| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I owned a '66 E-type for 20 years, but my dream car was always the MkII coupe.

But imagine if Jaguar still made a 3.4-liter Mk.II, outwardly identical to the Mk.II of the late 1950s, complete with nonmetallic cream-colored paint and red leather seats, but updated with fuel injection, ABS brakes, airbags all around, and a six-speed gearbox made somewhere other than Coventry. (Untergruppenbach comes to mind.) You'd have to hide your valuables, because I would break the law to buy one.

And that—the car, not the crime spree—is precisely what the Ortofon company of today has managed to do, albeit on a smaller scale: Most of the products in their hi-fi line are decidedly modern, yet Ortofon has never ceased making subtly updated versions of their classic and altogether characterful SPU pickups. As Ortofon itself is fond of saying, "No other company has ever retained a phono cartridge model in their product line for so many years."

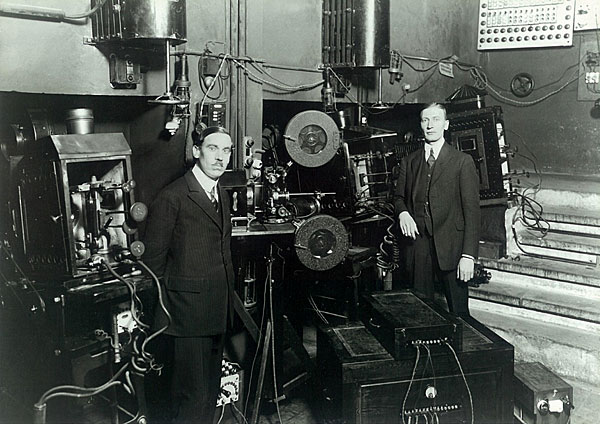

They ought to know: Copenhagen-based Ortofon was founded in 1918 (as Fonofilm Industri A/S), which makes it the oldest surviving manufacturer of domestic audio gear (footnote 1). Following the introduction of their first moving-coil cutter head (the very first one was made for Columbia/EMI by Alan Blumlein, Herbert Holman, and Henry Clark), Ortofon's domestic offerings began in 1948, with their Type A pickups and variants: monophonic moving-coil cartridges in a choice of black (Bakelite) or cream (thermoplastic) headshells with specs that included relatively high output voltage, high impedance, and low compliance, the latter owing to a stiff, shoehorn-shaped cantilever that was riveted in place. A short time later there came the Ortofon Type C pickup: virtually identical to the A, but with a stairstep-shaped cantilever that made possible a more compliant suspension—and tracking forces ranging as unimaginably low as 3gm (footnote 2).

The first SPU (for stereo pickup) followed in 1958. Designed primarily by the late Robert Gudmansen, Ortofon's two-channel MC cartridge featured a shorter, simpler aluminum cantilever, and achieved a significant reduction in moving mass through the use of smaller coils made with fewer turns of wire. Consequently, the SPU produced considerably less signal voltage than its mono predecessors—a characteristic that was addressed by the subsequent introduction of Ortofon's longer Style G headshell, offering room for a pair of miniature step-up transformers. (The very first production SPUs were built into the same short headshells as the Type A pickup; that headshell size, which endured in the Ortofon product line though 2008, thus became known as Style A.)

The Ortofon SPU was an immediate success, and more: In the years following its introduction, while Robert Gudmansen and other Ortofon engineers designed newer and ostensibly better cartridge types with gains in trackability, linearity, and suchlike, consumer demand for the SPU never went away. Some years were leaner for the line than others, but there always remained a core of audio consumers, especially in Japan, who would settle for nothing other than an Ortofon SPU.

Ortofon responded by never turning their backs on the faithful. First, they've continued to manufacture the Ortofon SPU Classic N ($828), which is commendably close in spec to the motor of a 1958 SPU: a low-compliance cartridge with an 18µm-radius spherical stylus and an internal resistance of 6 ohms. The Classic N, which is sold without the integrated headshell, can either be assembled into an existing SPU shell or, with the aid of Ortofon's optional SPU N Adapter, used as a standard-mount cartridge.

Second, Ortofon has kept the SPU in the headlines, so to speak, by introducing, from time to time, brand new variants. At first, these differed from the original only in stylus type and headshell material, the former presumably to placate those who fear their records will be harmed by anything less modern than an elliptical tip (footnote 3), the latter because, until recently, Bakelite was rather passé. But as time went on, Ortofon experimented by changing other design elements: different materials for the cantilever, coil wire, and magnet, and even different structural elements for the motor. In every case, these SPU reissues were created with the stated goal of "respecting the original sound while improving technical data."

So it is today with Ortofon's new SPU 95th Anniversary pickup head ($3400), which itself derives from the company's 2008 offering, the SPU 90th Anniversary. The earlier product is remembered for a number of innovations, including a precision-machined bit of tubing, called a field-stabilizing element (FSE), that maintains optimal magnetic flux regardless of cantilever position; and a miniature motor frame, made of laser-welded microparticles of stainless steel, designed to enhance rigidity and dissipate unwanted energies. Both features are included in the new pickup, but here the latter process, called selective laser melting (SLM), is applied to particles of titanium instead of stainless steel, resulting in a frame that is less massive but no less rigid. If anything, the motor frame of the SPU 95th Anniversary is stiffer and better behaved than that of its predecessor, thanks to an improved damping structure and an enhancement of the frame's overall geometry.

Also for the SPU 95th Anniversary model (SPU 95 for short), the magnet strength has been reduced by a slight degree, to reduce the magnet's physical influence on the motor without a significant penalty in signal output. The result, according to Leif Johannsen, Ortofon's chief officer of acoustics and technology, is a slight enhancement of the pickup's dynamics. (Johannsen adds that the rubber compound used for the SPU 95's suspension is different from that of the A90, but that its performance is the same.) Other features of the SPU 95 include a nude elliptical stylus, silver-plated copper coil wire, and a Style G headshell made from ground-up pieces of dead farm animals. (Actually, it's made from a mixture of glue and powdered wood, but I prefer my description.) The SPU 95's recommended tracking force is 3gm, and its output at 1kHz/5cm per second is 0.3mV.

Unsurprisingly, the Ortofon SPU 95 performed well in my Thomas Schick tonearm, itself a friend of the moving coil. The first things I noticed in comparing the most recent Ortofon SPU to my Ortofon Classic N—which resides, like a hermit crab, in an early Ortofon Style A Bakelite headshell—were the enduringly rich, unmistakably SPU-like bass registers of the SPU 95, and the fact that the new pickup sounded somewhat pleasantly refined. The Classic N, by comparison, sounded a little coarse: textures a bit overdone, dynamic peaks somewhat ungraceful.

The SPU 95 also impressed with its abundance of musical and sonic detail. In "The Soul of Patrick Lee," from John Cale and Terry Riley's Church of Anthrax (LP, Columbia C 30131), the SPU 95 offered greater vocal clarity than my older SPU. And with "Learning to Fly," from Tom Petty's Into the Great Wide Open (LP, MCA 10317), the reverb decay on the repeated stick-against-a-sawhorse percussion figure was far more evident with the newer SPU. But there were moments when I found myself nonetheless preferring the older pickup; the newer one sounded slightly more "scooped-out"—ie, the SPU 95's apparently less rich midrange seemed to make the frequency extremes more prominent.

But the Petty record's production, by Jeff Lynne, probably made it more vulnerable to being nudged in a decidedly hi-fi direction. On other records, such as Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch (45rpm remastering, Blue Note/Music Matters ST-84163), the A95 provided sufficient color—especially on Bobby Hutcherson's vibes, where the new pickup also did a superior job of staying clean during the most forcefully struck notes toward the end of "Hat and Beard."

The new Ortofon had good drive on "Cheyenne," from The David Grisman Rounder Album (LP, Rounder 0069), although the older Ortofon was a smidge better in that regard, doing a better job of signaling the tempo change—especially evident in the playing of fiddler Vassar Clements—from the legato A part to the more staccato B part. But the difference was slight, and both pickups were far better than the modern mean at pulling from this very slightly bright LP all the generous tone of Clements's fiddle—not to mention Grisman's mandolin, Tony Rice's guitar, Jerry Douglas's resonator guitar, and Todd Phillips's colorfully strong string bass.

Footnote 2: The 1948 Type C's cantilever shape, as well as the clear-plastic motor housing of Types A and C, can still be seen in Ortofon's CG 25 mono pickup head (a review sample of which is on its way from Denmark) and the recently retired OFD series of pickups from EMT.

Footnote 3: They won't. As I noted in the May 2011 edition of this column, most of my second-hand LPs sound good, and about 25% of those sound creepy good. I can't imagine that many of those were played with elliptical or hyperelliptical tips: Back then, it was a spherical world.

Haveahart mouse traps? (Only the varieties from that company which are made of metal. Plastic ones from that company are no good. In fact, I don't like any of the plastic, humane ones on the market.)

Poisons can leave a rotting carcass in your wall, creating smells or colonies of feeding maggots or other insects. You're right that glue traps are horrible, obviously.

Because I am only concerned about indoors, and so don't worry about getting a chipmunk or whatever, I have also used various electric shock boxes for mice and rats...to catch mice. They can work (again, the larger and more robustly constructed models.)

The trick with all these mouse traps is that one clan of mice will learn to avoid it after a number of kills. So you have to rotate various kinds of traps, as with abrasive dandruff shampoos for your scalp.

Traps also need to be cleaned of the smell of any caught mice from one clan, or else the mice who show up later may balk. The ratzapper help files suggest a solution of water and vinegar for a rinsing, I think...I would apply that approach to any reusable trap.

For the same reason, traps should be baited and placed and cleaned only with the human wearing gloves. Skin oil could similarly reduce the trap's effectiveness.

With luck this off topic post will remain until you read and delete it.