| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

George Avakian: That Rhythm Man! Page 2

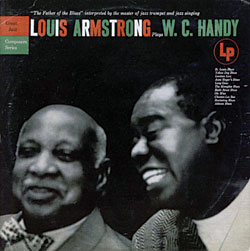

"Those two albums got a tremendous reaction. I was kinda proud that Wynton Marsalis said that these were the best recordings that Armstrong had made since the 1930s—because they really are! Part of that is the subject material. When I got a chance to record Armstrong, I already knew what I wanted to do for the first three or four albums. We had talked about it, because he had befriended me in . . . well, that would be about 19 . . . let's see, it had to be whenever I found those unreleased Hot Fives and Hot Sevens [which Columbia released on 78s]. I was in college as a sophomore, so that would be '38, '39 . . . actually, 1940 probably, early. Somehow, nobody'd ever thought of doing an album of Handy's blues. One problem, of course, is that he didn't write that many that were really good. He had a few successes after 'St. Louis Blues,' but what we recorded is just about the best of it.

"I've told this story before, but the night I went backstage at the Apollo Theater and Pops said, 'Let's go get some ice cream and go over to my darling's,' I didn't know who his darling was. It turned out to be Lucille [Wilson, whom Armstrong married in October 1942]. We went to Lucille's mother's apartment, in Harlem. I parked my roommate's car out front. It was a gorgeous night, moonlit, not a cloud in the sky. As we left, he stopped on the steps of the apartment building. I wondered, 'What happened to Pops? He's not next to me.' I looked back, and there he is, standing on the steps, with his arms raised, looking at the moon and doing a pirouette, and saying, 'My darling, my darling, isn't she wonderful?' And I thought, 'My God, Louis Armstrong, my hero, is exposing his innermost soul to me!' I felt the relationship was at a new level, and so it was—because from that time on, whenever Pops had some time off, he'd call me up and say, 'Come on over to the house and just sit around and talk.' And these albums grew out of those conversations."

"I've told this story before, but the night I went backstage at the Apollo Theater and Pops said, 'Let's go get some ice cream and go over to my darling's,' I didn't know who his darling was. It turned out to be Lucille [Wilson, whom Armstrong married in October 1942]. We went to Lucille's mother's apartment, in Harlem. I parked my roommate's car out front. It was a gorgeous night, moonlit, not a cloud in the sky. As we left, he stopped on the steps of the apartment building. I wondered, 'What happened to Pops? He's not next to me.' I looked back, and there he is, standing on the steps, with his arms raised, looking at the moon and doing a pirouette, and saying, 'My darling, my darling, isn't she wonderful?' And I thought, 'My God, Louis Armstrong, my hero, is exposing his innermost soul to me!' I felt the relationship was at a new level, and so it was—because from that time on, whenever Pops had some time off, he'd call me up and say, 'Come on over to the house and just sit around and talk.' And these albums grew out of those conversations."

Which of the two does Avakian think works best? "I think the Handy; the material is better because it's not just pop songs. And yet, two or three of the songs that [Fats] Waller and [Andy] Razaf did are magnificent. And with Waller, he and Pops, they were the two bad boys of the period. They tore up Harlem something badly."

In 1990, Columbia, as part of its Jazz Masterpieces reissue series, reissued Satch Plays Fats and Satch Plays W.C. Handy in radically altered forms, with new cover art, and substituting previously unreleased alternate takes for the master takes chosen for the original editions. In many cases—such as "Ain't Misbehavin,'" from Satch Plays Fats, in which the lightning-fast issued original take features Armstrong singing so fast that his words literally run together, the alternate is clearly inferior.

"I never talked to the producers, but they were nice people, I think," Avakian says. "I think they got carried away with hearing the unreleased material. That's something you have to treat with great care. Just being able to put out an alternate take is not the answer to wanting to put it out. I don't think they played around that much with the sound, but I still like the original sound best. One of the problems I've found is that, with younger engineers, they're dying to show what they know, and . . .

"When I was recording Keith Jarrett [whom Avakian managed in the early 1970s] at the newer Columbia studios, on 52nd Street [CBS Studio Building, 49 E. 52nd, Manhattan], a young engineer came in from next door and listened to the playbacks [for the 1972 album, Expectations]. I was sitting down at the bottom and Keith was up on top with the engineer, and I said, 'Keith, I think that's okay; should we continue?' He said, 'Sure,' and he walked out. The young engineer looked at me—an old man, of course [points at himself]—and said, 'Are you producing this session?' And I said, 'Yes, I am.' He said, 'Well, how many tracks are you using?' I said, 'Gee, I don't know, I think maybe four or five.' He said, 'How come you don't use more?' And I said, 'Well, I don't need them. I don't even need those. I only have eight or nine musicians out there.' And he made some kind of remark about that being extraordinary, so I thought I'd lay something on him: 'Well, what if you had to produce the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Philadelphia Orchestra with [Eugene] Ormandy conducting—that's about 200 people—and you weren't allowed to make any splices?' He laughed, and then he stopped and looked at me and [said], 'You mean mono?' And I said, 'Yes.' He said, 'You mean you did that?' And I said, 'No, I never did use that many musicians, but that's the way we worked: no splicing, no nothing.' He shook his head and walked out, saying, 'Man, you cats was braaavvve!' What a line!"

Another trumpeter, whom Avakian signed to a recording contract at Columbia and then, as with Armstrong, grew personally close to, was Miles Davis. "Miles was a very layered person. He put up walls between you, and then he invented himself this way and that."

Does it surprise Avakian that Miles has become one of the most toweringly influential figures in jazz history?

"It does indeed, because I thought Miles's greatest potential, outside being recognized as a jazz performer, was as a ballad performer. I thought he was the greatest ballad interpreter since Louis Armstrong, and he is. People ignore the beauty of [Davis's versions of] Gershwin and the American Songbook performances: 'But Not for Me,' stuff like that, it's gorgeous, terrific. And I didn't realize that he would have the appeal on the so-called avant-garde jazz level. And I think it's a pity, in a way, because it took away from the other qualities he had. By the time he was in his electric period, I thought the music was pretty stagnant and uninteresting. I don't enjoy those long endless things—which Miles complained to [John] Coltrane about. Coltrane said, 'I can't find a way to stop,' and Miles said, 'Did you ever think about taking the horn out of your mouth?' Greatest remark of all time.

"The biggest surprise to me was Kind of Blue [1959]. That grew out of a conversation that I had with him once . . . I was very close, through my wife and her sister, with the avant-garde composers, so-called, like John Cage. I told Miles about taking Cage and [choreographer] Merce Cunningham to hear the Bunk Johnson Band when they were appearing at Stuyvesant Casino [at 140 Second Avenue in Manhattan; now defunct]. Cage's reaction was, 'My God, these musicians are marvelous, but why do they bother with the bass, drums, and piano? They should be three horns improvising with no accompaniment.' I think that was the starting point of conversations with Miles that led to the, how should we say, 'no theme' aspect of Kind of Blue. He didn't express it that way, but when I heard the first takes of what he was doing—which was after I left, but he played it for me at his house—I realized that that's what began the thinking. And he even said that he could have done it without a rhythm section—maybe. He wouldn't say that they could have, but the thread was there."

As so often in our conversation, this story triggered another.

"When Gunther Schuller recorded his Symphony for Brass and Percussion, Op.16 [on the Columbia album Music for Brass, 1957], and on the other side of the record were three compositions by jazz players [John Lewis, J.J. Johnson, and Jimmy Giuffre], he asked me if I thought Miles would be willing to play the flugelhorn solos that were in the [other] scores. I asked Miles, and he said he would. He borrowed a flugelhorn from Clark Terry, his mentor. I thought it would be interesting for Miles to come and see, hear what was being done on the symphony side of the record with [Dimitri] Mitropoulos conducting [the New York Philharmonic]. At the end of the first take, Miles tugged at me and said [in a dead-on impression of Davis's gravelly voice], 'You think he'll let me play with this band some time?' I said, 'I'll ask him.'

"At the next break, Miles is sitting there in the control room, and at the end of listening to it I said to Mitropoulos, 'Maestro, this young man is going to play trumpet on the other side of the record, and he's very, very good, and he hopes some time he might play with the Philharmonic.' Mitropoulos was terrific. What a man! He bowed to Miles. He bowed to me. And said, 'Yes, perhaps,' and walked out. Miles was smart enough to never say a single word [about it] ever again. That was part of Miles's astuteness. He was a hell of a lot smarter than all of us put together. Creating his persona—which was not real, and yet it was, in a way—it was just an exaggeration of a minor side of Miles. Miles was a very mild-mannered, nice young man, a very straightforward ordinary person deep inside—and then came the huge success."

Crusty, and yet still able to discuss the music of Lady Gaga ("It's totally ludicrous!"), Avakian has found that one of the advantages of longevity is having the last word. Ever the renaissance man, Avakian, in remembering his days at Columbia, even manages to slip in a quote from a famous speech by Orson Welles in the 1949 film The Third Man.

"Goddard [Lieberson] was not a nice person—you've heard that, I'm sure, from many people. Self-centered. His idea of being the president of Columbia was mainly inviting Noâl Coward to lunch. But he sure had a great staff under him. There were about six people who did everything. And now they have a whole building full of people, and they've had that for 30 years, and what came out? The cuckoo clock!"

- Log in or register to post comments