| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Murray Head: Nigel Lives Again Page 2

Primarily tracked in June 1972 in Studio Two of Olympic Studios, in southwest London, on a 16-track machine, Nigel Lived is famous among audiophiles for its many live recordings made outside the studio. For the track "Religion," a male choir was recorded in St. Paul's Church, Covent Garden, using Pye Studios' 16-track mobile unit and four Neumann U87 microphones. While they were there, the church's pipe organ was recorded for use in "Pity the Poor Consumer."

Between 3 and 5am the next morning, again using the Pye truck and the Neumann mikes, saxophonist Chris Mercer was recorded in the Tube, under the Centre Point building, for "Dole." More recording at Olympic ensued, and by August the album was ready to be mixed. That took another 14 days. In his book, Brown diplomatically wrote, "The tracks were very involved and hard to mix manually."

"Tracking and mixing went pretty fast," Brown told me. "Basic tracks were a five-piece band playing together. Overdubbing consumed the most time. We were working with 16 tracks, so we had to think ahead. You couldn't do everything individually and keep layering up. It's a combination of instruments, and putting things through Leslie speakers, and messing things up with our limited amount of technology at the time, that made it such a really exciting project to work on. Everyone who worked on it got caught up in this enthusiasm. And that's the first time, and I think probably the only time, that I recorded the electric harp!"

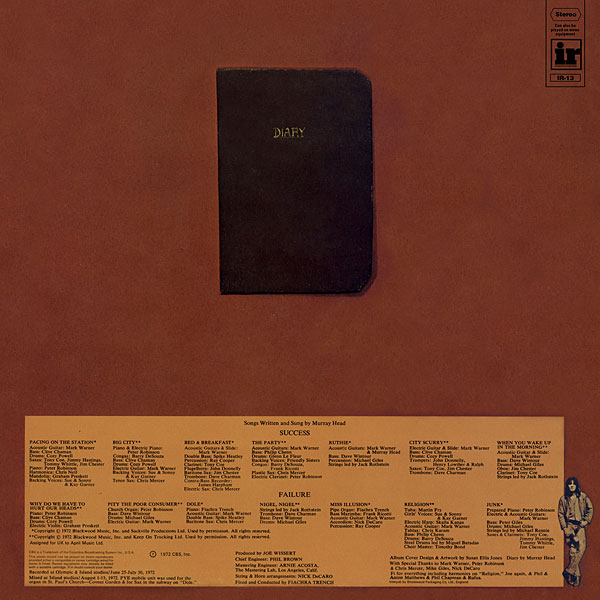

One of Head's favorite stories about the album concerns its cover art. When Clive Davis called him to say that the artwork was too expensive and would have to be changed, Head offered to drop points on the album if the original artwork was used. Davis was so stunned by the offer—which he accepted—that he wrote about it in his autobiography, The Soundtrack of My Life.

"When John Hammond came over and listened to it," Head told me, "he immediately said, 'It's overindulgent.' I think what he meant was it was going to be hard to explain to the commercial people what I'd done."

Nigel Lived hit the market in 1973 with a resounding thud. "They put it out for five seconds," Head said. "They couldn't find a genre. They didn't know what to call it. In those days, they had only just thought of the term rock opera, which it wasn't, really. It was what you call a concept album, which is what they called Tommy. And I thought, if Tommy stood a chance, then surely this should.

"Critics said I was a renaissance man. That was nice, and I felt honored, but then the first royalties sheets I got from CBS said it had sold nine copies. I think that must be a physical impossibility, but maybe it was their way of saying 'It ain't gonna happen'."

The proof that it sold a lot more than nine copies lies in the fact that Nigel Lived has never been a crazy-expensive item to find and buy on Internet LP sites like Discogs and eBay.

While in any discussion of sound I tend toward the original pressing, in A/B comparisons with my original copies (I have more than one) Intervention's new 45rpm pressing sounds superb.

"Stunning!" Brown said. "It's kept all the romance. It's as close to hearing the master tapes as you can get." He speculated about why the album flopped. "Sometimes, projects like that don't happen in their time, as it were. Murray kind of joked afterwards that we were either five years too late or six years too early. I always loved the album. I just thought it was amazing, regardless of whether it has been successful or not. I played it for a lot of people and I made lots of copies of it. And for years afterward, when I was working with other people, I'd kind of give them a copy—'You've probably never heard this, but check this out.'"

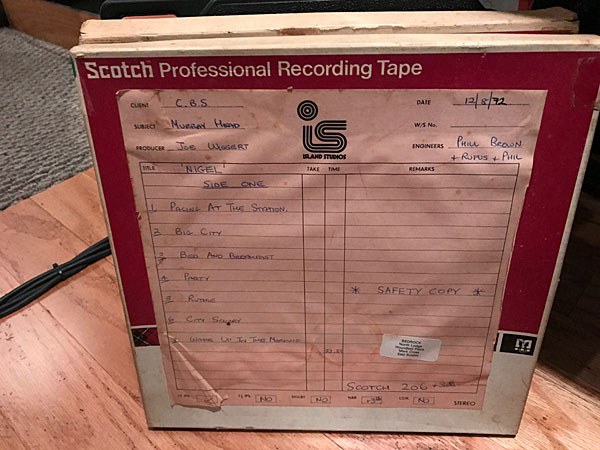

Amazingly, through happenstance more than anything else, the original tapes of Nigel Lived survived, and have been properly stored ever since the album was made. Over the years, Head occasionally visited the CBS's storage facility, on Whitfield Street in London, to make sure they were still there. "A miracle they weren't chucked," he said.

Shane Buettner, founder and owner of Intervention Records, first heard about Nigel Lived several years ago, when Stereophile's editor, John Atkinson, mentioned Brown's book to him. Buettner read it, and was intrigued by the chapter on Head's album. After buying a copy of the original pressing on Discogs.com, Buettner used Facebook to track down Brown, who put him in touch with Head.

Brown shipped Buettner his own personal ¼", 15ips safety copies of the original master tape. "They were magic," Buettner said. "Kevin [Gray, who cut the LP lacquers for the new edition] didn't know the music at all, but he totally responded to it. Every few minutes, he kept saying, 'Why doesn't everything sound like this?' My plan from the beginning was to get a full 45rpm cut with no sonic compromises at all. I think it works for the material, too. Having 'Religion' and 'Junk' close out the record on the fourth side of a 45 set, I just think it's perfect."

Head, who during our conversation was a witty, self-deprecating delight, is delighted to see Nigel Lived back on the market. Despite releasing many more solo albums since, it's clear that he's still stung by the immediate and unceremonious flameout of his debut.

"The other thing that I didn't find out until fucking years later was that there's no such name in America!" His voice squeaked in amused incredulity. "No one's called Nigel. Murray—which is quite a rare name in England—there are thousands of Murrays, millions of Murrays in America. But Nigel? No. They might have finally got a bit of headway [in 1979], when XTC came out with 'Making Plans for Nigel'."

Despite the album's fate, Head can still summon traces of the urgency and excitement that must have accompanied the making of this lost classic. "There were moments, like when we needed two drummers on a track and I said, 'Well look, if we do it at 30ips and we run two Studers together, we can sync them up!' And Phill said, 'You can't do that, it's impossible—they'll never be in sync!' I said, 'It will be in sync enough—don't worry, it will be great.' We did things that no one had ever done before.

"When Phill suggested the same thing to Stevie Winwood, Stevie said, 'Ahh, that wouldn't work, it's impossible.' I was lucky to get Phill Brown really early in his life, and he was as gung-ho as I was at the time. We were both, like, 'Fuck it, let's go for it!' And in a way, thank God we did. In another way, it's sad, because I think I could have offered a hell of a lot more since, but because of the fate of Nigel, that was it—I never tried to be clever again."

- Log in or register to post comments