| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I love the Herrmann scores and the opening to The Shining is one of my favorite Kubrick moments for sure.

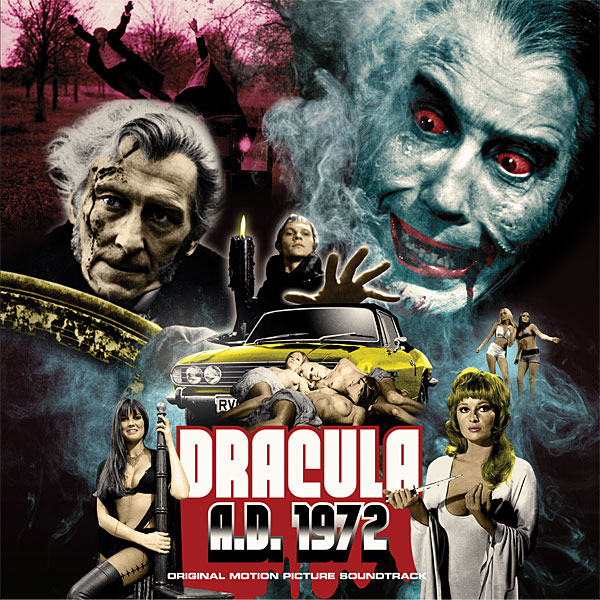

Then there were James Bernard's tense scores for the Hammer films—like Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), starring Christopher Lee—that my parents somehow let me see in a theater when I was seven, as part of an afternoon of bargain monster movies that included all the sourballs and unbuttered popcorn you could wolf down. Scared to death, my life was forever changed.

Finally, as someone who's complained mercilessly that author Stephen King had not and perhaps never would be done right by on screens large or small—a feeling confirmed when I heard that Kubrick omitted the topiary scene from his version of The Shining (1980)—I was stunned into silence by the ominously effective tolling of horn-like synthesizers in Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind's main title theme for that same film. The theme is based on Dream of a Witches Sabbath, from Hector Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique, and "Dies Irae," the 13th-century hymn included in the Requiem Mass. The creeping percussion and high synth trails sounding like ghosts screaming, as slow, rolling helicopter shots show the Torrance family driving up into the mountains (actually, Glacier National Park's Going-to-the-Sun Highway), very effectively set the scene for what is perhaps the ultimate haunted-house story.

Music and films have always been inextricably linked. From those first silent-movie scores banged out on out-of-tune upright pianos, to the full-blown orchestral arrangements of Hollywood's Golden Years, to more recent computer-generated scores and beat-heavy cues, music has played nearly as large a role as image in the success of film as an art form.

After perhaps musicals and cartoons (All hail, Raymond Scott!), no film genre has used music to greater effect than has horror. Examples of how important music is to horror films abound. With apologies to Mike Oldfield, who has always had misgivings about how his music was used in The Exorcist (1973): Even with the pea soup and Linda Blair's head spinning around, that film wouldn't be half as scary without Tubular Bells. And could there even be a shower scene in Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) without the unforgettable screeching of Bernard Herrmann's high strings? Best of all, many horror soundtracks are actually very listenable and enjoyable without their accompanying images. I don't know of a better party record than Jerry Goldsmith's brilliant score for the original Planet of the Apes (1968).

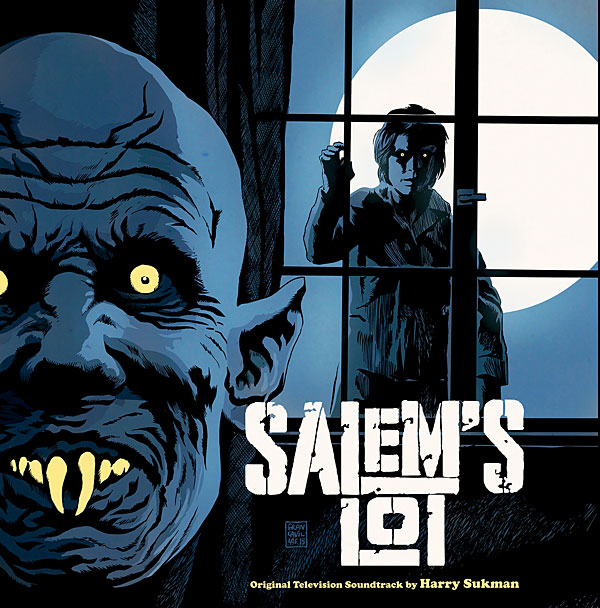

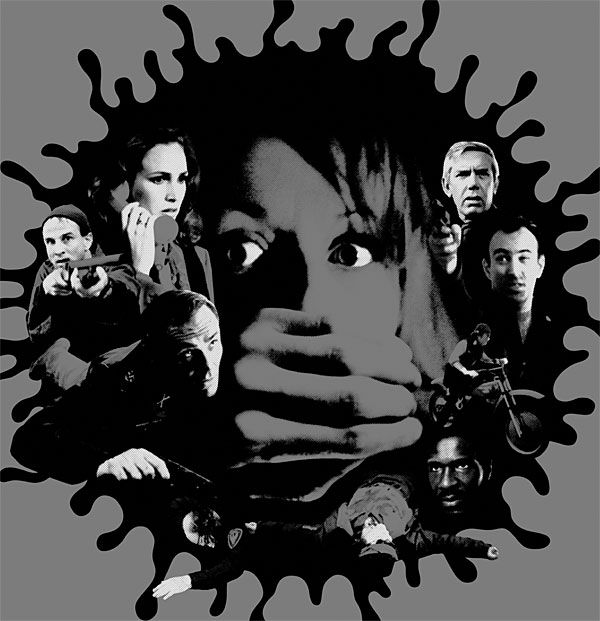

Coupled with the resurgence of the vinyl LP, several small independent labels that focus on releasing or re-releasing horror-film soundtracks in super-premium packaging and multicolored vinyl have sprung up since 2012. Their products feature some of the most elaborate LP packaging yet devised in the unlikely and continuing resurrection of the LP.

As I wrote in last month's "Aural Robert," Rob Maushund of Stoughton Printing, in Los Angeles, turned me on to a small Chicago-based record label, Waxwork Records, for which Stoughton had done some incredibly complex LP packages. Asked to name his most challenging packaging job ever, Maushund without hesitation pointed me toward Waxwork's recent release of Ennio Morricone's pulsing, heartbeat-like score for John Carpenter's The Thing (1982), which—forgive me, James Arness fans—thanks to Kurt Russell puts the original, The Thing from Another World (1951), to shame. Housed in a die-cut slipcase made to look like the cracked ice of the film's Arctic setting, the LP itself was given the look of a polar icecap with rings of black, white, and blue vinyl. Intrigued, I spoke with Kevin Bergeron; he and his wife, Suzy Soto, founded and own Waxwork.

"When we started, in 2013," Bergeron said, "there were a lot of things we weren't seeing in the soundtrack market. We wanted to put Waxwork's spin on releasing horror soundtracks by tracking down, for example, the original master tapes, which other companies weren't doing at the time."

The specialized yet thriving market for horror scores—subscriptions to Waxwork's annual slate of releases routinely sell out—was first tapped almost simultaneously, in 2012, by two labels, Mondo and Death Waltz, who merged in 2015. Although Waxwork won't release their pressing numbers, Spencer Hickman, founder of Death Waltz, says that Mondo and Death Waltz now press between 500 and 5000 copies of each vinyl release. All three of these new labels also reissue non-horror titles; Waxwork has released the soundtracks to both Taxi Driver (1976, Herrmann's final score) and The Warriors (1979), and three of Mondo's highest-profile titles are the soundtracks to the Back to the Future trilogy.

Hickman, whose title in the merged company is the very wonderful Head of Music, was recovering from a viral stomach disorder when he graciously took my call (and subsequent e-mails). He understands the market for beautifully done LP reissues of horror-film soundtracks because he's, well, one of them. "I have horror tattoos," he said. "I collect all sorts of useless things. I'm in my house right now looking at a cube from Hellraiser [1987] and a sphere from Phantasm [1979] that I want but don't really need. Horror fans are rabid. They're collectors. And there's a really nice sense of community with horror fans as well." Hickman's list of favorite film composers includes Fabio Frizzi, John Carpenter, Bruno Nicolai, and Steve Moore.

Film soundtracks are generally thought of as tepid sellers that, every once in a while, catch lightning in a jar, usually thanks to a hit single or two—à la Saturday Night Fever. Given that reality, it's not surprising that one of the biggest reasons there's now a profitable niche market in horror-film scores is because so many were never released in the first place.

"Early in the resurgence of the LP, even events like Record Store Day seemed to have bypassed soundtracks, and that kind of puzzled me," Hickman said. "I'm a big vinyl head; I worked in record shops all my life and at the time I ran London's Rough Trade East record store. I couldn't understand that these things I really liked weren't available to buy anywhere. I've got, like, a fairly decent-sized collection of soundtracks, and I just thought it's madness that there isn't a new version of Assault on Precinct 13 [1976] available to buy, or that a copy of the soundtrack to The Thing costs $300 or whatever, because it's so rare."

"More than half of our discography has never been issued," Bergeron said. "My Bloody Valentine [1981], Shock Waves [1977], C.H.U.D. [1984], Black Christmas [1974]—none have ever been released on any format."

In talking about film music, it's crucial to recognize the difference between the score—a through-composed body of music to accompany the entire film—and the soundtrack, which can contain much or all of the score but also everything else heard: dialogue, sound effects, pre-recorded popular-music hits, etc.

Like other recordings, mono film scores recorded before the widespread adoption of stereo remain in mono on these new releases. Also like many non-soundtrack recordings, film scores were often judged to have limited sales potential, and so their master tapes were stored improperly or worse. Most of the recordings all three labels are working with are sourced from 2" reels on which the original score was recorded before being transferred to the film's soundtrack. Audiophiles will be most interested in these releases because, from the 1960s through the 1980s, film scores were generally well-recorded on analog tape. Most also greatly depend on a wide dynamic range from loud to soft, from light to shade, to achieve their dramatic effects.While both Bergeron and Hickman mentioned using remastering engineers, I got the feeling neither label engaged in much heavy sonic restoration. If the source was too compromised, they'd pass on the project.

"The Legend of Hell House [1973] is one of my all-time favorites," Hickman told me, "and the score [by Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson] is phenomenal, but the tape of the score is lost. What's on the Blu-ray is taken from a source that's not hi-rez and cannot be separated from the film. There's also been one film where there aren't tapes, and so we tracked down a sealed copy of the original record and recut it from that, with the composer involved.

"There's also a project that's ongoing at the moment—it's the score to Let's Scare Jessica to Death [1971]," Hickman continued. "The score is folk and electronic music, really good, and the composer, Orville Stoeber, and I have been going back and forth now for like three years back. He can't find the tapes. He's considering re-recording one of the tracks.

"We're also doing a new release of Hellraiser. It's a benchmark movie, one of the last '80s classics whose soundtrack hasn't been released. We just baked the original tapes, had them transferred, and approved by composer Chris Young. That stuff isn't cheap, but listening to what was on the tapes is incredible. We may not shout about it enough, but we always go to the original master tapes whenever possible."

Waxwork's Kevin Bergeron has his own war stories of searching for original recordings. "Sourcewise, every release is a little bit different than the last. It's really a mixed bag. For the most part, we acquire the original masters, and if there is any sort of reworking that needs to be done, we work with our mastering engineer.

"Many of these soundtracks were never intended to be commercially released, so a lot of times we get masters and they are in horrid condition. Or it's a tape of, like, 80 different cues that we have to thread together to make a cohesive listening experience that's pleasurable to the ear.

"On Rosemary's Baby [1968], we actually went on a crazy mission to find out where the score [by Krzysztof Komeda] was. For whatever reason, it was in Melbourne, Australia. Somebody there had the master tapes, and we acquired those. It was the very last time those tapes will ever be transferred, because they are not in great shape."

Besides lovers of horror films, LPs pressed on colored vinyl, and lush, lavish packaging, part of the audience for these records are comic-book fanatics, a crowd that values the seen as much as the heard. Mondo, Death Waltz, and Waxwork all share a devotion to creating one-of-a-kind "deluxe" packages that can include liner notes from a film's director and/or composer, newly commissioned cover and inside jacket art, and new art prints, all of it slotted into heavy jackets of coated cardboard stock. These companies have also taken the art of mixing vinyl colors to a new high. Up to three or four colors in a single LP are now common practice. In addition, Waxwork is launching a line of all-original comic books with companion soundtracks on vinyl, for what Bergeron calls a "fully immersive experience." Waxwork has created another, even more immersive experience, one that, appropriately enough, involves that driving force of vampires and axe murderers alike: bloooooddddd!

Begeron: "It was a crazy, crazy endeavor. We were going to release [Harry Manfredini's] soundtrack to Friday the 13th [1980], and I figured it would be a really cool collectible variant if we released a vinyl record with what looked like blood inside it. There wasn't a pressing plant anywhere that was willing to do it. Even people that I knew had done it before didn't want to do it."

Eventually, 100 vinyl copies, each with something approximating human claret inside, were pressed by Erika Records, in Buena Park, California.

"What we used to make it look like blood . . . well, I don't even know what it is, because the person who made them was very smart and very secretive with us."

How frightfully appropriate!

I love the Herrmann scores and the opening to The Shining is one of my favorite Kubrick moments for sure.

Bravo Robert! You are on a great summer roll. I bought the Lad From Tupelo and I am so engrossed I haven't made it to the third CD yet. Now I must start shopping for blood vinyl and Raymond Scott issues. Have you written about Scott? Is there a good place to start?

your biggest fan,

herb

Great reading, especially the treasure hunts for the lost and forgotten. Probably my all-time favorite score is in Fright Night, the instrumental by Brad Fiedel - Come To Me. It weaves itself into the film in numerous places, but the longer instrumental in the room where the vampire seduces the girlfriend and bites her is the ultimate. Unfortunately I don't think that's been released.

Edit: Various versions have been released or are on youtube, but those are bland and repetitive compared to the main theme actually in the movie as I described.