| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

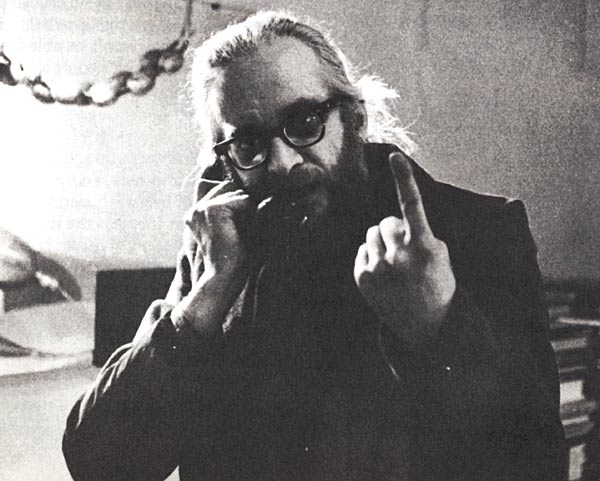

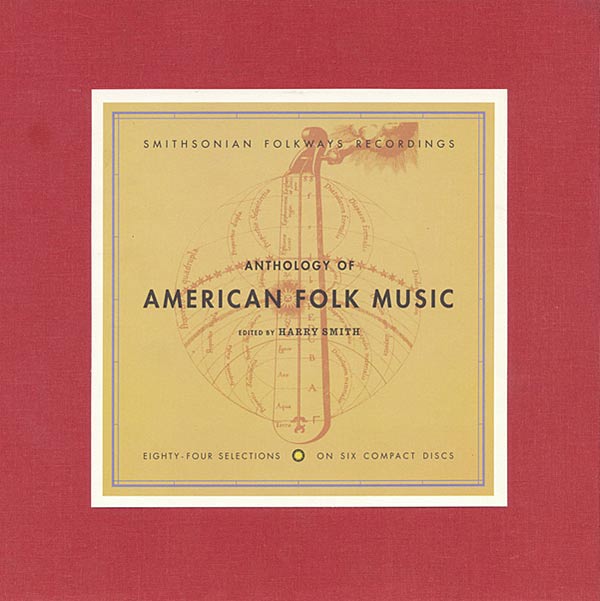

That's a fine piece of writing about a man all music and art-loving humans should venerate. Harry Smith was a man of genius and deep spiritual understanding. Whether we remember or not, Harry's original bootleg anthology dramatically impacted America's postwar music evolution. Even more, Harry Smith's 'abstract' films (and paintings) impacted postwar visual art. I remember watching his groundbreaking hand-painted films in art school. He lived at the Chelsea Hotel until 1977, and showed his films in art galleries and performance spaces in SoHo where I and my friends would hear him speak and show his films 'for a small donation.' He died broke and pretty much homeless.

According to Wiki, at one point, Smith found himself "...living at Francis House, a home for derelicts on the Bowery." Where he continued to tape ambient sounds, including "the dying coughs and prayers of impoverished sick people in adjacent cubicles."

Thank you Sasha for your help keeping his flame burning.

peace love and understanding

herb