| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

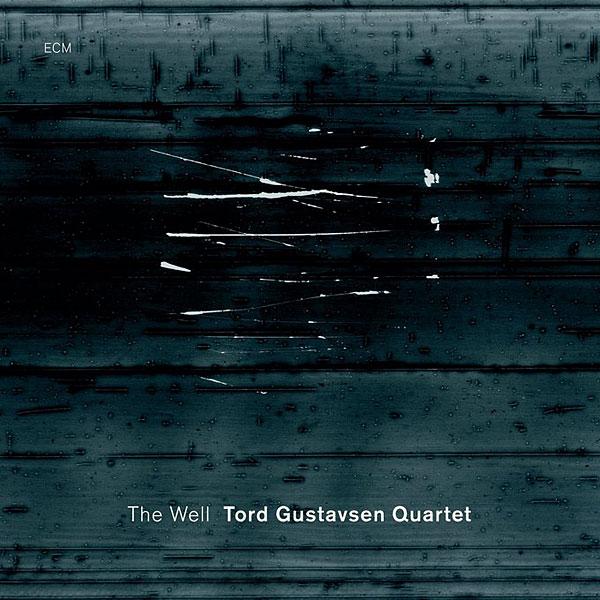

Recording of April 2012: The Well

Tord Gustavsen Quartet: The Well

Tord Gustavsen, piano; Tore Brunborg, tenor saxophone; Mats Eilertsen, bass; Jarle Vespestad, drums

ECM 2237 (CD). 2012. Manfred Eicher, prod.; Jan Erik Kongshaug, eng. DDD. TT: 53:19

Performance *****

Sonics *****

Tord Gustavsen, piano; Tore Brunborg, tenor saxophone; Mats Eilertsen, bass; Jarle Vespestad, drums

ECM 2237 (CD). 2012. Manfred Eicher, prod.; Jan Erik Kongshaug, eng. DDD. TT: 53:19

Performance *****

Sonics *****

The first time I heard J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Klavier, I heard an endless sameness, lovely but undifferentiated. Only over many hearings did each pairing of prelude and fugue begin to emerge from the background, as what Bach did in each iteration of the same received form began to be revealed as an inexhaustible richness of difference. Gradually, I was learning Bach's musical language; only then did I begin to get an idea of what he might be saying.

This process goes even more slowly when the musical form on which changes are rung is not pre-established but invented by the composer-performer. With his very first record, Changing Places (2003), Norwegian jazz pianist Tord Gustavsen, with bassist Mats Eilertsen and drummer Jarle Vespestad, presented a fully developed musical sensibility that the leader has described as "a good balance between continuity and subtle variation," and a compositional style that is "a form of abstract lullabies." The Ground (2004) and Being There (2007), though just as strong in their own rights, were written and played in the language established in Changing Places—the differences between them are much smaller than the difference between the first album and anything else the listener may have heard. To the casual ear, the three discs sound very similar.

But though Gustavsen's music sounds mellifluous, gentle, mellow, and laid-back, it is not created for the casual ear any more than Bach's was. The lullaby is less a form than an intent—to soothe with sound a restive soul—that is difficult to fake. The qualities in Gustavsen's music of affection and respect—for each note, interval, rolling modulation, silence, and fellow player—are perhaps as high as I have heard in improvised music. These lullabies are not for putting the listener to sleep, but to quiet the listener enough to be able to fully hear them. The Well is the opposite of a blowing or cutting session—the emphasis is not on how many notes can be played, or how virtuosically, but on how much music can be made with as few notes as possible. Gustavsen's classical training is audible in his precise articulation; he seems to release each note with reluctance, only when it, or he, is ready. The music sounds no less spontaneous for seeming almost through-composed. The players do not impose themselves on listener or rhythm. Instead, one feels invited to an intimate musical séance in which the music is revealed in utter nakedness, with no hint of exhibitionism.

For his fourth album, Restored, Returned (2010), Gustavsen added a tenor-sax player. When I heard that, my heart sank. I could imagine no tenor player sensitive enough to join hands in a Gustavsen séance. But on that album and now on The Well, Tore Brunborg is a marvel—a clean, cool player in the mold of fellow Norwegian Jan Garbarek, but without Garbarek's genuinely heroic scale. Brunborg plays the tenor more quietly, sensitively, delicately than I had thought possible, and is thus a perfect match for this trio; his voice is, more often than not, the leading one, though that lead sounds less taken than given.

I would not be without one of these 11 tracks. The longest, "Suite," is an urbane lament of such sophisticated sorrow that its tone approaches the tragic; any other sax player would blow twice as loud here. Gustavsen follows Brunborg's solo with one of his own, in a muted hard-bop tenderness that seamlessly returns to the head's leaping intervals, a Gustavsen trademark. "Circling" may be the world's slowest gospel tune. It is extremely difficult to play this well this slowly this quietly, the rhythm seeming to pulse under the players' fingers like the heart of a sleeping child. The constantly modulating, ever-resolving chromaticism of "Communion" is reminiscent of a Bruckner Adagio, with just as glowing a nimbus of the sacred. Later, in "Communion, var.," the players merely hint at the same changes, seeming to hover, almost static, over each chord, keeping the music aloft with the merest flicks of stick and key, finger and reed. In "On Every Corner," Brunborg's sad, sexy sax seems to tell the short story of a tender heart's breaking. "Intuition" is an aria for countertenor sax, and in the title track's modal high Orientalism—a mode that reappears throughout The Well—Brunborg's quiet authority in the snakily sinuous melody is absolute, each note and inflection inevitable as fate.

Like the music, the sound has me blithering oxymorons. The sense of space is cool and warm at once, vast and intimate. The sea-moans of Eilertsen's bowed bass echo in a great solitude, and Vespestad's drumming is often so delicate I wasn't always sure what I was hearing: the creak of his stool, or a muted snare barely tapped? A rolled cymbal rises from and descends back into silence like the long, slow breath of, again, someone deep in sleep. Abstract lullabies, indeed. I can't imagine ever getting to the bottom of The Well's noble music, so exquisitely recorded. Toss down your bucket and drink.—Richard Lehnert

- Log in or register to post comments