| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I'm afraid it isn't.

Can we recall the drubbing all digital has been getting until just recently ?

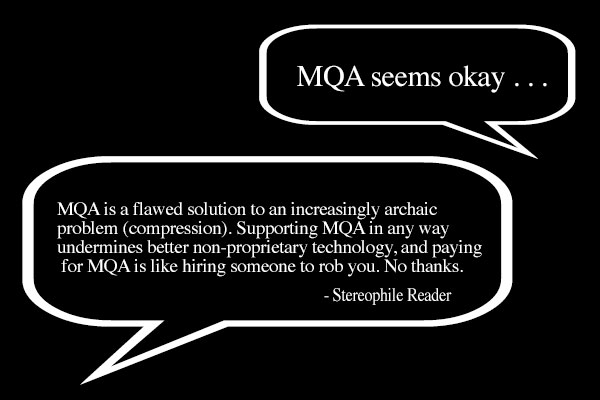

As far as "anonymous" commenters are concerned, we should include the Acid Spitting from Stereophile's Analog Turntable Set-up guru, including the ugly insult he sent me in a ( blocked response ) email.

However, ugliness is not at all a common feature of Stereophile's Vast Readership.! We should acknowledge the high ideals and standards of propriety belonging to the vast group of those composing Journalism or commentary.

Unfortunately, the nightly news is filled with ugliness seeping out Washington (lately), setting a horrible example for the nation to follow. We might have to tolerate it but we don't have to accept it. The option of silencing ugliness is UnAmerican, we have the Constitution for gods sake!!

I've admired J.Atkinson since the 1980s in England, he and Stereophile ( under his... ) remains worthy.

Meridian has been brilliant for a lonnnnnnnnnng time, I'm happy to see B.Stuart finally hit one outa the Park. In fact I'll buy another entire Meridian System ( I've owned 3, so far ), probably the DSP33 & the matching control electronics.

Everybody's talking about MQA, phew, who could've guessed that Meridian would achieve "Center Stage" here in the States?

Congratulations are in order.

21st Century Tony in Michigan