| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

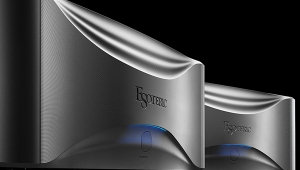

PS Audio HCA-2 power amplifier Page 2

Paul phoned me about two such products: the Model 8.0 preamp (which should be available by the time this article appears), and the solid-state, switch-mode HCA-2 two-channel amplifier, which has been available for several months. The HCA-2 retails for $1695; Paul expects the preamp to come in at about the same price.

"I know you love tubes," Paul said. "You'll flip over the HCA-2."

"Why didn't you make a tube amp?" I shot back.

"Funky devices," replied Paul. "Anyway, as you know, transistors are valves, too. They turn the power-supply voltage up and down in direct relation to the musical signal. They are switching devices—or valves."

Transistors itch to switch. I always get a good lesson in electronics when I talk with Paul.

The HCA-2 is a class-D power amplifier, although, since D is for dummies and class-D amps have not had the greatest reputation for sound, PS Audio calls it a "hybrid class-A" amp. Class-A refers to the input stage. Usually, when an amplifier is described as "class-A," "class-A/B," or "class-B," what's being referred to is the bias state of its output stage. Paul explained:

"When you refer to different classes of amplifier, you're talking about how much the output transistors are on when there is no music. In a class-B amp, the output stage produces no current except in response to a signal—that is, the music. However, no one uses class-B because of the nasties, or distortion, that occurs at the zero crossing point, where voltage switches from negative to positive polarity, or vice versa. You get a big bump—or notch."

"So you try to nix that notch?"

"Yes. You run some constant current—current that doesn't turn on and off in response to the music. Class-A is constant current, and in the real world of amplifier design, 'class-A' tends to be relative. The more constant current you have running through the output stage, the more an amp is class-A."

True class-A amplifiers are usually very large, run extremely hot, consume gobs of electricity, and, ultimately, tend to burn themselves up.

"Even class-B is not ideal," Paul continued. "That's when you have essentially two valves, and they could be tube or transistor—a plus valve and a minus valve. As these go up and down, plus and minus, they regulate how much of the power-supply voltage gets out to the speaker in response to the musical signal.

"However, even class-B generates a considerable amount of heat. A tube or transistor emits heat according to how much voltage is placed across the device. Vary the voltage and you produce heat."

In other words, it's the in-between state that produces the heat, not just the voltage itself.

Paul himself was just getting warmed up.

"Imagine a water faucet. You have a big water supply on the input side and you have usually a smaller amount of water flowing through the output side. It doesn't work this way with a garden hose, but electronically, the amount of current going through the faucet relative to the amount of current in the water mains creates heat. The more water that travels through the faucet, the more heat you create.

"If the faucet is off and you have no water traveling through it, you generate no heat. But here's what's interesting. If you turn the faucet all the way on, there isn't any heat, either, because the same flow that's available at the input is delivered to the output.

"On or off is good. It's the in-between states that create heat. This is why we have massive heatsinks in both tube amps and transistor amps, to dissipate the energy.

"With a class-D amplifier, the water—the current—is either on or off. There is no in-between, except for the quick transition to get from zero to the 'on' state. So a class-D amplifier generates almost no heat. It either delivers none of the current available from the power supply or all of it.

"Output transistors are happy about this, because, like tubes, they're valves, or switching devices. They love to turn all the way on or all the way off. They are far less happy about any state in between, and they generate heat in protest."

The key to good sound in a digital switching amplifier is getting it to switch fast, Paul told me. The HCA-2 switches on and off at 500kHz, or 500,000 times per second, which is so fast that you perceive the sound as continuous. The output transistors are MOSFETs, two pairs per channel.

- Log in or register to post comments