| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I owned a '66 E-type for 20 years, but my dream car was always the MkII coupe.

All in all, the SPU 95th Anniversary accomplishes precisely what Ortofon set out to do: It's a well-behaved, notably modern pickup that is quiet and imperturbable in the groove, with lots of detail and a fine sense of space on stereo records—yet it is also, identifiably, an SPU, with the sort of solid sound and fine sense of drive associated with relatively low-compliance devices. In fact, I was going to reach for a joke about how 95th anniversaries are seldom celebrated with such stiffly suspended tips, but decided against it. Instead, I'll simply say, Happy Birthday, SPU. And we all know what's coming up in 2018 . . .

More from the Deaf-Aids

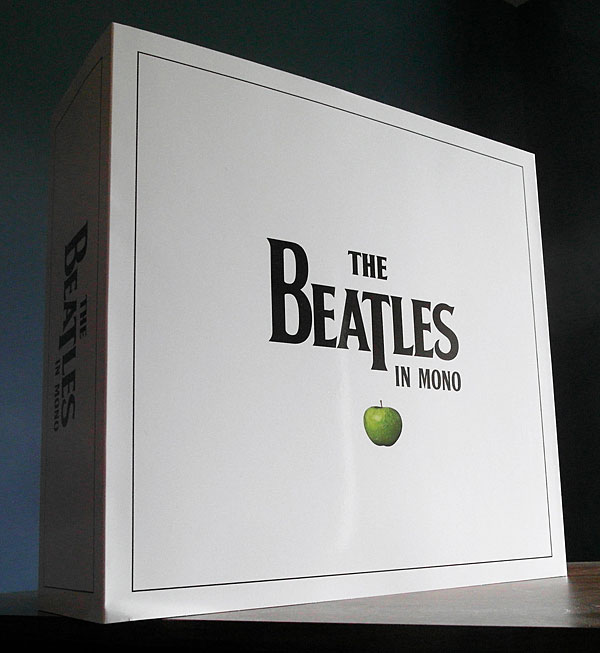

The last time I devoted a portion of this column to a Beatles release was our March 2013 issue, when I offered my thoughts on The Beatles Stereo Box Set. That limited edition combined 14 albums (comprising 16 LPs) with a 12" by 12" hardcover book, the former intended as reissues of the UK originals. Unfortunately, because those LPs were mastered from CD-quality digital files—the creation of which entailed liberal re-equalization of the original recordings—and packaged in sleeves that bore only a surface resemblance to the 1960s releases, The Beatles Stereo Box Set was not the artistic success for which we had hoped. Although initially praised by critics, in time that 2012 release picked up a few negative reviews; of the ones I've seen, none was as negative as mine, which concluded, "The real thing is gone. And, frankly, if this is somebody's idea of how to bring it back, I'd rather they not try again."

Two things happened after that—or, to be more precise, one thing happened while another went out of its way not to happen. The thing that didn't happen is that supplies of the limited-edition The Beatles Stereo Box Set never reached said limit: Nearly two years later, it remains easy to buy, often at fire-sale prices. The thing that did happen is that, by the summer of 2013, word began leaking out that Apple Records and Universal Music Enterprises intended to create and release a set of mono reissues of the Beatles' first 10 UK albums—the ones for which unique, definitive mono mixes were made with the artists' participation—and this time the LPs would be mastered from the original analog tapes; would not be subject to digitization at any point in the mastering chain; would be free from re-equalization; and would be packaged in jackets that duplicated both the artwork and the construction of the UK originals. Someone in a position of authority had obviously taken to heart the criticisms leveled at their Stereo Box Set; in light of which, my "I'd rather they not try again" soon turned to "I hope they'll try harder to get it right this time," which itself morphed into guarded optimism—and, in time, real excitement.

As I write this, my copy deadline was a few days ago, and I am without a doubt the last kid on my figurative block to receive his copy of The Beatles in Mono. (With exceptions, people who write very negative reviews tend not to get early records, let alone free records; adding insult to injury, the copy I pre-ordered in July from a prominent retailer arrived two days after the release date.) Being this late means being this skimpy: Today I can offer only a cursory review of The Beatles in Mono. But one thing is clear: Every criticism I leveled at its predecessor has been addressed.

I was worried for a moment: When I unjacketed the first LP, Please Please Me, out tumbled a bifold card, one side of which was printed with an ad for Love, the Cirque du Soleil's "reimagining" of the Beatles' hits—something I'm reasonably sure did not accompany the UK original. This insert turned out be the reissue's liner-note addendum: actually, a fine way of providing contemporary credits and comments without altering the original packaging. But I was pulled up short when I read that though the reissue engineers had tried their level best to cut the new lacquers direct from the Please Please Me masters, they'd been prevented from doing so on discovering that the fixative from the adhesive tape used to secure physical edits had gone rogue and migrated to adjacent layers on the spool: The mastering deck's playback head was getting gummed up, spoiling the sound and posing a real risk of damaging the irreplaceable master tape. The decision was made to make an analog copy to stand in for the original—something that, unlike the disc mastering itself, could be done one song at a time. This was not just a reasonable solution: It was the only solution.

My friend Jeff Friedman loaned me his mono Parlophone Please Please Me, and I set about comparing old and new using my distinctly mono-friendly analog rig: Garrard 301 turntable, EMT 997 tonearm, EMT OFD 15 mono pickup head, Hommage T2 step-up transformer, and Shindo Masseto line-plus-phono preamplifier, which Ken Shindo had modified to include a true (footnote 4) mono source selection. In a nutshell, the reissue had a virtually identical range and tonal balance to the original, and about 90% of the impact—which, as these things go, and considering the whole glue-on-the-tape-head thing, was better than I might have hoped. Adjusted for volume—the reissue of Please Please Me appears to have been cut at a slightly lower level than the original—the new one was obviously analog and entirely satisfying.

Apparently none of the other master tapes had deteriorated to such an extent, which is not to say that the task before remastering engineer Sean McGee and remastering supervisor Steve Berkowitz required less than the utmost finesse. The results they have achieved are well worth the trouble and the wait. Of the albums I've auditioned closely, only one other—1965's Help!—fell noticeably short of the original Parlophone mono, and even then by only a small margin. (The reissue has slightly grainier trebles than my original—which I found was true of most titles in the new box, but to such a lesser extent that the distinctions border on the inaudible.)

From there, all is very well indeed. The Beatles' second UK album, With the Beatles, is brilliantly served by its new reissue, with terrific touch and impact: The reissue sounds so exciting, and delivers so much of the Beatles' characteristic musical charm, one can scarcely remain seated while listening to it. And for some listeners, the reissue of Rubber Soul included in The Beatles in Mono may be the gem of the box: This brand-new mono LP is probably the best-sounding, most authentic available version of this important record.

But for my money, the new Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is the most sonically impressive of all. It is, for all intents and purposes, a literally perfect copy of the original: I'm certain I couldn't tell the new mono LP from my mono UK original. The new one has the same timbral balance, the same scale, the same color, the same range, the same punch—and the same hypnotically compelling quality, from start to finish. If I were an engineer and this was my sole accomplishment, I would be very damn proud. The packaging for the new Sgt. Pepper's is itself especially fine: Colors appear perfect (my original copy is the most uniquely well-preserved Parlophone in my collection), the stock and the coating have the right feel, the cutouts and (unused) color inner sleeve are dead on, and Apple/Universal even remembered to have the title facing the wrong way on the spine, and to omit the apostrophe.

Sgt. Pepper's gets a 10 out of 10 in packaging, while most of the other titles in The Beatles in Mono earn a solid 8 or 9: They are commendably close, although nutty collectors will notice that the card stock is a little too heavy on some, and that the serial number on the front of The Beatles is a little too big and a little too dark. (The jacket's embossed title is microscopically oversized, but that's too nutty to even mention.) That said, Apple and Universal deserve praise for their decision to print each jacket made for The Beatles with a unique serial number.

Artwork and text for all albums in the box appear to have been scanned from the originals, but the scans are exceptionally well done, without the oversaturated midtones that have detracted from earlier reissues. Obsessive collectors could point to the potential gains of rescreening photographs and resetting type, as one sees in the literally peerless work of the Electric Recording Company, but that's why the ERC has to charge £300 per LP—that and the fact that they spent hundreds of thousands of pounds in searching out, acquiring, and reconditioning their 1950s- and '60s-era, all-tube playback and mastering gear, use of which would surely have sure negated any and all remaining reservations regarding the new vinyl's sound. (The sonic score for The Beatles in Mono, averaged over 14 LPs, is close to 9 on a scale of 10; none of the new ones are actually better than the old, and I wouldn't expect them to be.) But that's the cost of true perfectionism: In programme as in equipment, the last 10% of gains are the most expensive of all to achieve.

My only lingering complaint: Except for The Beatles and Sgt. Pepper's, none of the LPs come with the correct inner sleeves—which, for most of the other titles, would have been the one that advises the buyer to "Use an Emitex cloth to clean your valuable records." No big deal, but it seems that it would have been such an easy thing to do.

The Beatles in Mono is doubly recommendable. As someone who has beaten the drum for mono LPs since long before my first column for Stereophile (this one being No.144), I'm comfortable in suggesting that, with the appropriate playback gear, you will hear more color, impact, verve, swing, and sheer humanity of music-making from these LPs than from any other format or vinyl edition other than the Parlophone originals. And because the mono mixes represent the Beatles' true intentions, listeners whose previous experience is limited to the group's catalog in stereo will be shocked by the musical distinctions found throughout these reissues—especially on The Beatles.

If the boxed set is sold out by the time you read this, you'll find just as much pleasure in having individual titles from this series. The book is lovely, and contains a few mildly revelatory details, but for now I've set aside the actual box in favor of keeping the new LPs on the shelf, next to the old. They're easier to get at that way, and these days I'm getting at them a lot.

God bless the company that heeds criticism, especially when the air isn't exactly thick with the stuff.

Haveahart mouse traps? (Only the varieties from that company which are made of metal. Plastic ones from that company are no good. In fact, I don't like any of the plastic, humane ones on the market.)

Poisons can leave a rotting carcass in your wall, creating smells or colonies of feeding maggots or other insects. You're right that glue traps are horrible, obviously.

Because I am only concerned about indoors, and so don't worry about getting a chipmunk or whatever, I have also used various electric shock boxes for mice and rats...to catch mice. They can work (again, the larger and more robustly constructed models.)

The trick with all these mouse traps is that one clan of mice will learn to avoid it after a number of kills. So you have to rotate various kinds of traps, as with abrasive dandruff shampoos for your scalp.

Traps also need to be cleaned of the smell of any caught mice from one clan, or else the mice who show up later may balk. The ratzapper help files suggest a solution of water and vinegar for a rinsing, I think...I would apply that approach to any reusable trap.

For the same reason, traps should be baited and placed and cleaned only with the human wearing gloves. Skin oil could similarly reduce the trap's effectiveness.

With luck this off topic post will remain until you read and delete it.