| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Festival! The Best of the 1995 Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival The Venue & the Concerts

The Venue & the Concerts: Wes Phillips

Footnote 2: The Brahms trio recording was subsequently released on Serenade, which also contains works by Mozart and Dvorák.

St. Francis Auditorium, the venue for these performances, is located within the New Mexico Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe. The structure replicates the New Mexico building at the 1913 Panama California Exposition commemorating the opening of the Panama Canal. Based on the architecture of New Mexico's Spanish missionary churches---such as the Mission Church at Acoma and the San Felipe Church---it is an awe-inspiring adobe structure. The Auditorium resembles a chapel: the ceiling soars some 30' above the pew-style seating and is supported by vigas---exposed cedar posts that run from sidewall to sidewall. Murals on the adobe walls depict the Conversion and Apotheosis of St. Francis, the Vision of Columbus, Preaching to the Mayans and Aztecs, and the Building of New Mexico Missions.

St. Francis Auditorium, the venue for these performances, is located within the New Mexico Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe. The structure replicates the New Mexico building at the 1913 Panama California Exposition commemorating the opening of the Panama Canal. Based on the architecture of New Mexico's Spanish missionary churches---such as the Mission Church at Acoma and the San Felipe Church---it is an awe-inspiring adobe structure. The Auditorium resembles a chapel: the ceiling soars some 30' above the pew-style seating and is supported by vigas---exposed cedar posts that run from sidewall to sidewall. Murals on the adobe walls depict the Conversion and Apotheosis of St. Francis, the Vision of Columbus, Preaching to the Mayans and Aztecs, and the Building of New Mexico Missions.

On July 25th, we entered St. Francis Auditorium to hang the microphones (see John Atkinson's essay on equipment and microphone placement). JA had spent a lot of time in the space, calculating positions and pre-planning the logistics of the endeavor. Adobe chapels do not, as a rule, feature catwalks, so we had to use a funky battery-powered vertical cherry-picker in order to hang our gear from the high ceiling. As JA, Stereophile's Doug Chadwick and David Hendrick, and I stood around dubiously eying each other's girths and calculating terminal velocities for the masses involved, the Chamber Music Festival's resident engineer, Matthew Snyder, graciously volunteered to do the technical vertical work---or maybe he was just concerned over the time factor involved in a pre-concert cleanup.

We all joked about the "glamor" of recording as we stood with arms outstretched to keep cables from tangling, or crawled on hands and knees to tape them to the floor, or climbed up 30' ladders to confirm channel ID. Recording is a funny job---most of it is totally out of your control, and what isn't is really hard work. Yet it is undeniable that we all felt more than a frisson of excitement at our involvement, no matter how mundane our tasks.

The following afternoon, John used an Appalachian Spring rehearsal to set levels and judge the "bloom" of the hall. This last is tricky, since the sound changes radically once the room fills with people. You want to start with a fairly wet acoustic which will dry out with an audience---but how wet? And how can you tell?

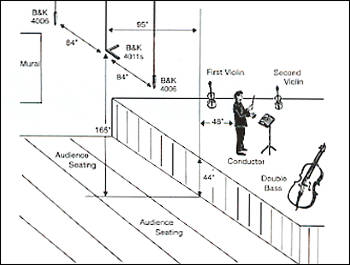

This is where the art resides. I'm sure that some of you have envisioned us creating a grid and then placing our mikes in each possible position for meticulous testing. Perhaps there are engineers who do it that way, but what John did was listen from many, many positions in the hall before making his choices. Additionally, Matt Snyder---who records every performance for the Festival's nationally syndicated radio program---offered a great deal of hard-won advice. For instance, John would have liked to have hung the mikes a little farther out into the hall, but Matt had discovered that those murals, lovely as they are, create a nasty slap-echo that the microphones ruthlessly expose. John opted, instead, for a closer perspective on the musicians.

Microphone positioning used for Festival

Once we hung the mikes, we aimed them by running nylon fishing line back to the balcony, where we tied them off. One of our many visions of disaster concerned an audience member deciding to investigate what was connected to the knots. (John, an inveterate worrier, maintains that this did not happen only because he spent the requisite time agitated over the possibility.) After taping the first rehearsal, John felt that we had erred a tad too far toward dryness and, using the fishing line anchoring the crossed pair, pulled them 12" farther away from the stage and over the audience.

Performances sound brilliant and vivid in St. Francis Auditorium. Articulation is superb, and individual musical lines stand exposed with great clarity. The downside to this is that the hall itself does not generate the sort of mellow "bloom" that distinguishes such revered auditoriums as Carnegie Hall or Boston's Symphony Hall. Yet sound with such clarity of line and brilliant timbre is immensely thrilling. I, for one, found listening to music there a pleasure.

The view from the microphones: the Festival musicians rehearse for the world premiere of Tomiko Kohjiba's The Transmigration of the Soul.

Does this mean that the sound of this disc should be relentlessly "in your face"? Naturally not---these musicians are so much better than that. Just listen to the fat, juicy tone of horn-player Julie Landsman, or flutist Carol Wincenc's feathery flutter-tonguing in the Milhaud, or soprano Kendra Colton's projection in the Kohjiba, and you'll note that when musicians are capable of sonority, strength, or bloom, the St. Francis doesn't mask them---it just doesn't reinforce them with a golden glow as some halls do.

The first night's concert opened with the Copland and was counted a rousing success by everyone involved: players, most definitely the audience---who were on their feet and roaring---as well as John and myself. Through our headsets, it had sounded great. We looked at each other in relief---this was actually going to work!

As the excitement wore off, however, we were left with a long, hard slog: we were present day and night---or so it seemed---recording rehearsals of all four pieces as well as the actual performances. Santa Fe's Spanish Market Festival was going on in the Plaza outside St. Francis, and we discovered that our microphone array was quite good at picking up idling trucks, arguments between festival-goers, and countless other non-musical signals. John's head was frequently in his hands as he agonized over each imperfection. Then there were the coughs, sneezes, rustling candy wrappers, and clanking jewelry during the performances themselves. During one passage of the Kohjiba work, there was so much hacking and worrying of phlegm that I was concerned that the venue might be quarantined as a public health hazard. John's head stayed in his hands for most of this movement, but each new outrage sent convulsive shudders through his frame.

All in all, we recorded a total of four pieces for this disc: in addition to the world premiere performance of Tomiko Kohjiba's The Transmigration of the Soul; Copland's Appalachian Spring (the original version for chamber orchestra), and Milhaud's La Création du Monde, we captured Brahms's Op.40 Trio in E-flat for Piano, Violin, and French Horn on tape. From the start, however, we had planned that this disc would only contain three performances (footnote 2). Recording live, however, imposes certain thrilling constraints upon the technical staff; we just had to have a backup performance. John and Matt traded disaster stories on the afternoon of the first performance: tales of lost tapes, or of engineers who, in playback, discovered they had a reel of blank tape. This may have just been whistling past the graveyard, but I was sweating bullets when the audience quieted and John pressed Record on the Nagra to catch the opening hush of Appalachian Spring.

Our job is over now, but not all of our worrying---hope you enjoy the disc.---Wes Phillips

Footnote 2: The Brahms trio recording was subsequently released on Serenade, which also contains works by Mozart and Dvorák.

- Log in or register to post comments