| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Book Review: Queen of Bebop: The Musical Lives of Sarah Vaughan

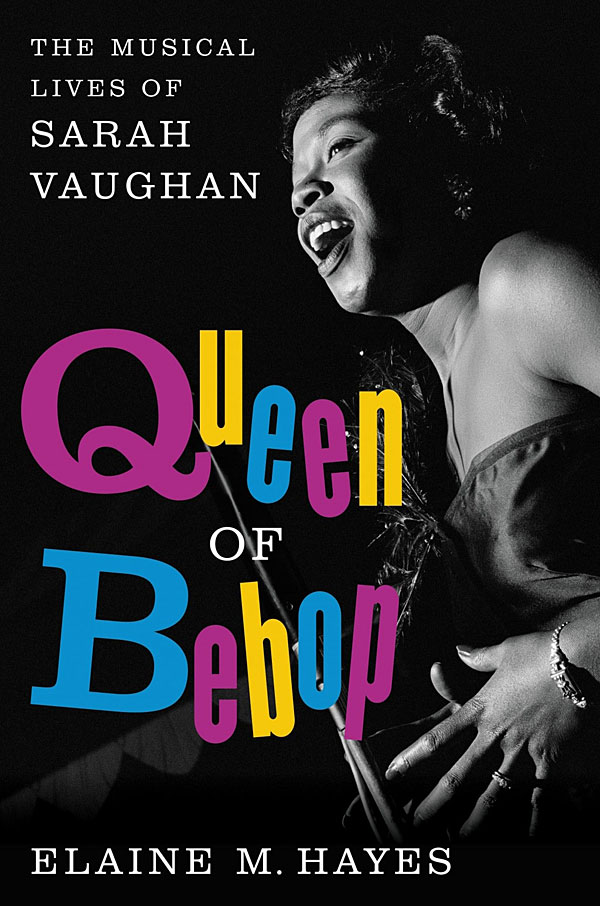

Queen of Bebop: The Musical Lives of Sarah Vaughan

By Elaine M. Hayes. 419 pp. Ecco/HarperCollins, 2017. Hardbound: $27.99. Available in eBook and digital audiobook formats.

By Elaine M. Hayes. 419 pp. Ecco/HarperCollins, 2017. Hardbound: $27.99. Available in eBook and digital audiobook formats.

This is the second biography of Sarah Vaughan (1924–1990), whose towering vocal talents took her to the top rung of the jazz ladder, beside Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. The author, trained as a classical musician, puts far more emphasis on the singer's recordings than Leslie Gourse did in Sassy, her 1993 Vaughan biography. Hayes's grasp of music, and her definitions of the musical terms she uses, make this the better account.

Hayes does, I think, overindulge in sociological speculation. She says, for example, that some of Vaughan's pop records advanced civil rights by projecting a persona not yet associated with black singers. Yes, blacks in the 1950s tended to specialize in blues and calypso, which did convey a simple, sometimes crude image; and yes, Vaughan did try to avoid those styles. Nevertheless, the trivial novelty records she made to fulfill contractual obligations in no way resemble serious musical contributions to the cause.

Vaughan was a staunch admirer of Leontyne Price, the soprano who was one of the first black stars of New York's Metropolitan Opera. She said she would have enjoyed an operatic career, but her family couldn't afford the intensive instruction. So Vaughan plotted an alternate course: After studying piano and singing in her church choir in Newark, New Jersey, she performed in local jazz venues. In 1942, she crossed the Hudson River to enter an amateur-night contest at Harlem's Apollo Theater—a similar Apollo competition had launched Ella Fitzgerald 14 years earlier. As if she were the goddess Athena emerging fully formed from the head of Zeus, Vaughan walked on stage and dazzled the audience.

That led to a gig, with a cutting-edge orchestra, that lasted well over a year. Its leader, pianist Earl "Fatha" Hines, gave Vaughan more than a contract when he hired her to work with an outfit that then included two of bebop's seismic forces, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. Gillespie contended that Vaughan "was as good a musician as anybody" in the group. She said the experience "was just like going to school."

While Vaughan made some of her finest records for Mercury between 1954 and 1959, the company's need for pop hits also resulted in some of her worst. Her all-time bestseller was a silly Mercury single. "God, how I hated it," Vaughan said decades later of "Broken-Hearted Melody," calling it "the corniest thing I ever did," and lamenting that audiences "still ask for it and it drives me nuts." The memorable Vaughan albums Mercury issued on its EmArcy jazz label helped atone for that.

Vaughan had three brief marriages, and she made her men her managers. Emotional problems invariably ensued, and her husbands' lack of business experience and/or scruples caused opportunities and money to vanish. When George Wein, the Newport Jazz Festival's savvy founder, suggested that he manage her career, Vaughan, knowing he was involved with another woman, asked, "How can you?" In Wein's opinion, Vaughan "didn't want a business manager, she wanted somebody to take care of her personally."

Widely known as "the divine one," Vaughan was also called "Sassy," an apt nickname, since she could be rude. Some colleagues called her "Sailor" because she swore. She could also be obstinate. Just before a 1982 concert arranged by Wein's organization, she balked at the all-Gershwin program, griping that she was "fed up with Gershwin," whose work she'd been performing extensively with the classical pianist and conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. Vaughan refused to sing even one Gershwin number. "When she was good, she was very good, and when she was bad, it was miserable," Wein commented.

Don't let this book's title, Queen of Bebop, mislead you. Vaughan wasn't wedded to a single style. Her career lasted nearly five decades, and Hayes diligently details its many hurdles. Naturally, there was racism—in addition to the usual indignities inflicted on blacks, she was beaten during a street attack in Manhattan. There were also mobbed-up club owners reluctant to pay her, unscrupulous record producers, rock'n'roll's bludgeoning impact on jazz, and, beginning in 1967, a five-year recording hiatus. Her Gershwin concerts with Tilson Thomas and various symphony orchestras, and an excursion into Brazilian music, helped right a foundering ship, but the singer's odyssey ended shortly after Vaughan, a heavy smoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer. She gave her final performance in October 1989, and died in April 1990, a week after turning 66.

Though internationally heralded, Sarah Vaughan did have detractors. Whitney Balliett, The New Yorker's jazz critic, said she reduced songs "to technique and four octaves," adding, "I admire her, but she doesn't move me." Audiences and musicians, though, were mad about the girl. "Pure genius," proclaimed Roy Haynes, her drummer in the late 1950s; "a female Charlie Parker." The bassist Richard Davis, who also backed her then, marveled that "she would bend those notes into five different shapes. One note. Five different shapes! And you say, 'God, what's she gonna do next?'"—David Lander

- Log in or register to post comments