| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Nordost Heimdall interconnect & speaker cable Page 2

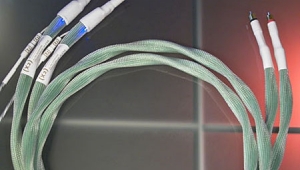

Also during those three years, my main interconnect has been a borrowed 6m pair of Nordost Valhallas: the best-sounding long interconnect I've used. Thus, substituting an identical length of the Heimdall interconnect seemed a pretty fair review comparison, the only other difference being the upgrade to those fancy WBT phono plugs. I used 1m and 1.5m samples of the Heimdall interconnect for my source components. The speaker cables reviewed were 2m Heimdalls, with spades on the source end to suit my Lamm monoblocks, and the excellent Nordost Z-Plugs (a number of which I bought years ago for installing on my other cables) at the loudspeaker end.

Footnote 3: Not to be confused with the more famous—and arguably more well played, especially by the cellist—Heifetz-Feuermann recording of 1939.— Art Dudley

Listening

Over the past several weeks I've listened to the new Nordost products in various combinations: sometimes just the speaker cables, with all my usual interconnects in place; sometimes just one interconnect pair at a time, in combination with all the other usual cables; and sometimes—in fact, most of the time—the whole Heimdall pantheon, all at once.

To begin with the latter, the Heimdall cable system was beautifully listenable, and very much in keeping with the qualities that the Nordost Valhallas have led me to expect. The Heimdalls were as uncolored, as tonally neutral, as any other wires I've heard, and did nothing to detract from the qualities I prize in the components I've bought over the years. With the Heimdalls, my music system breathed naturally: There were no constrictions, no sense of the music being squeezed out, strained out, or shot out at me. The Heimdall system was natural, easy, and wide open.

As to individual cable applications, my experience told me that the Heimdall interconnect, in generous lengths and used between preamp and power amps, is the family's biggest bargain. After weeks of switching back and forth between the 6m Valhalla interconnect and the 6m Heimdall, I'm still not sure I can reliably hear more than the most ephemeral difference, if any, between them.

An example: On a brilliant new Cisco Music LP of the Heifetz-Piatigorsky recording of the Brahms Double Concerto, Op.102 (LDS-2513, footnote 3), Piatigorsky's "Batta" Stradivari cello was right there in virtually every sense of realism: spatial, timbral, and textural, as well as sheer size and scale. That was true with both of the Nordost Micro Mono-Filament cable lines—well beyond everything else I have in-house.

But of all the areas in which the performance of the long Heimdall interconnects matched that of the long Valhallas, perhaps the most pleasing was the fact that, with these budget cables in place, my system's sense of presence wasn't diminished one whit. Until now, the Valhallas had been supreme in that sense.

Differences between the speaker cables struck me as more distinct: Going from the Heimdalls to the Valhallas was like turning the Music knob clockwise: The Heimdalls gave me a lot, the Valhallas even more.

I actively dislike such things as trying to "hear into the stage"; real though those sonic effects may be, they usually distract my attention from the meaning of the music, which is what I'd much rather focus on. That said, and knowing that I'm paid to do more than just have a nice time, it's my duty to say that there was an audible difference between the Valhalla and Heimdall speaker cables in the way that my system let me, er, hear into, um, things. Like stages. Only with the Valhalla speaker cables in place could I hear precisely what the horns and the back-row percussionists were doing in recordings such as a typically fine Speakers Corner reissue of Ruggiero Ricci performing Saint-Saëns' Havanaise, Op.83, and Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op.28 (LP, Decca/Speakers Corner SXL 2197).

Beyond that and the addition of a bit of artificial texture—itself the most obvious and audible difference, I thought—the less expensive cable was a close second, and was downright brilliant in its own right. With recording after recording it did seemingly everything well, with a conspicuously wide frequency range and apparent freedom from colorations of any sort. I'm sadly unqualified to comment on the cable's image-location performance, afflicted as I am with a seemingly incurable case of don't-give-a-shit-itis when it comes to that and other effects that some hobbyists obsess over so. Suffice it to say that I was completely satisfied.

I should add that I continued to prefer the Audio Note AN-Vx interconnect as a source to preamp cord—the only application to which the 1.5m pair I own can be reasonably put, in any event. The Audio Note was no less thrilling in its portrayal of the great, manic clatter of "Old Joe Clark," as played simultaneously by eight bluegrass mandolin stylists on Bluegrass Mandolin Extravaganza (CD, Acoustic Disc ACD-35), yet no other cable has matched its dynamic abilities in my system: The Audio Note was better than both the short Heimdall and the short Valhalla at signaling very tiny but musically important changes in dynamics.

Conclusions

Did you know that the Christian Hammer Stradivari violin (1707) just sold for $3.5 million? A year before that, the Lady Tennant Stradivari (1699) went for $2 million. And it's just a matter of time before the Lady Blunt Strad (1721) will come on the market: the only one left that, as far as anyone knows, still has all of its original neck. Most people in the vintage-instrument field believe the Lady Blunt will fetch between $5 and $8 million—or more.

Those instruments are prized not only for their rarity, but because they sound better—leagues, worlds better—than any others. The likeliest reason for that is Antonio Stradivari's proprietary varnish: a microscopically thin layer of spirit gum and insect husks and God knows what else, the precise formula for which is now lost to us.

Half the world's woodies could spend their lives analyzing a sliver of that finish and not find an iota of difference between it and the stuff that's used today on a $90 Chinese fiddle; the other half would refuse the assignment, swearing that the varnish couldn't possibly affect the sound.

But anyone who's ever played a Strad or heard one up close knows that the woodies are wrong—dead wrong, stupid wrong—which only goes to show how incomplete our knowledge remains with regard to why things sound the way they do. In fact, when you get right down to it, we know nothing at all. Nothing. At. All.

The Nordost Heimdalls? Here's the Cliff Notes version, the quick, easy paragraph I'd send to a friend: I tend to like Nordost cables in general, and the Heimdalls are no exception. They sound clear and wonderful, and almost as good to me as the Valhallas. Whether that's a direct consequence of the technology Nordost propounds—and at least some of which sounds convincing to me—or whether it's just a lucky combination of this amp with that wire, is anyone's guess. Caveat whatemptor.

But there's no question in my mind that the Heimdall interconnect and speaker cables are worth every penny, and then some, of their still-not-inconsiderable prices—in which sense, I suppose it really is possible for a four-figure cable to be considered a "budget" product.

Footnote 3: Not to be confused with the more famous—and arguably more well played, especially by the cellist—Heifetz-Feuermann recording of 1939.— Art Dudley

- Log in or register to post comments