| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

John Adams Page 2

Matson: Going forward, for the recorded catalog of classical music old and new, in terms of compensation, in regards to streaming and so forth: Can this work, or are we done?

Footnote 11: Available in a recording by Leila Josefowicz, David Robertson, and the St. Louis Symphony CD, Nonesuch 557170-2.

Adams: I talk a lot about this with my friend [Nonesuch Records President Emeritus] Bob Hurwitz. If it's an opera, you want the wonderful essays, and the libretto. There's also the aspect of just having an object, if you really care about an album. You go to Amazon now, and they sometimes don't even list the composer, because the whole thing's been done by an algorithm.

Matson: You once described opera as "the spoiled brat of the arts." Isn't that one of the things that makes it great—its total impracticality?

Adams: It's terrifically expensive, it never makes money back, but it's an art form to the max, the way people sing, the emotional level. I'm drawn to it because the theatrical/music form allows me to explore subjects on a mythical level.

Matson: Perhaps symphonic music has to struggle more now?

Adams: It's a challenge. What I have to deal with is marketing people throughout the country. If a piece of mine is on the program, they try to hide the fact! [laughs]. I went to a wonderful orchestra just a few months ago, and I did this big piece, Scheherazade.2 (footnote 11) with a fantastic soloist. The marketing that week on the radio and the newspapers was: "This week! Appalachian Spring!" [laughs]. What drives me crazy about the classical music world is that it seems that the conventional impression of it is that it is an art form of the past. For example, you get The New Yorker, and you look at what the Met Opera's doing—with one exception each season, it's the same repertoire. Most symphony orchestras—they are a little more progressive, but they grasp tight their Beethoven cycles and their Tchaikovsky, and they're all hostage to megastars.

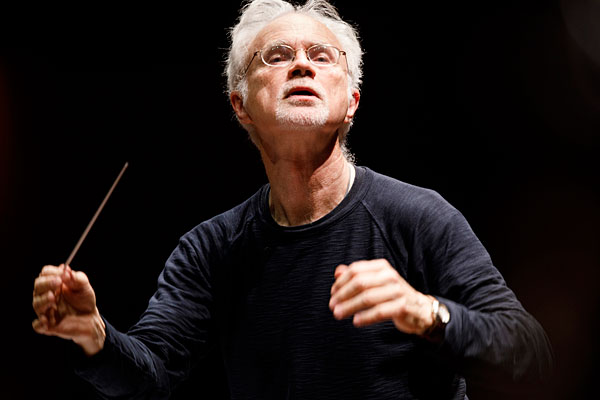

Matson: You conduct your own music, except when you don't. Comment on the composer/conductor relationship.

Adams: I'm very lucky that I can do that. I happened to grow up as a performer, and I was interested in conducting, and I got a lot of experience of it. Now I'm very spoiled, as I am able to conduct the world's greatest orchestras. I've said it many times, but it's a meaningful expression: conducting is the yin, and composing is the yang for me. They are very different activities. Composing is very solitary and hermetic, but I am very practical when I am composing because I know what's doable.

Matson: Are we done with 'isms'?

Adams: Yeah, I think we are in a post-style period. I do a lot of music by young composers, and what strikes me is that there is no accepted prestigious style, like there was back when I was in college. In those days, you were either uptown or downtown. A lot of critics were very intimidated by people like Boulez and Carter and believed that there was only one way to do something. Now, each composer has found his or her own method of expression, and it ranges all over the bandwidth. I'm seeing a young generation that are in their 20s or early 30s, and they seem to be discovering the '60s all over again. They're doing pieces that sound like Stockhausen! [laughs].

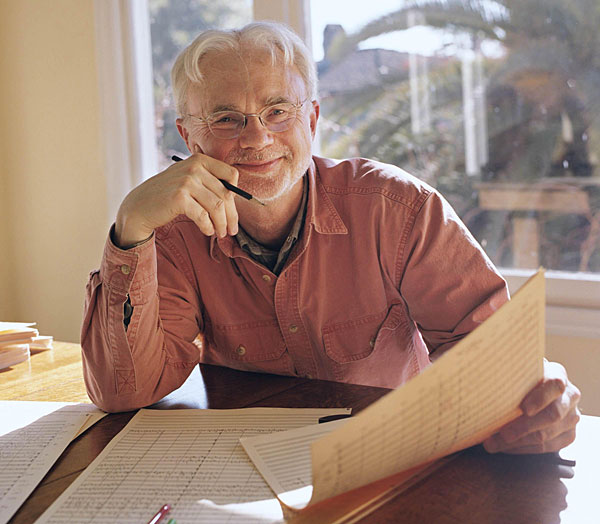

Matson: How does the craft work for you now? Do you write at the piano, use a home studio for your process?

Adams: I'm not a pianist, and before computers, composing was really difficult for me, as it was hard to conceive a complex work.

Matson: I recall you had a pretty sophisticated midi synth setup for creating mockups of pieces so you could hear them.

Adams: I still do. But what makes me different from most younger composers is that my final stage is paper and pencil.

Matson: How do you think the technology is influencing music-making now?

Adams: In many ways. A negative impact has been composing software. The default is often 4/4 meter, and the quarter note equals a 120 tempo. I see how the kids accept that as a starting point—they are working within the grid that the software wants it to be. The software is having a profound influence.

Matson: Here come some Dead Composers—we'll set the living ones aside: Beethoven.

Adams: Perfect balance between high energy and a deep anima.

Matson: Puccini.

Adams: Good ticket sales. Good vocal writing.

Matson: Bartok.

Adams: Underappreciated. Profoundly original. Unique harmonic sense.

Matson: Wagner.

Adams: Oppressive. Long-winded. Genius.

Matson: Stravinsky.

Adams: He wears a coat of many colors. For composers, it's impossible to escape his influence.

Matson: Bach.

Adams: He's the canon. He's the perfect composer in a way.

Matson: Ravel.

Adams: Oh, I love Ravel. He's a perfect blend of sentimentality and erotic passion.

Matson: Sibelius.

Adams: A handful of great works. His early works are the most out-front and passionate. My goal in life is to conduct all seven of the symphonies. After this year, I will have three to go.

Matson: Copland.

Adams: What I like about Copland, in the early works, is the mixture of Stravinskyan rhythm and jazz harmony. I like his populist music more than his "serious" music.

Matson: Jazz composers?

Adams: I was in a hotel room in Dallas for a week recently, and I got obsessed with Bill Evans on YouTube.

Matson: Has anyone called you the "Dean of American Composers" yet?

Adams: Oh yeah. At least they haven't called me "The Grand Old Man"! [laughs].

Footnote 11: Available in a recording by Leila Josefowicz, David Robertson, and the St. Louis Symphony CD, Nonesuch 557170-2.

- Log in or register to post comments