| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Poem: Stereophile Cuts an LP The Musicians

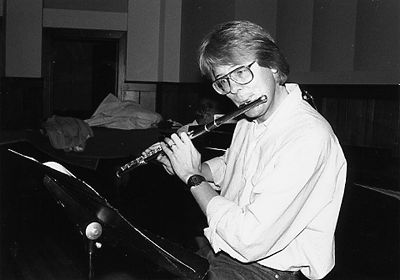

The Musicians: Richard Lehnert

The Flutist: Gary Woodward, first a student at USC, where he got his Master's Degree in the flute, has now been teaching flute there for five years. During a break in the recording sessions, Gary and I sat down while JA was carrying out some urgent repair work on one of the tube microphones and talked about how long he had been gigging professionally.

Gary Woodward: My first professional job here in Los Angeles was in 1976, in a Broadway show called Baker's Wife. I did the American Ballet Theater that year as well. That kind of got me started. Now I do quite a bit of chamber music work, and play in the Glendale Symphony. And I play in various theater orchestras—Music Center Opera, different ballet companies that come through town, and Broadway shows. I've been working this past year on Les Misérables, at the Schubert Theater; that's been quite an extended project!

Richard Lehnert: Have you done other recordings?

Woodward: This is my first solo recording. I'm really excited about it. I've done quite a bit of studio work, but, of course, that's a different thing. This has been my busiest year, which has been exciting. What's kept me the most busy in the studios this year is the ABC maxiseries—30 hours of television!—War and Remembrance. It took the better part of a year to score that—65 people in the orchestra, which is a rarity these days. There was a whole bank of electronics there as well. I had some nice bass flute solos, so it was fun.

Lehnert: Have you noticed any differences between what we're doing and other sessions you've done?

Woodward: I'm really struck by the clarity of Kavi's tube microphones. I've never heard anything as realistic as that, and I've played all the major studios in Los Angeles, which have the very, very finest equipment! Usually, you go in to hear a playback and you think, well, that's close. That gets most of what I'm trying to do with a particular solo or passage. And sometimes you go in and you're shocked with the sound that they think is right, what they think a flute sounds like—this buzzy, bright, edgy sound. To my ear, it sounds nothing like a flute.

Lehnert: And yet that's the sound of choice for many commercial recorders.

Woodward: I wonder why. Because that's the direction that flutes themselves are going as well. The sound of the actual instrument, the modern flute, has a very bright tone. They've made so-called improvements to the embouchure and lip plate that do help some of the flute's inherent problems in the lower registers: difficulties in playing full, and in articulation. But the tradeoff is this sound that, to my ear, is more like a trombone than a flute.

Lehnert: And they're consistently designing instruments that will play louder.

Woodward: There's that, too. There is some question, though, as to whether these flutes that sound loud up close will project. It seems to me that the sound stays loud very close and doesn't really project to the back of the hall.

Lehnert: Part of what you hear in studio playbacks is probably the fact that a studio isn't a real hall, and anything that will make it sound like a real hall has to be added...

Woodward: Exactly. But there are a couple of studios in town that sound very, very good as halls, the studios at 20th Century Fox and MGM especially.

Lehnert: Film-studio soundstages?

Woodward: Huge, wooden rooms. They sound very good. But even then, sometimes the engineers will hang up a microphone, and the recorded sound is disappointing. But what we're doing here today is just amazing—it's almost too honest!

Lehnert: That was one of the problems with early digital recordings—no one knew how to do it at the beginning. Everyone was used to relatively close microphone placement, and you can't do that with digital recordings because you get all sorts of things you wouldn't want to hear: players breathing, pages turning, conductors humming along, chairs creaking, everything. You have to learn to pull back a bit. What strikes me, listening through the headphones, is how much richer the tube mikes are; I hear that primarily with the piano sound. It's such a full, large sound, without overpowering the flute.

Woodward: Right. And the thing that I strive to get in my playing is a richness and fullness of the flute tone. So often that is lost in the recording, and all you get is the top end of the flute.

Lehnert: Can you hear that here?

Woodward: Oh, yeah. It's very nice to have that come through.

Lehnert: How about comparisons with the solid-state mics we've had to use?

Woodward: The solid-state mics are still some of the best I've heard. They capture much of what I'm trying to do, but I'm still sorry we've had these problems; the tube mics were really exciting.

Lehnert: Well, John is resoldering one of them right now. Is that an alto flute you're playing today?

Woodward: Yes, in the middle part of the Reinecke, he asks that it be played that way, on violin or clarinet. It's not in the flute part at all. I'm not sure why.

Lehnert: I've heard that your principal flute is made of platinum, of which there are very few.

Woodward: Right. I'll be using that flute on some of this recording, I hope. It's made by Verne Powell, and, from information I've been able to gather, Powell himself made only seven of them. This one was made originally for John Wummer, the principal flutist of the New York Philharmonic at the time. He played it in the Philharmonic, and also, I believe, in the NBC Symphony. In my mind, Powell epitomized flute makers—he was uncompromising in his craftsmanship. I think they're the finest instruments that have been made.

- Log in or register to post comments