| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I love when you review things I already own. The V-LPS was definitely the most phono stage I could afford, and I have been so impressed with its performance over the built-in stage in my receiver. I got to upgrade the power supply a few months later, but I used a Pyramid PS-3KX for $30--talk about affordable audio, and it made an enormous difference in soundstage depth and sibilant distortion (which I've been fighting consistently since getting into vinyl three years ago). Based on my research before buying and my own experience, I think MF's audience is, indeed, young budget-conscious audiophiles like myself. And if that wasn't their original audience, it's the one that has met them.

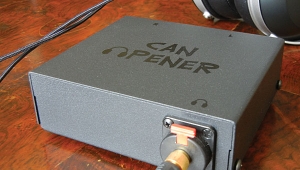

I sympathize with the difficulty of placing the stage, though. It had to go on top of my receiver at an odd angle, then, when I was first listening, I was annoyed by an audible buzz. Moving the box around led to increases and decreases in the buzz, which I haven't enough electrical knowhow to explain--I just found the least awkward possible position with no noise and threw my hands up, vowing never to move it again!