| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

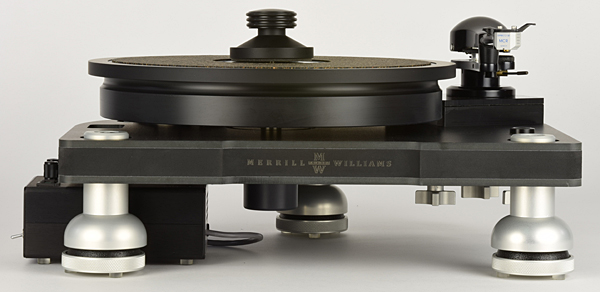

This caught my eye: I found that records were difficult to lift off of the platter, partly because the spindle seems very slightly larger than usual in diameter, and partly because my fingers found it difficult to get a purchase on the edge of the disc—this would be greatly eased by the platter's being a little smaller or a little larger in diameter."

Thanks for mentioning something like that, I fear it would disgruntle me over time.