| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Revinylization #17: Gearbox Records & ERC's Jazz Reissues

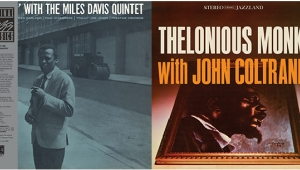

In Revinylization #9, I profusely praised the expensive, unobtanium Electric Recording Company (ERC) stereo reissue of Sonny Rollins's Way Out West. The record was superb-sounding and beautifully made.

"Clearly, these records are valuable in part because they're rare. But only in part. They're also valuable because they're beautifully cut, well-crafted, and gorgeous. I can live with their business model, even if I don't love it. I'm just glad there's a place in the world for objects like this."

I still am—but I'm also still ambivalent about hyperlimited editions such as those issued by ERC. "I wish this experience could be more widely shared," I wrote—"that ERC would press more copies and sell them, maybe, at a lower price."

Most ERC issues are limited, like the Rollins, to 300 copies; only 99 are pressed for some classical releases and boxed sets. Even at £350, most ERC releases sell out within days if not minutes. What if ERC increased the number of records they press to, say, 500 copies instead of 300 for a typical issue? It seems likely that they could sell more records if they pressed more, even if the price remained the same. I asked ERC's Pete Hutchison in an email what factors determine how many copies they press. His answer: Pressing numbers "vary from release to release and there is no set pattern, however some of our contractual obligations only allow a certain quantity."

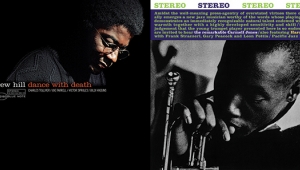

I don't mean to pick on ERC. They are merely a convenient example of the hyperlimited-issue phenomenon. The same questions could be asked about any in-demand limited issue, including, for example, the Music Matters SRX series (although I don't know if that series will continue now that Blue Note is producing its own high-quality, unlimited vinyl reissues. I put the question to the head of Music Matters Jazz, but at press time I hadn't heard back. My guess: The series will continue, but not with Blue Note.).

Why do I care about this? Because I dislike stress and frustration. Severely limited editions create both; you can observe this consumer frustration in Facebook groups and vinyl-focused online discussion forums.

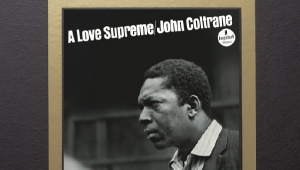

I'd also like to see less secondary-market scalping, another source of consumer frustration. As I write this in late February, there are six copies on Discogs of ERC's most recent issue, Mal Waldron's great-sounding, mono Mal/2, with John Coltrane and an all-star cast. Discogs' prices range from $700, for a copy the listing says has been played once, up to $1149 (plus $5 shipping) for an unopened copy. Alternatives? I couldn't locate a non-ERC vinyl copy currently offered, although a first pressing graded "Excellent" sold February 7 on eBay for $899.

Don't think I'm complaining. We're living in a golden age of vinyl reissues. The only way you could do better would be to go back in time and live through the late '50s and the '60s, into the '70s, with a good record store down the street, hindsight, and plenty of disposable income—then somehow make it back to the 21st century without damaging those records (or yourself ) in your own personal wormhole. Still, I'd be happier if more 2021 vinyl lovers could share the current bounty.

I haven't received many reissues this month, so I'll use my Editor's prerogative and mention a label that does not do reissues but that releases good music in very good sound.

Gearbox Records is based in London. They've been in existence since 2009. You can buy their records on Amazon and in local record stores. They cut their own vinyl in-house on a Haeco Scully lathe driven by Westrex RA1700-series amplifiers and with a Westrex 3DIIA cutting head. Gearbox even employs its own vinyl-mastering and cutting engineer, Caspar Sutton-Jones—who also plays saxophone in London funk band Space Ghetto. The Gearbox facility is so well respected that they do a robust third-party business; records by Brian Ferry, Ronnie Wood, and many others have been mastered and cut there. "We try to approach Van Gelder's sonic signature with our own twist," Gearbox owner Darrell Sheinman, himself a musician, told me in an email. He didn't say what the twist is.

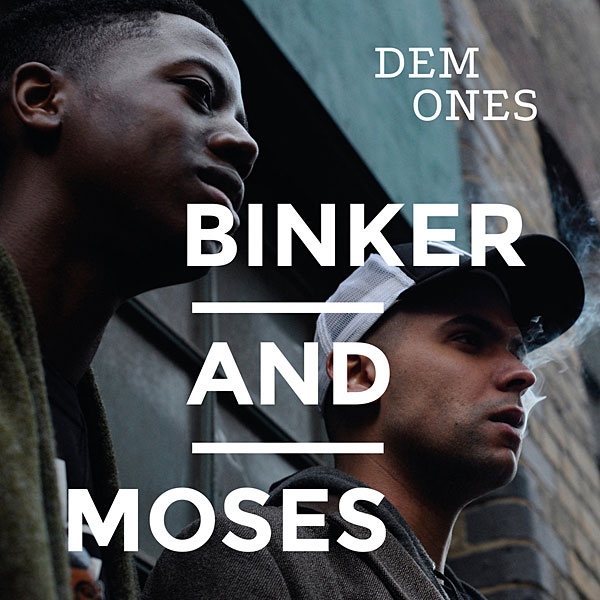

If Gearbox is known for anything, it's for digging through European archives and issuing recordings from major jazz artists that have never been released before, often from broadcast tapes; recent examples include Don Cherry's Cherry Jam and Thelonious Monk's Mønk. Lately I've been enjoying studio recordings by musicians from London's current jazz scene. I've grown fond of Dem Ones by saxophone-plus-drums combo Binker and Moses. (Be careful though: I had a problem with the run-out groove—an oversized center label.) I'm also enjoying Fyah by jazz tuba player Theon Cross; Moses (Boyd) also plays.

These records could hardly be more different. The former is edgy, sparse, improvisational instrumental jazz; the latter is simpler, closer to pop—not ska but, with its simple, repetitive rhythms, it makes me think of ska, deconstructed. Sort of. With tuba. Whatever it is, it's good fun in good sound.

Finally, speaking of non-reissues: By the time this issue is published, Blue Note's reissue-focused Tone Poet series will have released its first non-reissue album, appropriately titled Tone Poem, by Charles Lloyd & The Marvels. "The Marvels" are Bill Frisell on guitar, Greg Leisz on pedal steel, Reuben Rogers on bass, and Eric Harland on drums. I'm looking forward to this one.

- Log in or register to post comments