| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

George Avakian: That Rhythm Man!

"So where did it all go wrong, George? When did the major-label record business begin slipping away?"

Before he can answer, I recall something George Avakian once told me over the phone. "Goddard Lieberson [former president of Columbia Records] said, 'I'm tired of sitting in A&R meetings with record guys. Get me some lawyers and accountants who don't want to argue about music.'"

"I don't remember saying that, but that's very interesting," Avakian says with a mischievous smile of recognition.

Renowned as a producer and engineer, and the first man to record a collection of songs meant to issued together as an album (as opposed to a series of singles), Avakian, while he worked at Columbia Records, was one of the forces who built what is perhaps the world's largest catalog of recorded music—or, as he puts it, "every aspect of education as well as entertainment for the knowledgeable purchaser." He is also one of the last living links to the pre- rock'n'roll music business, and a time when the major labels thrived as they shifted into high gear during the transition from the 78rpm shellac to the 33.33 long-playing (LP) vinyl disc. He connects back to an era when working at a record label was still about music and musicians, as opposed to manufactured celebrity and entertainers; to the halcyon days when the business of selling recordings was large and profitable. Most famous for the time he spent working first as a freelance producer and, from 1946 to 1958, on staff at Columbia, Avakian is erudite, opinionated, and genial. At 92 he may be a bit more bent over than he used to be, and a touch more forgetful, but he's retained the quick mind and personal verve (to use a jazz word) that have made him such a dominant figure in the history of recorded music.

"This irritates the hell out of me." He points at the cane leaning against his chair. "I can't walk the way I used to; my spine has been shrinking. My driver's license still says 5' 10?, which was what my height was when I was 17. I'm now 5' 3?, the same height as my wife and Louis Armstrong."

As we sit in the living room of Avakian's comfortable home, just north of Manhattan, looking out picture windows at the Hudson River and the green Palisades beyond, the enormity of his career suddenly washes over me. What to ask about first? Miles Davis's 'Round About Midnight? Duke Ellington's Ellington at Newport? Louis Armstrong's Ambassador Satch? What about Paul Desmond, Sonny Rollins, Dave Brubeck, and John Cage, all of whom Avakian also recorded? Best to begin with Avakian's new project, a record with New Orleans master Dr. John. This master of the telling anecdote leans forward and begins.

"That came about in an odd way. A young lady my wife [violinist Anahid Ajemian] and I met in Paris some years ago—Sarah Morro, from Ohio, living in Paris, playing trombone and writing and arranging, and doing pretty well. We liked her so much that we became very good friends, and she started calling us Uncle George and Aunt Anahid, which a lot of young musicians actually tend to do. I think it started down in New Orleans one year, when I ran out of subjects to talk about at the Armstrong Festival and I said, 'Let's just have an "Ask Uncle George."'

"Anyway, she called one day—we hadn't seen her for a couple of years—and said she was in town with Dr. John, playing in his band, they were going to appear at the Apollo Theater, and Mac [Rebennack, aka Dr. John] wanted to see me again. We hadn't seen each other in years. I said, 'Sure, come on up to the house.' By the time he got to the front door, the idea hit me: Dr. John Meets Louis Armstrong, one extreme of the New Orleans spectrum and the other. What would happen if Mac did Armstrong repertoire in his own way? We're finding out."

In April, just before the annual Satchmo SummerFest, when Rebennack's tour schedule brought him home to play, Dr. John and Avakian had their first recording session in New Orleans, at the Music Shed Studios, with Avakian producing. Avakian says that half the album is done, and while Rebennack prefers to record "in layers," (overdubbing) an approach that Avakian doesn't like, he says that in this case it seems to be working. While he likes what's been committed to tape so far, Avakian, always an idea man—not to mention Armstrong's longtime producer and friend—clearly relished choosing the songs.

"I gave [Rebennack] a list of about 21 compositions to choose from. He came up with some that I hadn't thought of which were very good choices. And I've thought of others since. I don't know what we're going to do in the next session. Mac surprised me by wanting to do 'What a Wonderful World,' which I thought was a cliché, but he has an unusual twist on some of the things. He shocked me by doing a tango version of one of the compositions, 'Tight Like This.' It resembles 'St. James Infirmary.' It's very down and rough, tough, and so forth, but he turned it into a tango, and it works. Amazing."

Avakian says that, unlike a lot of New Orleans recording studios, which he calls "primitive and rudimentary," the Music Shed is first class. "Sound is always the heart and soul of recording, because if you haven't got an accurate depiction of the sound that is actually performed in a live performance . . . there is a quality that is kind of phony, I feel. I've felt very badly about all the recordings that were made with gimmicks, but that's the way the pop business went. I'm glad that the quality of sound has gotten so that people respect it for what it is. In the old days, I don't think people gave that much attention to purity of sound because the emphasis was on the content of the music, whether it was directed at the pop market or what . . . "

Avakian smiles and admits that he tends to ramble; at several points he good-naturedly exhorts me: "Steer me! Keep me on track!"—and often follows the answer to a question with a priceless anecdote.

"One of the astounding things that I found was when I started putting old masters out on LP, the best way was to find the original metal parts and play the part itself, or a vinyl test pressing made from it. We discovered that the recording techniques from the '20s and '30s were such that much more information was put on the masters than could be brought out by the pickups and playback equipment [of that time]. When I did the Bix Beiderbecke reissues on LP, I was stunned by the fact that his sound was even more exciting and more Bix-ian, shall we say, than I had realized. And just for fun, one thing I did also, which some people thought was sacrilegious, I added a slight touch of echo to some of these old masters, because they were made in such dead, small studios. When I was doing the Bix LP reissues [The Bix Beiderbecke Story, Vols. 1–3, Columbia], I told the engineer, 'Let's throw some echo on this.' The one I used was 'Jazz Me Blues,' I think, one of the brighter Bix performances. That wonderful bell-like sound that he had—put the echo on it and you really have Harry James with echo chamber in Liederkranz Hall!" (Liederkranz was the site of many Columbia recording sessions. The building still stands, at 111 E. 58th Street, between Park and Lexington Avenues in Manhattan.)

"One of the astounding things that I found was when I started putting old masters out on LP, the best way was to find the original metal parts and play the part itself, or a vinyl test pressing made from it. We discovered that the recording techniques from the '20s and '30s were such that much more information was put on the masters than could be brought out by the pickups and playback equipment [of that time]. When I did the Bix Beiderbecke reissues on LP, I was stunned by the fact that his sound was even more exciting and more Bix-ian, shall we say, than I had realized. And just for fun, one thing I did also, which some people thought was sacrilegious, I added a slight touch of echo to some of these old masters, because they were made in such dead, small studios. When I was doing the Bix LP reissues [The Bix Beiderbecke Story, Vols. 1–3, Columbia], I told the engineer, 'Let's throw some echo on this.' The one I used was 'Jazz Me Blues,' I think, one of the brighter Bix performances. That wonderful bell-like sound that he had—put the echo on it and you really have Harry James with echo chamber in Liederkranz Hall!" (Liederkranz was the site of many Columbia recording sessions. The building still stands, at 111 E. 58th Street, between Park and Lexington Avenues in Manhattan.)

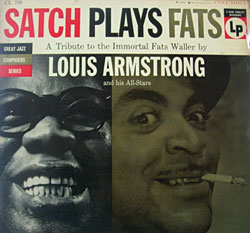

Asked what records he's most proud of in his illustrious career Avakian gestures toward two LPs I've propped up on the couch next to me: Louis Armstrong's Satch Plays W.C. Handy (1954) and Satch Plays Fats (1955).

- Log in or register to post comments