| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Thanks for that article, so well done!

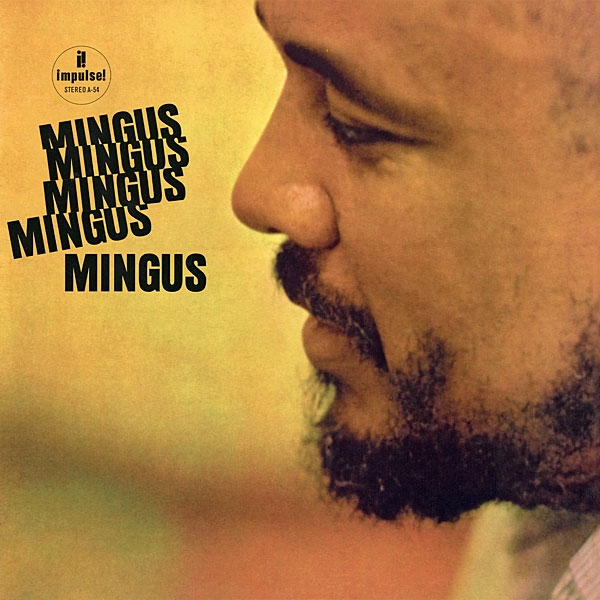

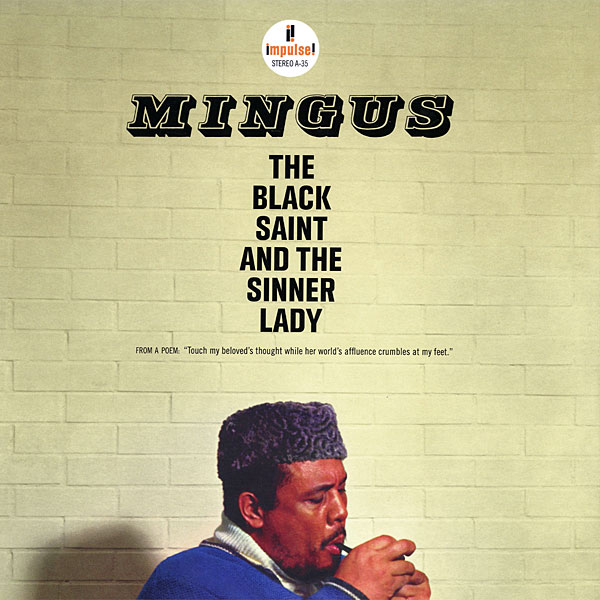

As part of its collaborative series with Chad Kassem's Analogue Productions, the Universal Music Group has released fine vinyl pressings of two classic Mingus albums from the Impulse! Label: Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus and Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. Both feature 11-piece bands, but otherwise they're different: Mingus Mingus consists of variants on six Mingus compositions first played on earlier albums (sometimes under different titles) plus Mingus's bass-heavy cover of Ellington's "Mood Indigo." Black Saint consists entirely of new compositions, which Mingus conceived as a seamless suite for ballet. Remarkably, all of Black Saint and two of the seven tracks on Mingus Mingus were recorded on the same day (January 30, 1963). The rest of Mingus Mingus was recorded the following September.

More remarkable still, both albums are masterpieces. Mingus regarded Black Saint, at the time and also when looking back later, as his best album, and I agree. Like most of Mingus, these two albums are unsuitable for background music; they demand—and, once you give in, rivet—your attention. Especially on Black Saint, the movements flit back and forth between ballads and howls, classical and blues, romance and melancholy, joy and nightmarish anxiety. (This may be the only jazz album with liner notes written by the musician's psychiatrist. They're insightful notes, too.)

Within these movements, the orchestrations are oddly sublime: flute meshing with contrabass trombone, alto and baritone saxophones crooning a duet while a tenor supplies overtones, and drums cascading through tempos that clash, align, or moodily undulate with the music. Mingus pushed his band mates into a style of group improvisation rooted in Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton but also thoroughly modern without being merely derivative: He'd yell at soloists, when they reverted to Charlie Parker riffs, "Stop imitating Bird!" (though Mingus, too, was deeply influenced by Parker). Above all else, this music swoons and swings.

Mingus leapt wild pirouettes off the shoulders he stood on (Morton, Ellington, Parker). Even now, six decades later, it remains novel—yet you can hear his influence in music everywhere.

Mingus developed his styles through the 1950s with small groups he dubbed Jazz Workshops. He fused the styles and expanded the ensembles in the '60s, these two albums being his most raucous experiments. Later, he shifted to ensembles of varying size and personnel, always innovating while staying true to the traditions, a balancing act that few attempted and fewer mastered.

Mingus died of Lou Gehrig's disease in 1979 at the age of 56. Throughout his short lifetime, he recruited and cultivated a cohort of creative musicians—only Ellington, Art Blakey, and Miles Davis rivaled him in spotting and developing talent—and kept them on (through turbulent streaks) as long as he could. The musicians on these two albums include reedmen Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, and Charlie Mariano (whose solos on Black Saint are shiveringly sensuous); trombonist Britt Woodman; and two of his longest and most sympatico companions, pianist Jaki Byard and drummer Dannie Richmond. Like Ellington, he composed parts, or whole compositions, with particular musicians in mind. This is one reason why Ellington or Mingus tribute bands, even when they're competent and impassioned, fall short of the real thing.

The sound quality of the original Impulse! LPs—engineered by Bob Simpson, who recorded several jazz albums for RCA as well—is vibrant, dynamic, and tonally true. A couple of caveats. First, there isn't a seamless soundstage; rather, the instruments seem crowded into three spheres—one group around the left speaker, one group in the center, one group around the right speaker. Second, there's a bit too much reverb. These are qualms, not serious problems. The Analogue Productions reissues, mastered by Ryan K. Smith, come close to the originals, though they seem less present, as if some of the transient peaks had been smoothed over. This too is a small thing, though. These LPs are livelier than previous reissues, vinyl or otherwise.

These are vital, essential works, and the sound quality is more than good enough. Buy the original pressings if you can find them; buy these if you can't.

Thanks for that article, so well done!

and they are fantastic in terms of both sound and packaging, period.

You do a real disservice to the hobby with comments such as “the sound quality is more than good enough. Buy the original pressings if you can find them; buy these if you can't.” GIVE ME A BREAK. This is pure snobbery and elitism. The originals will cost you 10X the price of these stunning reissues. This is the type of nonsense I hate about Stereophile and why I cancelled my subscription long ago.