| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Infinity IRS Beta loudspeaker Measurements

Sidebar 3: Measurements (from June 1989, Vol.12 No.6)

Footnote 1: Audio Control Industrial SA-3050A 1/3-octave spectrum analyzer with calibrated microphone and integral pink-noise source; Heath/Zenith PC-controlled 8-bit storage 'scope; Fluke 87 true-RMS multimeter; homebrewed computer-controlled sinewave, squarewave, and pulse generators.—John Atkinson

As I had dragged my motley collection of test equipment (footnote 1) over to Larry's listening room to carry out a set of measurements on the Mirage M1 loudspeaker he reviewed elsewhere in this issue, I thought it might be a good idea to quickly take a look at the measured performances of another of the high-end models that happened to be in Santa Fe, Infinity's $12,000/pair IRS Beta, which J. Gordon Holt had discussed in the September 1988 and January 1989 issues of Stereophile (Vol.11 No.9 and Vol.12 No.1, respectively).

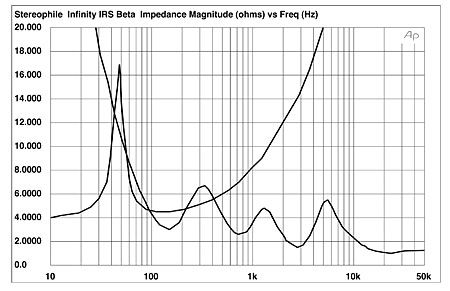

You may remember that JGH had an unfortunate series of consistency problems with his review samples of the Infinity IRS Beta. The final samples to arrive in Santa Fe, however, were both well matched and sounded as good as the high price promised. Before sitting down to some listening and response measurements, I looked at the speaker's impedance. Fig.1 shows the impedance modulus for both the woofer tower (without its servo drive connected) and the midrange/treble panel. With a fundamental 4 ohm characteristic, the woofer can be seen to be tuned to 49Hz, with its impedance rising above 400Hz due to the increasing voice-coil inductance. In use, one would expect the servo-drive system—one drive-unit of each tower's four is fitted with a high-precision accelerometer to send an error signal back to the LF crossover/equalizer—to extend the response significantly below the tower's bass-tuning frequency.

Fig.1 Infinity IRS Beta, impedance magnitude of woofer tower (top above 500Hz) and midrange/treble panel (2 ohms/vertical div.).

The impedance of the mid/treble panel drops significantly below 4 ohms for much of the time, reaching minima of 3 ohms at 150Hz, 2.6 ohms at 720Hz, 1.5 ohms at 2750Hz, and approximately 1 ohm at 23kHz. It will therefore present any driving amplifier with an extremely demanding task in terms of being able to deliver current, particularly in the lower midrange where the bulk of musical energy lies. On the positive side, the extremely low moving masses involved in Infinity's EMI drive-units and the well-damped nature of the fundamental resonance of each unit will not give the driving amplifier any problems with back EMFs, as is the case with some conventional dynamic drivers.

An important point that should be noted is that the overall low nature of the impedance means that the speaker's frequency balance will be much more amplifier-sensitive than normal. Certainly, a traditional tube amplifier with a rising output impedance with frequency will produce a sound that is much mellower in the treble than will a modern high-performance solid-state design. This was certainly the case in my experience, where Mark Levinson No.20.5 amplifiers produced a sound from the Betas possessing considerably more HF energy than the VTL 300 tube amplifiers.

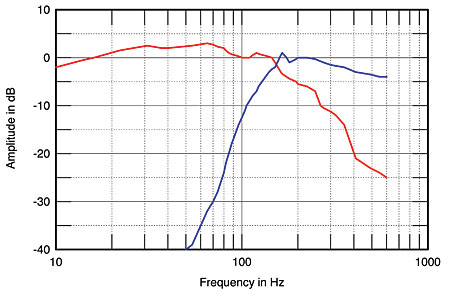

At the opposite end of the frequency spectrum, fig.2 shows the nature of the crossover between the Beta's two systems. The response of the woofer tower with the servo drive connected and that of one of the Large-EMIM drivers on the main panel were measured in the nearfield, ie, with the microphone placed as near as possible to the center of the relevant diaphragm. The woofer low-pass filter was set to its maximum of 164Hz. The LF response can be seen to be extremely extended, being –3dB at an astonishingly low 16Hz (!), and is ostensibly flat through the three octaves above that frequency. This is true subwoofer performance. The woofer roll-off reaches 12dB/octave above crossover, but the midrange panel can be seen to roll out very steeply below 160Hz, with a 24dB/octave characteristic.

Fig.2 Infinity IRS Beta, nearfield woofer and midrange responses.

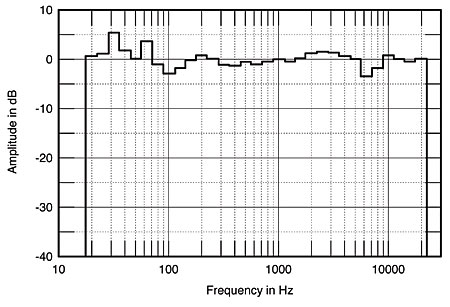

It might be thought that the result would be a seamless blend between the two drivers, but as shown in fig.3, which is the spatially averaged, 1/3-octave response of the Beta taken at the listening position with all its HF tone controls set to their mid positions, I couldn't eliminate a slight lack of energy in the region around crossover. I suspect that this is due to it being hard to match the essentially omnidirectional radiation pattern of the woofer tower with the dipole, steep-roll-out midrange pattern. The graph shows the best that I could achieve in Larry's room by adjusting the woofer positions, bass contour and level controls, and the woofer polarity.

Fig.3 Infinity IRS Beta, spatially averaged, 1/3-octave response in LA's listening room.

Note that while the bass does feature true 20Hz extension, the two dominant LF modes in Larry's room, around 30Hz and 60Hz, are sufficiently excited that their effect is not eliminated by the spatial averaging used to derive the response curve. This gave problems in setting the optimum bass level in that when the upper bass was sufficiently full, the low bass was excessive. When the low-to-mid–bass balance was best, it then sounded a little separated from the main body of the music.

The exact match between the Beta's bass and midrange will also be a matter of personal preference. For example, though that shown in fig.3 was to my tastes, Larry found it a little bass-light. Above the bass/mid crossover region, the IRS Beta is flat from 160Hz to 2.5kHz, the averaged in-room response meeting superb ±1dB limits. The rise in the presence region is very dependent on the listening axis. With the Betas firing straight ahead, the flatness of response at a 39" listening height—a reasonably high chair, I admit—extended to above 4kHz, but at a higher listening height than that, the 3kHz region became a little too exaggerated. The broad depression between 4 and 8kHz lies in the exact region handled by the EMIT tweeter, and was present on all measuring axes. Resetting this driver's control to its maximum reduced the depth of the dip to around 2.5–3dB on-axis, but did not remove it entirely. I suspect that it is a crossover artifact.

In the high treble, the in-room response is flat, which, given the increase in sound absorption in-room at these frequencies, represents a significant amount of additional energy considering the fact that the microphone was 3m distant. The speaker has very wide dispersion in this frequency region, even in the vertical plane; as might be expected, the degree of extreme-HF boost increased with the microphone on-axis with the tweeter/supertweeter, but this is an unrealistically high listening position. In a relatively live room, however, it will lend the room's reverberant field a somewhat whispy, oversibilant nature. This measurement was taken with each panel driven by a Levinson No.20.5; as mentioned earlier, something like a VTL 300 monoblock would bring this region down in level to provide a better match to the low treble. Surprisingly, reducing the S-EMIT drive to its minimum with its level control made no significant difference in the measured exaggeration.

Though overall he was extremely impressed by the IRS Beta, the one criticism Gordon did have concerned a degree of HF "sizzle" to its sound, which was present to a greater or lesser degree in all the samples he auditioned. He felt, however, that this seemed to be a function of the EMIT, which covers the region below the one that measured as being too high in level. Certainly, I could hear the measured EHF lift as an added degree of "air" and sparkle, but despite being noticeable, it was not unpleasant. Gordon felt that the samples measured had the least amount of HF sizzle of any he had heard, but listening to music while carrying out these measurements, I was still aware that there was some added brightness in the mid-treble when compared, for example, with the Quad US Monitor. I hoped, therefore, that looking at the speaker's impulse response might indicate the reason for this tonal characteristic, which doesn't seem to correlate with any broad-band amplitude-response problem.

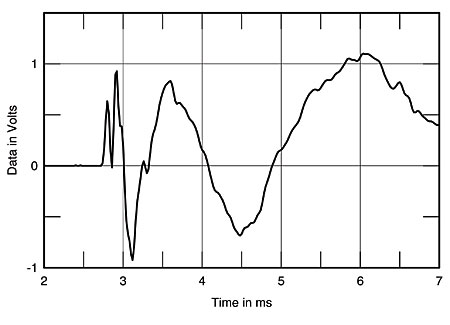

And therein lies the same problem I had with the Quad: I was restricted to a microphone position unreasonably close to the speaker if early room reflections were not to cloud the issue. Fig.4 shows the time response of just the mid/treble panel to a unidirectional, rectangular 55µs pulse taken at a 1m microphone distance. (The window shown covers a 5ms period to reveal as much fine detail as possible.) Compared with the Quad US Monitor, the response is far more complicated, but it must be remembered that we are looking at a multiway design here compared with a single full-range diaphragm, and that the 1m mike distance will not allow the outputs from the individual drivers to integrate as well as they would at a 3m listening distance. The mike here was 39" high on a level with the bottom of the small EMIM unit, representing a typical listening height, directly in front of the panel. The tone controls were set with the EMIT at maximum, the S-EMIT at 9 o'clock and the EMIM at 11 o'clock.

Fig.4 Infinity IRS Beta, impulse response of midrange/treble panel (5ms time window).

Interpretation of the raw pulse shape is difficult, but calculating the step response (fig.5) gives a clear picture. The initial spike of energy is due to the S-EMIT. The second, larger but 100µs later positive spike of energy will be due to the EMIT, which appears, therefore, to be connected in the same acoustic polarity. This has a significant negative-going overshoot, following which is superimposed the rise in energy from the small EMIM, which is not quite time-coincident. The later, slow-rising arrival represent the energy from the large EMIMs. The tail of the step is overlaid with a complex pattern of arrivals and ringing. Though these are well down in level compared with the initial peaks, it is possible, though impossible to say probable, that the "sizzle" complained about by Gordon correlates with the presence of this ringing on transient signals.

Fig.5 Infinity IRS Beta, step response of midrange/treble panel (5ms time window).

Compared with a typical, high-order–crossover, box loudspeaker, the time performance of the Beta is still good, with the bulk of the energy arriving within 1ms. At a more typical listening distance, where the sounds from the five drivers will have had a chance to better integrate, I would expect the Beta to have an excellent subjective transient characteristic, which indeed it does.

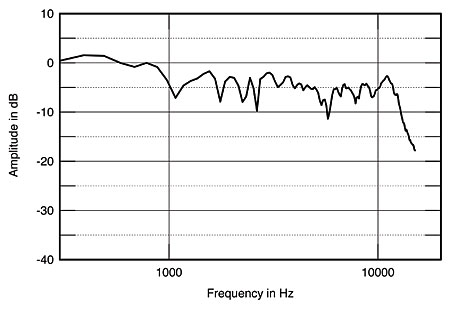

Fig.6 shows the Discrete Fourier Transform (plotted up to 10kHz) of the Beta midrange/treble panel's impulse response (taken under the same conditions as fig.4 but this time over a 10ms time window, which will give 100Hz resolution). Again, interpretation is hardly straightforward, but the overall shape is flat, broken up by what I would imagine are mainly interference phenomena from spaced drive-units carrying the same signal over a significant proportion of the frequency band. The slight lack of energy in the 5–7kHz region is noticeable, however, as is a resonant peak centered on 2950Hz. This latter might well correlate with Gordon's "sizzle."

Fig.6 Infinity IRS Beta, quasi-anechoic response, midrange/treble panel.

Summing-up time: The IRS Beta has many strong points in its favor, including true large-signal 20Hz bass extension, a fundamentally flat tonal balance from the bass to the low treble, a neutral, uncolored midrange, tremendous dynamic range capability, and superb imaging (although, of course, these last two do not reveal themselves in the basic set of measurements carried out). Against these must first be set the difficulty in getting an optimum match between the woofer towers and both the room and the midrange/treble panels (though the excellent range of control options included in the IRS LF crossover unit should mean that any audiophile possessed of patience and hearing acuity should be able eventually to achieve both). Of more seriousness, I feel, are the bright nature to the mid-treble, which seems to be tied in with resonant problems, and the shelved-up nature of the top audio octave, both of which will render the speaker system very sensitive to HF problems elsewhere in the system. As mentioned earlier, the exaggerated top octave is purely a tonal balance problem, which will be considerably ameliorated by using tube amplification, but the former will persistently underlie the music to a greater or lesser degree.

To put this criticism into perspective, I have yet to hear a commercial loudspeaker system that can better the IRS Beta in being able to reproduce the sweep and scale of large-scale classical music with a full 20Hz–20kHz frequency balance. (I don't regard the IRS V and Wilson WAMM as commercial products in the sense that you can just go out on a Saturday afternoon and buy them.) It therefore rightfully claims its place in Class A of Stereophile's "Recommended Components" listing, but those prepared to cough up the five-figure admission to its sound quality should be prepared to spend both a lot of time and attention getting it to sound at its best, and a lot of money on optimizing the components and the listening room. One final point: All my experience with the Beta indicates that it must be listened to from a reasonable distance to enable the sounds from the widely spaced drive-units to properly integrate: at least 3m, 10', in my opinion. If your room does not allow you to sit that far away and allow sufficient space for the speakers to be positioned well away from room boundaries, then the IRS Betas are not for you.—John Atkinson

Footnote 1: Audio Control Industrial SA-3050A 1/3-octave spectrum analyzer with calibrated microphone and integral pink-noise source; Heath/Zenith PC-controlled 8-bit storage 'scope; Fluke 87 true-RMS multimeter; homebrewed computer-controlled sinewave, squarewave, and pulse generators.—John Atkinson

Footnote 2: Individual 1/3-octave response curves are taken for both left and right loudspeakers at 14 positions covering an approximately 8' by 3' spatial "window" centered on the listening position. The curve shown in the figure is the average of these responses, weighted toward the actual listening position. I have found it to give a benchmark response that eliminates the effects of LF room resonances to a large degree, and includes enough of the room sound with that heard direct from the loudspeaker for it to correlate very well with a loudspeaker's subjectively perceived tonal balance. It is not intended to be accurate in absolute terms, but as a consistent basis for comparison with other loudspeakers reviewed in Stereophile, it has proved very reliable.—John Atkinson

- Log in or register to post comments