| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The Fifth Element #92 Page 2

I checked the bass-extension claim by listening to the "Full Glide Tone" from Ayre Acoustics' Irrational, But Efficacious! System Enhancement Disc, Version 1.2. At the moment in the tone's sweep upward—it starts at 4Hz—when I believed that the Square One's woofer was actually producing "tone" and not just fecklessly flopping, I hit Pause on the Parasound Halo CD 1's remote control, noted the elapsed time on the CD 1's display, and, using the Amadeus Pro II app, opened the "Full Glide Tone" digital-audio .wav file, and captured a small sample that included about one second to either side of the indicated time. From the "Analyze" pull-down menu I selected "Spectrum." The spectrum I obtained was centered on 44.1Hz. Keeping in mind unavoidable experimental error, I find WB's claim of 45Hz credible—and very impressive for a speaker with an internal volume of only 10 liters.

Footnote 2: Paul Weston's stage name, Jonathan Edwards, was perhaps the ultimate musicians' inside joke. öbersuccessful lounge pianist Louis Jacob Weertz took as his stage name Roger Williams, the name of the 17th-century Baptist theologian of Rhode Island. Therefore, at the suggestion of Columbia Records producer George Avakian, Weston took the name of Jonathan Edwards, an 18th-century Calvinist from Connecticut. (The 1970s singer-songwriter Jonathan Edwards apparently came by his name honestly.)

Listening

For all of my listening, the source (and volume control) was Bricasti's M1 DAC, fed either by Parasound's bombproof Halo CD 1 as a transport, or from my iMac running Audirvana Plus. Cardas Clear balanced or single-ended interconnects linked the Bricasti M1 to one of the three power amplifiers I used: Channel Islands Audio's E•200S (200Wpc), and Luxman's M-600A (30Wpc, class-A only) and M-700u (120Wpc, class-A/B), all reviewed in the June "Fifth Element."

My review samples of the Square Ones had come from a dealer's showroom floor. Even so, they required a certain amount of break-in (or re-break-in). The rear-mounted ABR's inverted surround was very stiff. Even very loud music with significant bass content didn't cause large excursions.

Wilson Benesch does not state a minimum recommended amplifier power, but, with its ABR and claimed 87dB sensitivity—and its characteristic WB trait of favoring bass quality over bass quantity (or extension)—I'd say that 50W would be the bare minimum, and that the amplifier should have great current drive and exemplary damping factor. Doubtless a safer bet would be 100Wpc. Luxman's M-600A (30Wpc) just could not deliver the goods to the Square Ones. But when I switched to the slightly more "modern"-sounding M-700u (120Wpc; see my June 2015 column), what I heard sounded almost like another full octave of bass extension.

In among all that, I experimented with positioning. I moved the Square Ones closer to the front wall than I've placed most speakers in my room, which firmed up the bass without causing any bothersome side effects. I ended up with the Square Ones completely toed in to the listening position, and with the center of each rear panel 12" from the wall behind it. Placing each speaker a third of the way along the front wall made the distance between the centers of the front panels about 5.5', and resulted in the speakers and listening position describing a slightly elongated isosceles triangle.

The opening movement, Trauermarsch, of Mahler's Symphony 5, from Eliahu Inbal's underrated (I think) recording with the Frankfurt RSO (CD, Denon CO79737), had startling dynamics and amazing depth of soundstage, the brasses and percussion sounding surprisingly powerful for a speaker of so small a footprint. That said, while there was a suggestion of bass impact, there wasn't much slam. (One workaround would be to partner the Square Ones with Wilson Benesch's Torus, a passive subwoofer with vertically firing, 18" driver: $6730.)

Standard audio reference recordings of female voices—eg, Jennifer Warnes on her Famous Blue Raincoat: The Songs of Leonard Cohen (CD, Attic ACD-1227), and Margo Timmins in "To Love Is to Bury," from the Cowboy Junkies' The Trinity Session (CD, RCA/Classic RTHCD8568)—were as plangent and as emotionally engaging as I have ever heard them, with, again, remarkable depth of soundstage.

A rare find indeed is an almost-unknown French-Swiss recording of a Tommy Flanagan New York City studio date from 1993, Lady Be Good . . . For Ella, with bassist Peter Washington and drummer Lewis Nash (CD, Groovin' High 521 617-2). Flanagan spent many years as Fitzgerald's music director, and all of the songs here are associated with or at least reminiscent of her. For what it is—a multimiked studio recording with an arbitrary stereo perspective—it's a fabulous recording. The playing is soulful, in places elegiac. It took me a while to figure out that Flanagan's slow solo-piano intro to the first of two iterations of "Oh, Lady Be Good!" fit the words to the nursery rhyme "Mary Had a Little Lamb." A message in a bottle, perhaps?

The Square Ones were the perfect match for this music. Their soundstaging abilities made the studio's sound larger and freer, while the music's bass demands didn't outrun the speakers' bass capabilities. The clarity of the sound of Flanagan's piano was exemplary. While the Square One didn't sound "analytical," it also didn't sound like a traditional British BBC-heritage loudspeaker, by which I mean a tailored frequency response with midrange warmth on almost all recordings.

Back to Mahler, this time Des Knaben Wunderhorn, for mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly's luminous, nearly heartbreaking "Urlicht" in the recording by Philippe Herreweghe directing the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées (CD, Harmonia Mundi 901920). Yes, the Historically Informed Performance Practices crowd has caught up with Mahler (though despite the claim of period instruments, A is here 440Hz, not 432Hz). Fear not—it's a stupendous performance. It sounded stunning through the Square Ones, in part because this is the Gustav Mahler of dimly remembered Lutheran chorales played by brass choirs, without any huge side-drum thwacks. Given the Square One's rather high crossover frequency of 5kHz—an octave higher than the norm—I kept listening for some discontinuity between midrange and treble, but heard none. In my estimate, Connolly's performance is as treasurable as Anne Sophie von Otter's. And what a way to end a listening session!

The Square Ones are a premium-priced product, to be sure. However, they have much of the same technology and the same build quality as Wilson Benesch's more expensive models, and provide a smaller-scaled version of WB's house sound: "extremely low distortion, seamless coherence, unfussy easefulness, rounded liquidity of tone, articulate dynamics, and seductively natural imaging and soundstaging." The price tier of ca $5000/pair (including stands) is crowded and competitive, but the Square One is a standout performer that I think absolutely deserves a very high Class B (Restricted LF) rating in our "Recommended Components." It very well may be over the line into Class A (Restricted Extreme LF) . . . but John Atkinson will have to decide that after I have sent them to him for measurement.

Jazz Rediscovery of the Decade

Purely by chance, I came across a used CD: Jo + Jazz, featuring Jo Stafford (1917–2008), a once-famous singer whose career began in the 1930s, and whose unstinting service entertaining military personnel during WWII earned her the nickname "GI Jo."

Stafford and her husband, the arranger Paul Weston (1912–1996), later became famous for their comedy act Jonathan and Darlene (footnote 2), in which Weston played the piano as though he had two right hands, and Stafford, a trained singer, sang perfectly off-pitch. When I glanced at the recording date for Jo + Jazz, I was surprised. I had thought that, by 1960, Stafford was no longer making serious records.

A closer examination left me fairly agog. The list of assisting musicians is stellar: Ben Webster, Johnny Hodges, Ray Nance, Jimmy Rowles, Mel Lewis, Conte Candoli, Russ Freeman, Don Fagerquist. Orchestrations were by Johnny Mandel, from the time before he struck pay dirt with "The Shadow of Your Smile." Jo + Jazz was recorded just 16 months after Kind of Blue, in the same studio, with the same producer—Irving Townsend—and (I must assume) the same equipment and engineers. Remarkable! Why had I never heard of this?

The CD I discovered was from a label I'd never heard of, Corinthian Records, but Jo + Jazz was originally released by Columbia, and therein lies a tale. Despite some truly arresting singing, and great arrangements played by a phalanx of legendary musicians, Jo + Jazz seems to have been a flop. Stafford and Weston reportedly thought that Columbia failed to promote the record adequately. That might have been the case. But, in the label's defense, tasteful jazz singing was going begging in 1960, the year of "Yellow Polka-Dot Bikini," with top chart positions going to Elvis Presley, Chubby Checker, the Drifters, and a strong showing for Ferrante & Teicher's "Theme from Exodus."

Weston and Stafford eventually acquired the rights to the master tapes, and reissued the LP. (The Corinthian reissue and original Columbia LPs are often on eBay.) Their son Tim Weston, working with engineer Roger Nichols (1944–2011), of Steely Dan fame (footnote 3), later remastered the project for re-reissue, and a darn good-sounding CD it is (Corinthian COR 108CD). The two standout cuts are "The Folks Who Live on the Hill" (Stafford's is now my go-to version) and "Imagination," but the entire album is a treat: a precious moment in time forever frozen in amber. I played some tracks for speaker designer Winslow Burhoe and his wife, and Burhoe remarked on the recording's excellent dynamic range. Yes indeed.

The remastered CD is available from Amazon.com for $12.99; the price includes a free MP3 rip. What's not to love?

Lollipops Beyond Delightful

Composer Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) was also a pianist and a string player. He played viola in the orchestra of Russian Imperial Theater in Saint Petersburg during the seasons of Italian opera there, and later played first violin in an Italian string quartet. During Respighi's formative years, the musical life of Italy was "all opera, all the time." However, during Respighi's sojourn in Russia, he became a composition student of Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov's, from whom he learned the power of orchestration.

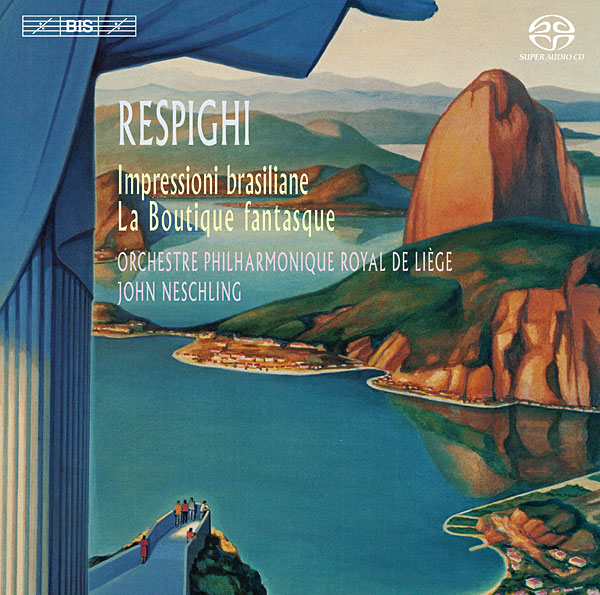

Respighi's fame rests on his Roman Trilogy of orchestral sketches: Pines of Rome, Fountains of Rome, and Feste Romane, recordings of all of which have been longtime audiophile favorites. I saw a favorable notice of a recent Respighi recording by an orchestra unfamiliar to me, Belgium's Liège Royal Philharmonic, and a conductor I'd barely heard of, John Neschling, who turns out to be a grandnephew of Arnold Schoenberg's. The music, too, was less than familiar; I'd never owned a recording of either Impressioni Brasiliane or La Boutique fantasque, the latter Respighi's ballet score based on Rossini tunes. So I requested a review copy (SACD/CD, BIS 2050).

Well, SACD fans, it's again time to vote with your wallets. The sound is beyond stupendous—the crystalline triangle strokes in Notte Tropicale, from Brazilian Impressions, just float, shimmering above the atmospheric strings. The Liège orchestra sounds like a world-class ensemble, aided no doubt by its beautifully preserved, Italianate-Eclectic/beaux-arts Philharmonic Hall, built in 1887. I cheerfully admit, however, that my impressions of the sound are dependent on Respighi's magical evocation of Rio de Janeiro at twilight—all sinuous, airy, impressionistic suggestions and pastel colorings. Beethoven from the heaven-storming end of the dynamic range Notte Tropicale is not.

Neschling grew up in Brazil, and I can't imagine more polished, more idiomatic performances of this music—or more vivid sound. If you love Pines, Fountains, or Festivals, you owe it to yourself to grab this SACD/CD.

Footnote 2: Paul Weston's stage name, Jonathan Edwards, was perhaps the ultimate musicians' inside joke. öbersuccessful lounge pianist Louis Jacob Weertz took as his stage name Roger Williams, the name of the 17th-century Baptist theologian of Rhode Island. Therefore, at the suggestion of Columbia Records producer George Avakian, Weston took the name of Jonathan Edwards, an 18th-century Calvinist from Connecticut. (The 1970s singer-songwriter Jonathan Edwards apparently came by his name honestly.)

Footnote 3: Roger Nichols had a fascinating career. In college, he studied nuclear physics. Later, his day job was in a nuclear power station, but he moonlighted in a studio he and a friend had built in a four-car garage. They took whatever work was available, including radio commercials. Nichols may have been the first to record Karen Carpenter, whom he used for voiceovers.

- Log in or register to post comments