| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

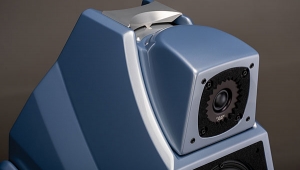

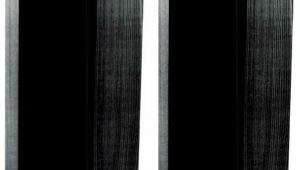

Dynaudio Contour 3.3 loudspeaker Page 3

But to emphasize how natural and extended the tweeter was is perhaps to make too little of the superb balance of the speaker as a whole. The midrange sounded liquid and absolutely free from grain, while the bass was taut, well-controlled, and punchy.

Some might find the Dynaudio's bass quite lean, and it was somewhat. But it was also absolutely free from bloat and overhang—so much so that some listeners might miss just how deep and solid the bass response truly was. I side with Goldilocks: I do not favor a sound either too lean or too loose and flabby. If the Contour 3.3 wasn't just right, it was plenty close enough.

Listening to BMG's UV22 Super CD Encoded reissue of the Reiner/CSO Scheherazade (68168-2), I was struck by how physical the bass-drum rolls seemed in the final movement's shipwreck. And yet they did not overwhelm the hall or the orchestra, but were one element among many—while the Dynaudios gave them their due, it was not at any cost to the rest of the music.

When audiophiles get too caught up in soundstaging, we tend to blur the distinction between the seen and the heard. If you fill a space with objects, one tends to obscure another; but when you fill a space with sounds, this doesn't happen. No matter how full an acoustic space might be, as you continue to stack sound upon sound you will merely be adding more elements to the mix, without necessarily obscuring any of them.

The Contour 3.3s reinforced this lesson upon me time and time again. They projected as physical a soundstage as I've ever heard, although one that existed almost entirely between the two speakers—but no matter how packed it seemed, it remained open and capable of supporting each new instrument upon its entrance.

Take Mighty Sam McClain's XRCD Give It Up to Love (JVCXR-0012-2), for instance. With Sam's deep singing, Kevin Barry's stinging guitar, Lorne Entress' solid drumming, and Michael Rivard's nail-it-to-the-floor bass, you wouldn't think there was room for more in the mix. But Bruce Katz's piano and wonderful B-3 work are easily accommodated in the swelling chorus—and as dense as all that sounds, the Contours had the dynamic ease to accept that crescendo on top of the music's already high levels.

Actually, the Contour 3.3s were as dynamic as all get out, although I did have to goose 'em a little. They really opened up on the slightly loud side of realistic. This didn't mean they always had to be played loudly, but they sounded best when most realistically playing at, or near, the level of the original event. This is not uncommon—no less an audio philosopher than Quad's Peter Walker has stated that there is only one realistic loudness for each disc, and that is the one that most closely approximates that of the original recorded event. Still, many of us listen to music at times, or in situations, where that is not possible; when I turned the Dynaudios down, I was always conscious of something gone missing. But this was a small price to pay for the level of performance they were capable of at their best.

All too frequently, we audiophiles praise a component as neutral by way of damning it with the faintest of praise. "It doesn't add anything," we seem to be saying, "but something's missing." Like, perhaps, the music. This was most emphatically not true of the Contour 3.3. In addition to its finely nuanced presentation of swing, it was a champeen at revealing the emotional text (and subtext) of the musical event.

"Words are really beautiful," Jeff Buckley once said, "but they are limited... The voice comes from a part of you that just knows and expresses and is. I need to inhabit every bit of a lyric, or else I can't bring the song to you—or else, it's just words." On his ethereally beautiful reading of Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" (Grace, Columbia CK 57528), Buckley inhabits every inch of the lyric—a meditation on music and passion. This isn't, in many ways, an audiophile recording; it's unadorned live sound, down to the guitar amp's 60-cycle ground hum. There's tape hiss, too. But through the Contour 3.3s there was something else—I heard the singer's pain, and his redemption too. For six minutes, Buckley inhabited the room. It was chilling and uplifting. But it wasn't magic, it was resolution.

It is not what the speaker says, but who he is, that gives weight to eloquence.—Euripides

At $7000/pair, the Dynaudio Contour 3.3 is not an inexpensive loudspeaker. But it's so natural throughout most of its frequency range that it deserves to be auditioned by anyone listening for a high-end reference monitor. In that context, it might even be considered a bargain.

It does require an amp capable of seizing control over it, preferably at least 100Wpc, but it should surprise no one that a speaker capable of superior performance requires high-quality associated components. And not everyone will be please with the leanish—but, I maintain, quite accurate—bass character, or the speaker's tendency to close down at lower sound levels.

The Dynaudio Contour 3.3 does so much right that it's joined a handful of loudspeaker designs I consider truly special. Its balance of strengths—tonal neutrality, dynamic expression, and taut, unexaggerated bottom end—is so in keeping with my sensibilities that I could happily stop reviewing and settle down with a pair—if not for life, then for a long, very happy exploration of my record collection. You might consider doing the same.

- Log in or register to post comments