| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Thanks! for sharing- RB.

"I love 'em because my manager thinks I'm dressed up when I wear them."

"My wife thinks the same thing," I chime in.

"Well, we're in the business of fooling women, right?"

Margolin says he slips four guayaberas into his guitar case when he goes on tour.

"What I really like is the four pockets. I can slip a slide, a capo, and a pick into them. It's really convenient."

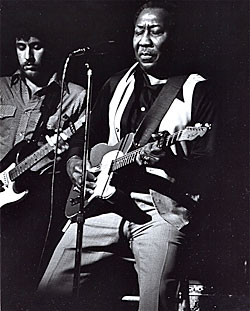

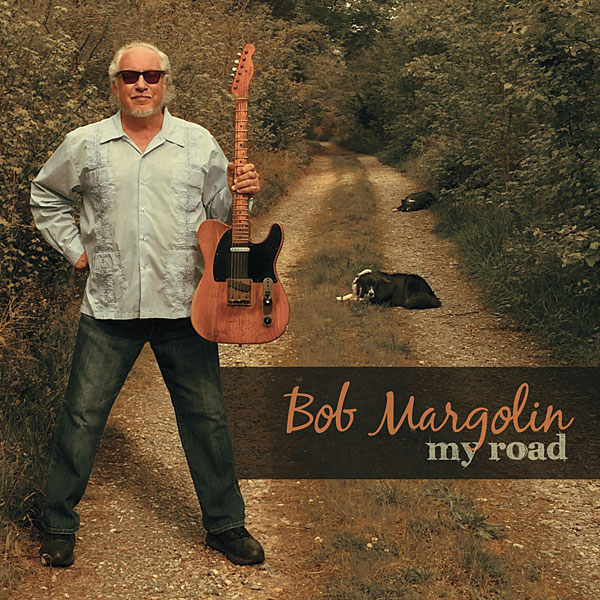

An audiophile and a longtime Stereophile reader, the dapper Margolin, often known by his nickname, "Steady Rollin'" is most famous for playing guitar in the last Muddy Waters Band (1973–1980), and has soldiered on in the blues ever since. If Robert Johnson and the Delta players were the first generation of original blues players, and Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, and the recently deceased B.B. King were the second, then Margolin, at 66, fits squarely into the rapidly diminishing third generation as an elder statesman.

This morning, he's just gotten back to his home in High Point, North Carolina—musically best known as the childhood home of John Coltrane—after a run up north to hook up with Washington, DC-based blues-and-roots band the Nighthawks, for a string of dates in New York and New England. Two days after we spoke, he was leaving for Finland to play a private party. In the blues world, age has certain advantages.

"Right now, I'm walking up and down my long driveway with the dogs after having about a 22-hour day," Margolin says. "The dogs are focused on their ball. They'd give up their lives for me, as long as there's no ball in the room."

The journey to My Road began when Margolin took on a new manager, Pat Morgan, who'd managed two of the guitarist's cohorts in the Waters band: pianist Pinetop Perkins and drummer Willie "Big Eyes" Smith. She had a hand in bringing in Michael Freeman, a well-known producer and engineer of blues recordings who's made albums with Hubert Sumlin, Lonnie Mack, and Bo Diddley, among others, and who produced Joined at the Hip, a 2010 session with Smith and Perkins. Several of Perkins's out-of-print albums, originally recorded for Antones Records, have just been reissued by New West; when Margolin mentions him, we both chuckle in fond remembrance.

"He was younger than I am now when I first knew him. When I joined Muddy Waters's band, he was 60, and I'm 66 now. I thought he was pretty old—and he was—but he was young at heart 'til the end. He had the best death I've ever heard of. About three weeks after the Grammy Awards, he was in his assisted-living place in Austin, and he woke up and played some solitaire, like he liked to do. He always slammed the cards down real hard on the table, like he was a tough guy—which he probably might have been at one point in his life. Anyway, he said, 'I think I'll take a nap.' About an hour later, somebody checked on him, and he was lying on the bed with his hands behind his head and a big smile on his face. At 97, the life had just gently gone out of him."

"He was younger than I am now when I first knew him. When I joined Muddy Waters's band, he was 60, and I'm 66 now. I thought he was pretty old—and he was—but he was young at heart 'til the end. He had the best death I've ever heard of. About three weeks after the Grammy Awards, he was in his assisted-living place in Austin, and he woke up and played some solitaire, like he liked to do. He always slammed the cards down real hard on the table, like he was a tough guy—which he probably might have been at one point in his life. Anyway, he said, 'I think I'll take a nap.' About an hour later, somebody checked on him, and he was lying on the bed with his hands behind his head and a big smile on his face. At 97, the life had just gently gone out of him."

Years ago at South by Southwest, I was standing on the upper floor of an Austin hotel, waiting for an elevator. The bell dinged, the doors swung open, and there was Pinetop Perkins, each of his arms around a much younger woman. He gave me a huge grin.

"His manager would get mad at him for kind of talking shit to the women or touching them inappropriately," Margolin says, then launches into a gruff imitation of Perkins's voice: "'If I was younger, I'd really do somethin' with you, but now every time I try to diddle, it bends in the middle.'"

My Road is to be released on January 8, Elvis Presley's birthday. The album was demoed at Margolin's house using his MacBook Pro, then recorded at Fidelitorium Recordings, a studio in Kernersville, North Carolina, owned by Mitch Easter, who has produced R.E.M. and was a member of Sneakers. The album was recorded on tape, dumped into Pro Tools for mixing, then back out to tape before it was mastered. Margolin says recording engineer Mark Williams uses old Dolby units that give the sound "a certain warm sparkle to it and a very sweet high end." My Road will be available on CD or MP3, but was recorded at 24-bit/48kHz so that it could be mastered for later release on a high-resolution format. Margolin says he might talk to Chad Kassem, of Analogue Productions, about that possibility.

"The studio also has these $10,000 Apogee converters, a really nice, big board, all kinds of good microphones. We worked very hard, but it was in great circumstances. In the '60s, Mose Allison called records 'a very expensive business card.' You don't necessarily make money from it unless you're some kind of big star, which in the blues world, big stars are like a jumbo shrimp—it's still not very big.

"On this record, I really wanted to make no compromises, soundwise or in terms of material. At my age and at this time in my life, and with the music world being as challenging as it is—more so than it's ever been, I think—I really needed to do my best effort and do it now. It was time to make one that would be a break from what I've done before. I've made a bunch of records, some with very original tunes that are not necessarily blues songs, but this time I had to really reach deep inside. I had no idea what I was going to write about. I'm on the bandstand or traveling all the time, so what am I gonna do, write 'This WiFi sucks' or something? Eventually, I wrote six songs myself."

After the six tunes Margolin wrote, another tune on My Road comes from his longtime friend Terry Abrahamson, who wrote what is perhaps the album's bluesiest number, "Heaven Mississippi," which Margolin once demoed and pitched to B.B. King.

"There's two guitars on the demo. One is a little version of B.B. King's single-note playing and some chords, and the other one is open-tuning Mississippi slide—except one note is flat, so it's like a minor-key slide, which is really eerie. It's something that I heard on a Muddy Waters record, and I think he was just out of tune, but it's hard for me to imagine that because he had such good pitch. With a seven-piece band up there, including three guitars and a bass, Muddy could hear if somebody was out of tune, and tell them which string was sharp or flat."

The late Sean Costello, who was diagnosed as bipolar and died from what was ruled an accidental drug overdose, wrote "Low Life Blues," a song about the tortures of drug addiction that Margolin covers on My Road. Tad Walter, who plays harmonica and guitar in Margolin's bass-less trio, wrote "Ask Me No Questions," which Margolin says reminds him of a Hank Williams song.

During the making of My Road, Margolin had an epiphany about his chosen instrument. "I kinda fell in love with one of my guitars. I have a really old Telecaster. It's like one of the first ones—or, at least, most of it is or I couldn't have afforded it. The serial number, before it rusted over, was like 590, something like that. I just love that guitar. In the last couple years, any time I try and pick up another one that I have, even real good ones, nice old ones, that one says 'Me! Me!' Before, they never cared if I spent the night with another one. This one does."

Margolin calls this 1951 relic a "beautiful guitar that stays in tune and never breaks strings." He even went so far as to sell most of his other guitars, and used the windfall to finance the production of My Road.

Like every Margolin record, My Road deliberately echoes the style and approach he learned at the feet of the master. When Margolin joined the Waters band in August 1973, it consisted of drummer Willie Smith, bassist Calvin "Fuzz" Jones, pianist Pinetop Perkins (who had replaced Otis Spann), harmonica player Mojo Buford (who'd replaced Little Walter), and the great Hollywood Fats (Michael Mann) on guitar. Later additions were Luther "Guitar Jr." Johnson and, on harmonica, Jerry Portnoy. Asked what resonates most with him now about his years with Waters, Margolin doesn't hesitate.

"It was a musical foundation. He had his own style, he was literally one of the best in the world at what he did, and I got to learn from him like a master from an apprentice, instead of the way people study music in school, or even just learn it themselves on a bandstand. Getting to stand next to him and get with his timing. Both he and Pinetop used to say something interesting: 'I play for tone.' What does that mean? It could mean that there is a tonal center in what they do, like the key that they're in. It could mean that they like to have a rich, fat tone on their voice or their instruments. I'm not sure. I never asked him, 'What do you really mean by that?' I'm just kind of guessing, but I heard each of them say that separately. I also heard Muddy say, 'You know, my music is so simple, but so few people can play it right.'"

As a musician who cares about recorded sound, Margolin has opinions on the sounds of blues records, old and new. He mentions Muddy Waters's 1964 session, Folk Singer, as an example of a great-sounding record in a genre in which too many sessions were cut quickly, with no budget, in rudimentary studios by engineers with minimal training and worse ears. To generalize just a tad, the object of most blues recordings was not fidelity but feeling.

"I had the opportunity when I was playing with Muddy to ask him, 'How did you guys record? How were those old records made?' And he said that they had a recorder that had three tracks and three microphones. And they would put one in front of the singer, one near the piano, and one near the upright bass. And everything else—the harmonica, electric guitars, and the drums—would all get picked up ambiently, and that would be the mix, that would be the balance. Very often, the singers are loud on those records, but it sounds good. They used good mikes and analog tape, so they sound pretty warm. Muddy's 'Mannish Boy,' the original version, has the most gorgeous kick-drum sound to it. It sounds like a drum in a room instead of a basketball."

In 1976, Waters left Chess Records (which the Chess brothers had sold to GRT in 1969) and signed with guitarist Johnny Winter's Blue Sky label, for which he made three studio albums, all produced by Winter: Hard Again (1977), I'm Ready (1978), and King Bee (1981). Margolin, who played on all three, was tapped to co-produce the 2004 reissues of these records.

"When Hard Again was being made, I asked Johnny Winter, 'How come you don't turn up the bass?' And he said, 'When I heard records as a kid, I couldn't hear the bass anyway, so I really don't want to hear it very loud now.' When we remastered them, I just put a little more bass response in it, and he didn't mind. When we made those records, Johnny had two room mikes near the ceiling, very deliberately. He used them more than most people do. A lot of people will have a couple of condenser mikes, maybe crossed, far away from the band, to get an ambience, and they can put in as much or as little as they want. He put in more than most people, and it really sounded like a band in a room—and it sounded like we were having fun, which we were. It was a great mix."

In the past few years, Margolin has been passing on his accumulated knowledge in workshops conducted under the auspices of the Pinetop Perkins Foundation at the Delta Blues Museum, in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Saying he loves to watch his students' reactions when he recites the words to Muddy Waters's "Hoochie Coochie Man"—which, oddly enough, has the same cadence as a lot of hip-hop numbers—Margolin is clearly committed to trying to create a fourth generation of genuine blues players.

"At first it was just gonna be piano. So I said, 'Why don't we do a guitar class and a harp class?' And now the guitar class is by far the biggest. It's mostly teenagers that come down. We give scholarships to some kids. Some of them are insanely talented and have old souls. They value that music, but they also live in the modern world, and sing and play about what's happening to them. There's no way to explain how good they are, or how deep some of these kids play.

"Of course, there's plenty of kids who just want to plug into pedals and turn up and shred. But there's a really exciting one, a young man that's gonna be a star. He started there when he was 11 and he's 16 now. His name is Christone Ingram, and they call him 'Kingfish.' He lives in Friars Point, Mississippi [the only place Muddy Waters ever saw Robert Johnson, who mentioned the town in several of his songs]. He's starting to get called for festivals, and when the Delta Blues Museum won an award, he went to the White House and played as part of that band.

"The first year Christone was in class, I said, 'Have you ever heard of Freddy King?' He was, like, 11, and he went, 'No.' And I said, 'Here's a picture of him, and you step into your solos the same way he did.' He's a kid, but he just understands the language completely naturally. And now he's started becoming a good singer. We're good friends, and when we play together, time goes away and age goes away. Nothing hurts, and nothing else matters."

Thanks! for sharing- RB.

I've never heard of bob margolin. Great interview; he said a lot of interesting and funny things.