jazz musicians. There were people from world music, rock, classical, and electronic music. But jazz, and certainly improvisation, was central to the Triennale's gestalt.

Michalke secured the funding to carry off his idea with class. (The largest contributor, at €1,500,000, was the city of Monheim.) A big new "eventschiff" (event ship), the MS RheinGalaxie, docked on the river below the town. Its auditorium, all gleaming chrome, glass, and hardwood, is where most of the Signature Projects were performed.

Marcus Schmickler "Entwurf einer Rheinlandschaft," Monheim Triennale. Photo by Niclas Weber.

On the night of June 22, in the 9:30pm twilight, the festival commenced with a work called "Entwurf einer Rheinlandschaft" ("Concept of a Rhine Landscape") by Marcus Schmickler. It was not a concert but an installation, an outrageous happening. It took place in a traffic circle in the town, directly above where the MS RheinGalaxie was docked. Its many episodic elements included a trombone section on the balcony of a building exchanging calls and responses with a trumpet section on the rooftop of a building across the circle. Groups of spoken-word artists paraded around the circle. Choirs sang. Percussionists drummed. An orchestra of 18 accordions wheezed softly. At one point, lights came on over a small stage and a rich baritone voice began singing. (The program identified her as Lucia Lucas, the first transgender opera singer to perform at the New York Met.) Several hundred festival attendees and curious Monheim townspeople, some licking ice cream cones, wandered around, staring at the shifting spectacle. When a dog barked, it became part of Schmickler's script.

Michael Beharie, Alex Zhang Hungtai, Maria Kim Grand, Justin Frye, Greg Fox, Monheim Triennale. Photo by Niclas Weber.

The other 15 Signature Projects had a tough act to follow. Many succeeded. Sam Amidon sings and plays guitar, banjo, and violin. His diverse career has been based mostly in Americana and country music, but he had always wanted to play with cutting-edge avantgarde jazz guitarist Marc Ribot. Their improbable joint venture caught fire, especially a wailing, snarling version of John Coltrane's "Drum Thing." Art-rock guitarist Ava Mendoza gave a powerful solo recital. Her collaborator, video artist Sue Slagle, offered vivid visual responses to Mendoza's guitar thrusts, which bounced off the windows that looked out over the river. Greg Fox is an American drummer, known for his work in black-metal rock bands like Liturgy. In Monheim, with a quintet he calls Quadrinity+, he played a gorgeous, ethereal, atmospheric jazz concert in billowing soundwaves. Liturgy fans would have been puzzled. The audience on the boat was thrilled.

Robert Landfermann, Monheim Triennale. Photo by Niclas Weber.

Two strong jazz projects were American pianist Kris Davis's Emergence Quartet and German bassist Robert Landfermann's Rhenus. Davis presented a new, multifaceted composition, "Backyard Suite." The slow unfolding of its final movement, "Mourning," held the silent audience rapt. Two impressive young players who had been Davis's students at the Berklee College of Music in Boston made their European debuts: Milena Casado (flugelhorn) and Ivanna Cuesta (drums). Robert Landfermann's excellent septet contained two drummers, a harpist, and Elias Stemeseder, one of the most talented young piano players in Europe.

Sofia Jernberg, Monheim Triennale. Photo by Niclas Weber.

Two of the most anticipated and ambitious Signature Projects were long-form compositions for large ensembles, including strings. The composers were vocalist Sofia Jernberg of Sweden and saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock, originally from Germany, now based in New York. The projects were "Hymns and Laments" and "Dreamt Twice, Twice Dreamt," respectively. Neither composer used strings for their conventional lushness but for spikes of rhythmic energy and startling, edgy sonorities. One of the festival's most mesmerizing moments was Jernberg's interpretation of Duke Ellington's "Come Sunday." It was beyond adagio, so slow that at first it was unrecognizable. Trumpeter Peter Evans and Jernberg barely breathed the melody, as if they were dreaming it separately.

The ship was a wonderful place to listen and hang. During breaks in the music, you could climb up to the top deck and take the air, sip German pils, and watch long barges pass by slowly on the rippling Rhine.

One of my lasting impressions of the Triennale is the contrast between the elegance of the presentation and the rawness and insurrectionary spirit of much of its music. The concerts of guitarist Stian Westerhus and contrabass saxophonist Colin Stetson offered grimy industrial music of the streets in impeccable locations like the MS RheinGalaxie.

A triennale takes place every three years. The next full edition in Monheim will be in 2025. But Michalke has plans for related events in 2023 (a "Sound Art Festival") and 2024 (a "Prequel").

The Triennale was a unique celebration of creativity, but in one respect it was typical of festivals on the European circuit: the beauty of its settings. The places where Europe likes to put music include castle courtyards, monasteries, fortresses, ancient amphitheaters, and medieval town squares. The jazz festival that wrote the book on embedding music into its physical environment is the Südtirol festival. It is based in the far north of Italy, in Bolzano, but it presents concerts all around the South Tyrol region, one of the most beautiful places on earth. The mountainsides are so steep they seem perpendicular. They are in two shades of green: dark for the forests, emerald for the terraced vineyards. Südtirol puts music in meadows at 7000 feet in the silver, serrated Dolomites (reachable only by cable car and a hike), on moonlit rock outcroppings, on ledges in quarries, on trains, and in the gardens of palaces. Südtirol is where I went next.

Francesco Diodati, Joe Rehmer, Lukas Koönig, Reinier Baas, Südtirol Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

For many years, programming has been in the hands of Festival Director Klaus Widmann, who by day is a physician. His bookings tilt strongly left of center. Very few famous musicians play Südtirol, but many of the most exciting emerging jazz artists in Europe show up there. Two examples: Francesco Diodati of Italy and Reinier Baas of the Netherlands, maybe the two best under-40 guitarists in Europe. Diodati is a fearless experimenter who conducts ongoing live research into the variety of sonorities achievable with a guitar played through modern electronics. Baas is more of a jazz-guitar classicist. Both have chops of doom.

tellKujira: Stefano Calderano, Francesco Diodati, Francesco Guerri, Südtirol Jazz Festival. Photo by Tim Dickeson.

I saw Diodati first in Merano, a lovely town 20 miles from Bolzano. He played refined punk jazz, in a park with drummer Stefano Tamborrino. Three days later, he appeared in a morning concert on the leafy grounds of Palais Toggenburg in Bolzano with a band he calls tellKujira, a rarefied string ensemble (two guitars/viola/ cello) that collectively improvises clouds of sound, some fierce with energy, some airy and serene. They have not recorded yet but need to.

- Log in or register to post comments