| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

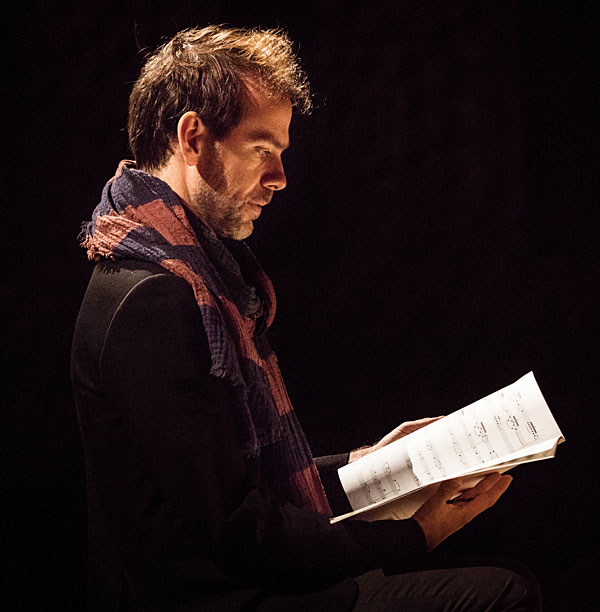

Bryce Dessner: Crossing Boundaries

Photo: Graham MacIndoe

Crossing borders and genre boundaries is never easy, but for Bryce Dessner, it's become a familiar experience.

Dessner, 45, a classically trained guitarist, multi-instrumentalist, and composer, has racked up multi-hyphenates over the last couple of decades of his musical career. Arguably best known for his work with indie rock band The National—where he shares lead guitar, piano, songwriting, and other duties with his identical-twin brother Aaron—he's also an accomplished arranger and producer and cofounder of two record labels.

He's also one of those rare musicians who have authentically crossed—and blurred—the lines between classical music and pop/rock. In a recent phone conversation, we discussed his recent projects, his process, and—of course—music.

Dessner has been working remotely on projects predating the pandemic and also on new collaborations. He's used to traveling as he works and working as he travels. He writes and composes music while touring with The National—or did until COVID-19 put a temporary end to that. He's pressed on.

Dessner is American, but he's been living in Paris for the last handful of years, and he recently moved to the countryside. When we spoke in April, the City of Lights had just entered another lockdown, the pandemic dragging on. For Dessner, as for many, this springtime in Paris hasn't been like others. "I haven't seen my band in a year and a half," he laments. "I haven't seen my brother in a year and a half." These haven't been easy times. But unexpected opportunities have arisen. He and his brother have been working together at a distance—on Taylor Swift's Folklore, to name one project, which won a 2021 Grammy for Album of the Year. Aaron produced and cowrote songs; Bryce arranged the orchestrations.

Dessner thrives on collaboration, "whether it be [with] great performers or other singers or creators or visual artists or dancers and choreographers or filmmakers." He has worked with composers Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Sufjan Stevens, Caroline Shaw, and Jonny Greenwood (Radiohead), pianists Katia and Marielle Labèque, and Icelandic performance artist Ragnar Kjartansson. Composition commissions have come from the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (for the New York Philharmonic), BAM Next Wave Festival, Edinburgh International Festival, Carnegie Hall, Eighth Blackbird, and So Percussion.

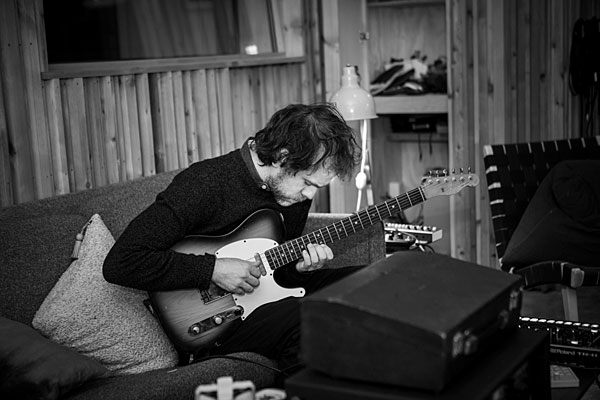

Photo: Peter Hundert

Dessner recently released Impermanance/Disintegration, an album of music he composed for the Sydney Dance Company—the score for their contemporary dance piece titled Impermanance—performed by the Australian String Quartet.

This isn't Dessner's first experience scoring a dance work. In 2016, the New York City Ballet premiered The Most Incredible Thing, choreographed by Justin Peck to Dessner's original music.

Music and dance go hand-in-hand: Dancers dance to music; music responds to dance, if it's allowed to. That's one of the reasons Dessner was drawn to it. "I grew up seeing my sister dance a lot, and so a lot of my early experience is going to see modern dance. And so I have a long relationship with it as an art form.

"I do think one of the great collaborations is between choreographers and composers. And in fact, a lot of my favorite classical music was written for dance—Stravinsky's Rite of Spring or Tchaikovsky's ballets," he said. "There are so many fantastic pieces of music that have been written for dance. So, yeah, I find it very inspiring."

"The dancers have a beautifully physical and emotional response to music, which is really inspiring and kind of freeing for a composer," he told me. "The purely concert works, especially in an orchestral setting, can be a bit more intellectual sometimes than that [dance] environment tends to be." Music for dance "is kind of disarming because you're always thinking about the body and moving and, you know, what do you want to move to?"

Dessner said Sydney Dance Company Artistic Director Rafael Bonachela gave him "a lot of leeway," even allowing him to choose the theme and name the work. He was commissioned to create the score prior to the pandemic. Australia's 2019 wildfires provided themes for Impermanence/Disintegration.

Because of the pandemic, he wasn't able to be there in person with the Australian String Quartet or the dancers. But Dessner had met the Sydney Dance Company in 2015, when he saw them perform a piece choreographed to a string quartet he'd written for Kronos Quartet, so he knew the dancers. "You think of writing for specific musicians," he said. "This is kind of written for specific dancers."

Describing the music's style, he said, "It loosely divides itself into moments of stillness and of loss, and requiem and mourning for things lost with the planet, or for relationships or whatever it is, and then moments of urgency and more frenetic type of sound." The album closes with "Another World," a new version of English musical artist Anohni's haunting song steeped in rich, soulful vocals. Dessner got Anohni's permission to include and rework the original 2008 track with a new arrangement including strings.

Working at a distance impacted the process. "I think it's been a very difficult time for performers, for creators and people who are doing more in the composition or engineering side," he said. "It's been interesting learning how to collaborate from afar."

He was able to monitor the Australians' rehearsals remotely and to "attend" the dress rehearsal via Zoom, "with decent audio," he told me. Dessner told me he has never met the ASQ, and yet the collaboration is very deep. "There's an increased need to share information as clearly as possible across distances," he said. "It helps that I'm fluent in scoring music because I can make a really detailed score and just send it. There's something really powerful about being able to make a piece of music and send it to Australia and then have a group I've never actually met perform it."

Online technologies and tools have become essential to remote collaborative work, for this project and for Dessner's other projects, including a new film score.

Photo: Graham MacIndoe

Film has also become a familiar medium. Dessner previously cowrote the score, with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto, for Alejandro I§†rritu's Academy Award–winning film, The Revenant. After our interview, I learned about another project commissioned by the Manchester International Festival, All of This Unreal Time, a short film and immersive installation for which Bryce and Aaron Dessner and Jon Hopkins composed the score. It should be premiering in Manchester around the time this issue of Stereophile goes to press.

He and his brother Aaron have been riding out the pandemic on different continents, relying on online tools to work together: "We use a fun audio program called Audiomovers, which is a really high-quality kind of monitoring that you can do remotely." Other logistics, such as working across time zones, didn't pose the problems you might expect. "You'd think, 'Oh, it's going to slow everything down working with people in Australia or especially for me in Paris. ... But actually it makes us very effective: Instead of a 12-hour [or] a 10-hour day, we're using all 24 hours, because I can work all day and then send out a score at night, and then I get it back the next morning, already recorded."

A similar approach has been effective for Dessner's popular-music projects, even though that music's technology is different. For example, in pop music, synth samples are often used for strings, or if they are performed, "it's not necessarily done in a way that they're really thinking about capturing the most beautiful sound. Whereas in classical recordings, obviously they make so much effort to find a beautiful space and good conditions for it, and sometimes that difference can be a little difficult to work with." It's necessary to consider both the track's context and practical constraints.

"When you're making something and you want to really try to create the best version of it, you know? At the end of the day, you could probably just use samples on a synthesizer; it'd be fine. Would it be as magical as it could be? No. But it can function musically, still. So that's something that you just have to be humble about and basically understand that you're in support of the larger statement of the song."

Regardless of genre, magic happens, or can happen, when people play together in the same room. COVID has impeded that. Yet, a lot of rock and pop isn't recorded that way anyway: It's assembled from multiple tracks across separate parts, sometimes recorded in different locations. The goal, though, is much the same.

"Whether it's something that's multitracked or done after the fact, we're trying to capture moments in music," Dessner said. "When I record with The National, often you'll hear things that are actually almost improvised, like it might be the first take I did on the song. We keep it, because it has something about it that feels alive, as opposed to feeling really kind of practiced or overly manicured."

- Log in or register to post comments