| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

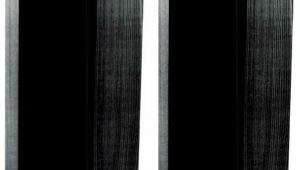

Joseph Audio RM33si Signature loudspeaker Page 3

Layer on Layer

I enjoyed listening to the RM33si as much as, if not more than, any component I've auditioned in the last five years. The speakers sounded good from any point in the room, and permitted an emotional connection to the music that was magical. The integration of the three drivers was seamless and transparent, and the midrange driver delineated detail like an expensive spa treatment for your music. While in my original estimation the RM22si evoked the clarity and piquant detail of a good white wine, the RM33si suggested a more complex flavor—like a fine old Bordeaux revealing layer on layer of body and bouquet in an interplay of earth tones, grapes, and barrel wood as the wine opens up in the glass, mingling with the air to reveal a web of heretofore unimagined sensations.

I enjoyed listening to the RM33si as much as, if not more than, any component I've auditioned in the last five years. The speakers sounded good from any point in the room, and permitted an emotional connection to the music that was magical. The integration of the three drivers was seamless and transparent, and the midrange driver delineated detail like an expensive spa treatment for your music. While in my original estimation the RM22si evoked the clarity and piquant detail of a good white wine, the RM33si suggested a more complex flavor—like a fine old Bordeaux revealing layer on layer of body and bouquet in an interplay of earth tones, grapes, and barrel wood as the wine opens up in the glass, mingling with the air to reveal a web of heretofore unimagined sensations.

The RM33si sounded like a much bigger speaker. The review pair not only depicted wonderful senses of depth and breadth, but of height as well. The integration between the drive-units was absolutely seamless. The proof of the pudding was in the remarkable transparency and detail of the overall presentation, built on rock-solid bass resolution. The way big transients were reproduced with visceral impact was always impressive, yet I was never aware of the bass driver calling attention to itself; nor did it add woof or bloat to lower-midrange frequencies, or portray the deep bass in a one-note manner while imposing itself on adjacent frequencies and smearing images. To my ears, not only did the RM33si seem to go down flat and clean to 28Hz, but when I played the 1/3-octave warble tones at -20dB from Stereophile's first Test CD (STPH002-2), I discovered that the speaker offered full bass output at 31Hz, and still useful low-frequency energy at 20Hz. I'm talking audible, physically palpable bass.

This helped explain how the RM33si could impart such an authentic sense of the ambience and holographic qualities of a large concert hall. On the Andante and Allegro molto of Bart&3243;k's delightful, wildly percussive Piano Concerto 1 (Yefim Bronfman, Esa-Pekka Salonen/LAPO, Sony Classical SK 66718), I was most impressed by how the RM33si sorted out complex colors, textures, and dynamics—particularly the true attack, decay, and upper harmonics of a solitary snare drum and cymbal. It accurately depicted the recording's distant perspective while retaining appropriate reserves of weight for the subtle gong and timpani transients and the enormous bass-drum transients, never obscuring the delicate bass textures of the orchestra but retaining pianistic details like a sensitive conductor.

Even on the torturous cannon shots of Telarc's new DSD recording of Tchaikovsky's Overture 1812 (Erich Kunzel/Cincinnati Pops, SACD-60541), the RM33si's managed to accurately translate the left-to-right progression of the cannonade from well behind the orchestra while maintaining a firm, undistorted orchestral image. The subsonic impact in the small of my back was frighteningly vivid. On the second pass, however, the Musical Fidelity Nu-Vista 300 power amplifier shut itself down. Quite a feat, considering that the Nu-Vista 300 pumps out 300W into 8 ohms.

The layered midrange resolution and sweet, natural high-frequency extension of the RM33si made it perfect for all manner of acoustic music and vocals. I recently bought the Talich Quartet's complete set of Mozart's string quintets (Calliope CAL 3231-3); the quintet in g, K.516, offered stunning proof of the RM33si's integration, coherence, and frequency integrity from the midbass up through the lower treble. I was immediately aware of the Talich and violist Karel Rehák sitting in a semicircle, and when the cello entered, perfectly centered toward the back, the effect was so full-bodied yet transparent that I had no sense of the sound coming from any speaker source. More telling than the spatial cues was the wealth of detail with which each player's bowing and dynamics were rendered, both individually and as part of a greater acoustic blend—which the RM33si revealed to be a tad on the bright side.

Then, on Richard and Linda Thomson's "The Great Valario" (from Watching the Dark: The History of Richard Thompson, Hannibal HNCD 5303), Linda's haunting soprano floated freely front and center in a deep, perfectly delineated ambient space; I could practically feel the notes forming in her diaphragm and working their way up her throat as she forms and articulates each phrase with tongue, teeth, and lips, measuring the intensity of her attack against the sound coming back at her from the clearly limned acoustic boundaries—all without megaphoning or veiling the elemental twang of Richard's acoustic guitar or Pat Donaldson's tolling acoustic bass.

- Log in or register to post comments