| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Can't recommend this book enough—a critical reframing of James Brown written with passion, humor, and power. I wish more music books had the swing of this one.

Comparing James McBride's search for James Brown with the quest depicted in the classic John Ford film The Searchers reveals some dramatic changes in American racial attitudes over the years, along with some consistencies. Ford's film begins in post–Civil War Texas; its white protagonist, a former Confederate soldier named Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), spends most of the film hunting for the Comanches who've kidnapped his niece. To Edwards, such captives are tainted—"they ain't white," he rails—and he intends to kill the girl when he finds her.

McBride, who is black, is out to uncover the true nature of a fellow African-American, James Brown (1933–2006), the Godfather of Soul—one of our "most recognizable entertainers" ever, but a man now "tumbling toward history as an enigma." This quest sheds light on Brown's music as well as his character, it bares facets of the African-American spirit, and it probes the nation in which that spirit has managed to thrive.

Born to a black minister and his white wife, McBride grew up in New York City, studied musical composition at Oberlin, and earned a degree in journalism at Columbia. He's written for major publications, has composed music for Spike Lee films, and, on saxophone, has backed Little Jimmy Scott. McBride won a National Book Award for The Good Lord Bird, a historical novel about the abolitionist John Brown, and his vivid, often tender depictions of supporting characters in the James Brown saga showcase his novelistic skills. The book mingles rapid-fire volleys of short sentences, invariably on target, with extended sentences that never become tangled. It's easy and enjoyable to read.

Born to a black minister and his white wife, McBride grew up in New York City, studied musical composition at Oberlin, and earned a degree in journalism at Columbia. He's written for major publications, has composed music for Spike Lee films, and, on saxophone, has backed Little Jimmy Scott. McBride won a National Book Award for The Good Lord Bird, a historical novel about the abolitionist John Brown, and his vivid, often tender depictions of supporting characters in the James Brown saga showcase his novelistic skills. The book mingles rapid-fire volleys of short sentences, invariably on target, with extended sentences that never become tangled. It's easy and enjoyable to read.

In The Searchers, prejudice helps perpetuate a murderous cycle of revenge; in Kill 'Em and Leave, the bigotry McBride documents tends to involve money. "How many times have I seen this," he wonders as he interviews Nafloyd Scott, then the last surviving member of the Famous Flames, Brown's earliest musical group. "A black musician who never got paid. Take his head off his body and screw on another head and you'll see half my friends." Law firms and their maneuvers have replaced the posses and repeating rifles of Hollywood Westerns. Brown willed most of his estate, estimated at $100 million or more, to needy children, a bequest that sparked a decade of feuding among his family members—as McBride describes it, "forty-seven lawsuits comprising more than four thousand pages of litigation, an estimated ninety lawyers . . . and ten years of court fighting." In 2013 and 2014 alone, an accounting firm charged family members more than $650,000, and one law firm charged $1.6 million. The terrain of The Searchers has yielded to a "new America . . . where the n-word is verboten but the notion of poverty is not; a world with liars on both sides of the racial divide who will say anything and twist history any way they can in order to gain a percentage."

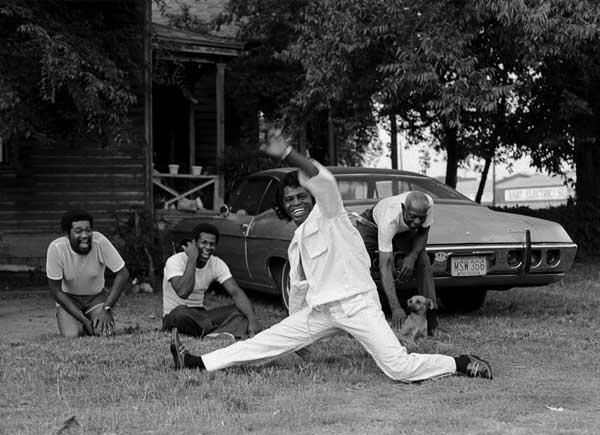

Ethan Edwards spends five years tracking his prey through wilderness; McBride finds his quarry elusive in other ways. "He didn't want you to know him," says Charles Bobbit, Brown's former manager and right-hand man. Bobbit was "as close to James Brown as anyone in this world," yet they addressed each other as Mr. Bobbit and Mr. Brown, a formality that prevailed among many of the singer's friends. Bobbit would also have to "figure out which James Brown [he was] talking to today, because there was about three of him . . . He even had two or three signatures." Brown once faked his ancestry for a biographer, and refused to put himself on exhibit after performing. "Kill 'em and leave," he'd say.

Brown was a clash of contradictions, abusive yet generous to a fault. "During the 1960s, his concerts featured ninety-nine cent tickets for kids ten and under," reports McBride, who notes that the musician dressed as Santa for a 1971 holiday event at Harlem's Apollo Theater. "He handed out free turkeys and Christmas gifts till just days before he died, even giving away his coat and working in the cold, shivering. He provided scholarships, furnished local football teams with uniforms, bought dozens of new computers for community centers, talked high school dropouts back into school." Brown was especially fervent about schooling. "Even during his worst years, in the mid-eighties, when he was broke," McBride relates, he "refused to do sneaker or beer commercials. 'Children need education, [not] sneakers and beer,'" Brown explained. He once made a grandson sweep grass for hours, then warned, "If you don't have an education, that's the kind of job you gonna have."

Churlish to band members, often brutal toward women, in his last years Brown degenerated, emotionally and physically. Nevertheless, McBride abhors the sensationalism that sizzles and spits across so many accounts of the man. He calls Get On Up, the 2014 film about Brown, "a perfect storm of wrong history," fuming that it's "roughly 40 percent fiction" without "one iota of sophistication about black life or . . . black culture."

In Brown's defense, McBride quotes a striking comment from an elderly, churchgoing woman who knew the singer for four decades. "I've never met anyone in my life that worked harder to hide his true heart," says Emma Austin, the longtime wife of Leon Austin, Brown's friend since childhood. "Mr. Brown worked at that very hard. He had a sensitive heart. If you knew that about him, there was not much else you needed to know."—David Lander

Can't recommend this book enough—a critical reframing of James Brown written with passion, humor, and power. I wish more music books had the swing of this one.

When I was a little boy, my cousins (who were friends with Alan Freed) would say that Live At The Apollo was the greatest album ever made. It was only much later, age 20 and older, when I began to appreciate Brown's influence. In 1967 when I was in Germany, they released Say It Loud I'm Black And I'm Proud. I remember the influence of that recording, and others like It's My Country, from close up. Unforgettable.