| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I vote for the Marantz CD63 Mk II KI Signature.

These successes, Kawakami says, "debunk the shibboleth of the industry, that you can't compete with free. Now we have a template."

I agree—or, at least, I want to agree. I want to live in a world where enough people care about the quality of music reproduction that I can still make a living by congratulating them for it.

Champing at the bit

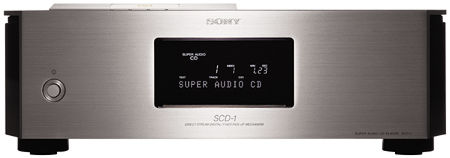

I'm still glad I bought my mildly expensive and outrageously heavy Sony SCD-777ES SACD player when I did. In fact, my only real regret is that I didn't buy their even more expensive but no heavier top-of-the-line machine, the SCD-1, whose balanced outputs would have been so useful during that damn Ayre AX-7 review (Stereophile, October 2003—but let's not go there). The thing is, those first two Sony SACD players show every sign of becoming classics, evidence for which includes the following:

1) After five years, the SCD-1 is still in Sony's product line, and apparently still selling—remarkable for any product from what is essentially a mass-market brand.

2) The people who bought the SCD-1 and SCD-777ES players seem to be keeping them. If anything, they're having them modified by the cottage industry that's sprung up around them. (In a future column, I hope to report on the work that John Tucker of Exemplar Audio is doing along these lines.)

3) Both are well-made and well-styled, with a simple, austere look that's rare among digital source components.

4) Both sound good and play music convincingly well.

5) Both are based on DSD technology—which is actually a far sight simpler than its predecessor, PCM.

Simpler? Yes: In the years since the compact disc first crawled from the slime, the chips used for digital-to-analog conversion and digital filtering have improved dramatically. But those increases in processing power have been used, for the most part, to address flaws in the system: noise was shifted up and away from the audible spectrum, algorithms were applied to enhance resolution over portions of the bandwidth, and so forth.

But the goal for SACD was not another Band-Aid, howsoever clever. This really is a whole new system: one-bit digital audio done right, without the need for decimation and interpolation stages (hence the "Direct" in Direct Stream Digital). As David Kawakami observes, whereas PCM doesn't resemble anything in the natural world, DSD is a closer facsimile of analog sound: You can even listen to a DSD signal itself and hear that it resembles music; a PCM signal sounds like you've called your fax machine by mistake.

Newer SACD hardware is simpler still: Those first two Sony players required two separate laser heads—one for regular CDs and another for SACDs, with their very much smaller pits. All their new machines use a single laser pickup with a self-adjusting focal length. Which is pretty cool.

Forgive me for thinking so, but that's something else that characterizes most true classics, in any field: Elegance. Simplicity. Long after we've forgotten the six-way speakers that use three different kinds of transducers, the hybrid preamplifiers with insanely complex signal paths, and the motorized tonearms meant to "correct" all those off-center records, we will continue to cherish the Spendor BC1, the Conrad-Johnson PV2, and the Rega Planar 3. And, I think, the Sony SCD-1.

Even though the first CD players will never be regarded as classics—and what an indictment that is, when so many old turntables still sound so fine—I think there's a good chance those first two SACD players, Sony's SCD-1 and SCD-777ES, will be seen in a very positive light for many years to come.

The day the music fell and broke its hip

But will I forever cherish those first 20 or so SACD titles I bought? Er, no. More than once during the first two years I owned my Sony SACD player, when I was desperately trying to find SACDs I actually wanted to own, I was reminded of how I felt back in 1974, when I was 20 years old and standing in a record store, looking with the same kind of desperation for something new that was also halfway decent. With exceptions—I remember enjoying Roxy Music's Country Life, although that's now one of my least favorite Roxy albums, and the wittily named Electric Light Orchestra halted their slide toward mediocrity just long enough to produce the genuinely moving Eldorado—I came away empty-handed. 1974 was the kind of year that could drive a kid to jazz—or worse.

Think back: In 1974 the Byrds were no more, having left on the sour note of that awful reunion album for David Geffen's new Asylum label; Paul McCartney took the year off; and John Lennon released the forgettable Walls and Bridges, completing the hat trick he began with Some Time in New York City (1972) and Mind Games (1973). Need more convincing? In 1974 Dylan and the Band released Planet Waves, perhaps the most over-pressed LP in history (also on Asylum—see the pattern?), Randy Newman lost his footing with the monotonous and overrated Good Old Boys (not on Asylum, but with its roster of L.A. session bores, it might as well have been), and Jethro Tull released War Child, their weakest and one of my top picks for worst pop album, ever. In 1974 Bowie and the Stones had lost it, Elvis was a sweaty joke, nobody outside of Memphis had heard of Big Star yet, and Leo Sayer began his recording career. God have mercy.

So it goes in a different sense today. I bought Leonard Bernstein's Columbia Mahler First on SACD, even though I already had better performances in my LP and (regular) CD collections (most notably by Jascha Horenstein and Dmitri Mitropoulos). I also bought Bruno Walter's pallid, unconvincing Beethoven Sixth and Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells, the less said about which, the better. (Wait a minute: What year did Tubular Bells first come out...?) Each was listened to a couple of times, then filed.

Then something good happened: Philips began releasing all of conductor Valery Gergiev's new recordings on hybrid discs. I've been a fan ever since I bought Gergiev's superb Tchaikovsky Fifth in 2000 (with the Vienna Philharmonic, on a regular Philips CD), and I watch for his discs with greater than average hope. I would've bought his new performance of the Shostakovich Seventh, a live recording with the combined Kirov and Rotterdam Philharmonic orchestras (Philips 470 623-2), in any event—and the thrilling, colorful performance rewarded my best expectations. But having it on a fine-sounding SACD is all the sweeter. Very highly recommended.

And that's the key: a brand-new recording that I would have wanted anyway, regardless of format, that just happens to be on SACD. If this sort of thing can happen once, it can happen any number of times. In the most important sense of all, then, SACD has finally begun to arrive.

Yes, I've bought some of the Stones and Dylan discs, and they're nice, too (although Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited sounds spittier than I think it should), but reissues aren't the point: Reissues may be the foundation for now, but they can't be counted on to drive this thing forever, or else it's bound to crash. When the day comes that I can go to my favorite record store and know that any and all new material from, say, Built to Spill, the Foo Fighters, Michael Penn, Tom Petty, and Doc Watson is available on a hybrid disc, then I'll know that SACD's arrival is complete.

And that, according to David Kawakami, is Sony's goal. "It's a business," he says, "and we've invested a lot in SACD. We have 10 players in our line right now, with semiconductors produced just for those machines. So, yeah—we're committed." But the format's initial success, he says, "bodes well for everybody: The good news is that people haven't stopped wanting to get closer to their favorite artists."

I vote for the Marantz CD63 Mk II KI Signature.