| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I guess Paul Giamatti will be cast in the movie.

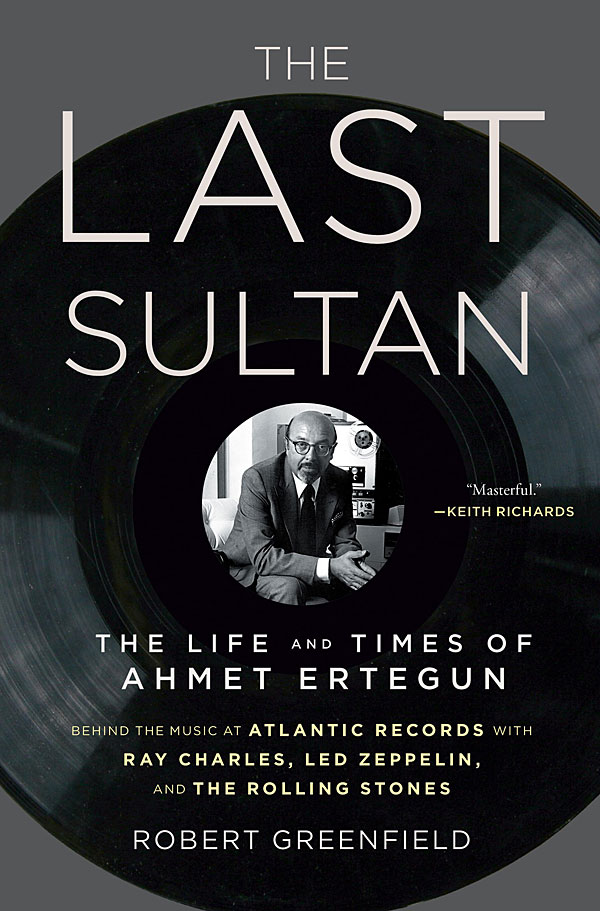

Robert Greenfield's engaging biography shows that Ahmet Ertegun was destined to dominate. The son of a Turkish ambassador, Ertegun (1923–2006) left his native country at age two, and lived for a decade in Switzerland, France, and England, where he had a nanny who had previously cared for the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. His first American home was an architectural gem of a mansion on Washington's Embassy Row. House guests included Cary Grant and his second wife, the Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton.

While Ertegun excelled in private school, the leisure haunts of his teen years signaled his future as head of Atlantic Records. He gravitated toward "Waxie Maxie" Silverman's Quality Radio Repair Shop, which stocked recordings by black artists, and the Howard Theatre, the capital's counterpart to Harlem's Apollo. He had fallen hard for jazz when he heard Duke Ellington at the London Palladium, and while in Washington, he and his older brother, Nesuhi, amassed a collection of 20,000 78rpm discs.

Ertegun, who was generally known by his first name—the singer Otis Redding pronounced it Omelet, apparently thinking he liked the dish enough to have been nicknamed for it—said he first visited a Manhattan night spot when he was 12 or 13. As legend has it, he accompanied a Turkish military officer to the city, ventured alone to Harlem's Plantation Club, managed to get in, chatted with the trumpeter Hot Lips Page, and met a chorus girl who later escorted him to an after-hours rent party, where the stride pianist James P. Johnson introduced him to marijuana. That's one walloping walkabout tale; coming from a known raconteur, it could be an embellished account or an outright fish story, yet Greenfield swallows it whole without a single "so he claimed."

The Ertegun brothers befriended black performers they met backstage at the Howard, invited them home for lunches despite the city's strict segregationist policy, and by 1942 were producing jazz concerts with Sidney Bechet, Lester Young, and others. Nesuhi later oversaw production of Atlantic's jazz recordings, and became one of the genre's most respected figures. Ahmet's musical view also embraced more popular formats, which made his independent label extremely successful.

Ahmet Ertegun's pronounced personal style—he appeared in public impeccably attired in a bespoke suit accented by a pocket square, and relished the sumptuous—projected an image of affluence that preceded the wealth he ultimately accumulated. In the 1950s, when he said he probably had less than $10,000 in the bank, newspaper columnists who spotted him arriving at Manhattan clubs in a chauffeured Rolls-Royce began calling him "the Turkish millionaire." A string of parking tickets had led him to acquire the Rolls used, and hire a distinguished-looking ex-cop to drive him.

Ertegun started Atlantic in 1947 with two dentists. Herb Abramson was a fellow Howard Theatre regular who, as a practical measure, got military-funded dental training; he had cofounded Jubilee Records, and could provide that experience. Vahdi Sabit, the Ertegun family dentist, supplied capital. Ahmet brought to the mix an exceptional flair for music that may have come from his mother, who reportedly could play keyboards and stringed instruments by ear. He also possessed his father's diplomatic aptitude, which proved crucial after Atlantic became part of Warner Bros.–Seven Arts in 1967. To his last days, even in the company of entertainment-industry barons who considered themselves Normans while salting their speech with Anglo-Saxonisms, he remained nimble enough to keep the red carpet underfoot. He socialized with many of his artists, and could cope with "the impossible demands of rock stars." Greenfield says that "Ahmet always found a way to deal with them."

Greenfield's text tilts toward business, and he shovels ample dirt: Atlantic's first hitmaker, Ruth Brown, sics a lawyer on Ertegun to recover royalties she claims she's been owed for decades; David Geffen's "love-at-first-sight" relationship with Ahmet, which began when Geffen was managing Crosby, Stills &Nash, is repeatedly fractured; etc. But the author also imparts absorbing lore about several stars who have lit the Atlantic firmament, from early luminaries like Brown, Ray Charles, and Bobby Darin through Kid Rock, who in the 1990s became Ertegun's "young Elvis."

Some business-side figures are well worth the space devoted to them, notably Jerry Wexler, the savvy former Billboard staffer who replaced Herb Abramson at Atlantic and coined the phrase rhythm and blues; and the Chess men. The Chicago-based brothers, Leonard and Phil Chess, recorded Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, and Chuck Berry, among others. Leonard called Wexler and Ertegun, the latter born into a Muslim family, "the New York Jews," and both attended his son Marshall's bar mitzvah. Nearly 20 years later, Marshall Chess was a key factor in the creation of Rolling Stones Records, and a related distribution deal with Atlantic that made the Stones the jewels in Ertegun's crown.

The book's title comes from a comment made by one of Ertegun's countless lady friends, who was referring to his womanizing when she called him "the last sultan of Turkey." The characterization is apt in other ways as well. Ahmet Ertegun was, after all, a record potentate whose wealth gushed from a well that now is running dry. He habitually reveled till dawn. For him, Greenfield notes, hell was "having to go home early."—David Lander

I guess Paul Giamatti will be cast in the movie.