| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

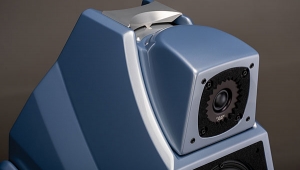

MBL 111 loudspeaker Page 2

When you hear this work live, the spatial presentation reinforces the enveloping tonal ambiguity. The spatial smearing of lesser speakers would interfere with the effectiveness of Holst's almost fetishistic scoring. By contrast, the combination of superb tonal accuracy and secure spatial accuracy offered by the MBLs allows the listener to appreciate the experience in a manner similar to the live event: Themes and accompanying figures restlessly shift in space as they move from one choir of instruments to another, but the listener can clearly hear what is happening and, more important, why.

The MBLs' soundstaging featured excellent image depth, with what appeared to be astonishing transparency. With Stereophile's live recording from the 1995 and 1996 Santa Fe Chamber Music Festivals, for example (Serenade, STPH009-2), the reflections of Julie Landsman's horn from the acoustic shell at the rear of the stage were more audible than I had experienced before. The delineation between the instruments at the front of the St. Francis Auditorium stage and those at the back was also more clear than I have heard it on front-firing speakers.

Some writers hold that this aspect of soundstaging performance, which omnidirectional speakers share with dipolars, is in fact an aberration. The presence of strong, early room reflections, they say, exaggerates the depth cues present in recordings, due to the Precedence Effect. Well, that may or may not be true. But once you've heard the soundstage depth produced by something like a pair of these MBLs, you don't want to give it up. It just sounds more real, is all.

Conventional wisdom has it that German speakers tend to be bright. This was certainly true for a generation of forward-radiating designs some years back which were optimized for flat in-room power response. (Because almost all of a conventional speaker's high frequencies are radiated to the front, you have to tip up its on-axis frequency response to an alarming extent in order to flatten the power response.) With their true omnidirectional design, this should not be true of the MBLs. Indeed, I found them to be remarkably uncolored. The high frequencies, in particular, were not at all bright. Instead, they sounded both neutrally balanced and very clean, lacking any suggestion of fizzy sibilants or steely coloration. Other than the slightly rolled-off nature of its top octave, the degree of which will be room-dependent, this Radialstrahler is one of the best tweeters I have experienced.

The MBL's midrange, especially with the superb little Pass Labs amplifier, was sweet, sweet, sweet. Voices were reproduced with the differences between their individual tonal qualities maximized—always a good sign. A speaker with significant midrange colorations adds an always-the-same formant structure to recorded voices that tends to diminish the differences between their characters. And even though there was not a trace of metallic coloration audible, the German speaker still got what J. Gordon Holt terms the "brassy blattiness" of trumpets and trombones right.

Only in the bass did I find the speaker to have a character that could get in the way of the music. The bandpass-loaded woofer, while offering excellent extension—the 20Hz 1/3-octave band on Stereophile's Test CD 3 was down just a few dB—always seemed a little "slow" compared with the rest of the audio band. Changing amplifiers affected this significantly, the big Audio Research tube amp taking charge of the bass in a way the 30Wpc Pass Labs couldn't match. And using spikes to couple the woofer cabinet to the floor beneath the rug was mandatory. Without them, the bass significantly lacked definition.

It wasn't a matter of poor integration with the moving-coil midrange unit—the transition between all the drive-units was seamless—but the MBL's rich, generous character seemed to lag a bit with music rich in low-frequency transient information, such as kickdrum and bass guitar.

This was never a problem on most classical music. In fact, the lushness and evenness of the MBL's low frequencies added considerably to the music's authority. When the deep organ pedals double the double-bass line in "Saturn" in the BBC Philharmonic Planets mentioned earlier, for example, it was as though the floor of my listening room had suddenly opened up into a huge space. And orchestral double basses in particular had tremendous weight, to the music's benefit. But with jazz, the weight too easily turned to bloat. Stanley Clarke's upfront-miked double bass on "Never Mind," the B&W Music cut from Airto Moreira on Test CD 3, for example, was just too—I really can't avoid the word—"puddingy" (as in extra suet on the side). My wife was in the next room while I was playing this cut with the speakers driven by the Aleph 3: "What speakers are those?" she yelled. "They have too much bass!" She was right.

But if powerfully recorded jazz bass and the four-in-the-bar kickdrum and Fender bass of, for example, my beloved ZZ Top singles CD brought out the worst of the MBL's bass, classical piano recordings brought out the best. Whether it was Robert Silverman performing Liszt for Stereophile (Sonata, STPH008-2), Valentina Lisitsa performing Liszt and Rachmaninoff for Audiofon and Peter McGrath (Virtuoso Valentina, Vol.2, Audiofon CD72070), Hyperion Knight pounding the HDCD-encoded keys (The Magnificent Steinway, Golden String GSCD 031), or even a CD of mono Arturo Michelangeli 78rpm transcriptions (Musical Heritage Society 513996F), which I bought for his astonishing 1948 Abbey Road performance of the Bach Chaconne, the lack of coloration, the powerful low frequencies, and the stable, well-defined imaging allowed the sound of each instrument—but, more important, the music—to communicate with maximum authority.

Dynamically, the MBLs offered excellent contrast. However, their low sensitivity means that they really need more power than I had available to come alive. I didn't have access to the 300Wpc Mark Levinson No.333 (which I reviewed recently) at the same time as the MBLs, and the 100Wpc Audio Research ran out of steam on peaks. Stereophile's Liszt Sonata CD really does require to be played at realistic levels to get the full impact from the 9' Steinway D, yet the VT100, using its 4 ohm taps, was clipping at a sound pressure level of just 88dB, equivalent to about 91dB at sea level. Of the amplifiers I did have access to, the long-discontinued Krell KSA-250 in the Stereophile listening room gave the best combination of loudness and bass definition. I suspect that something like the Krell Full Power Balanced 600 amplifier (reviewed by Martin Colloms elsewhere in this issue) would really make the MBL 111 sing. It would also take tight control of the rather flabby low frequencies.

Summing Up

The crunch time for a reviewer is when the product under test finally leaves his listening room. Is he glad to be rid of it? Or is the parting an emotional wrench? I'm writing this conclusion at 7am, frantically piling CD after CD on the Levinson, playing a cut here, a cut there, to get one last hit of the special things the MBL 111s do before Stereophile's David Hendrick arrives to take the speakers to the photography studio for this month's cover shoot. Its low frequencies may be puddingy, but I fell in love with this speaker's sweet, detailed midrange, clean, transparent high frequencies, grand, sweeping soundstaging, and, above all, the majesty with which it presented much of the music I love. It also demonstrates some remarkably effective and well-thought-out loudspeaker engineering.

If you prefer classical music to rock, have a reasonably large room (which will work better with the speaker's bass than the relatively small rooms I used), don't mind its idiosyncratic looks, and can afford to match this speaker with the caliber of amplifier it requires, then I highly recommend the MBL 111. It is a Class A contender.

- Log in or register to post comments