| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Hi Jason- could you expand further on McCarthy's influence on Piston's music? it's not clear to me that there's any connection.

thanks.

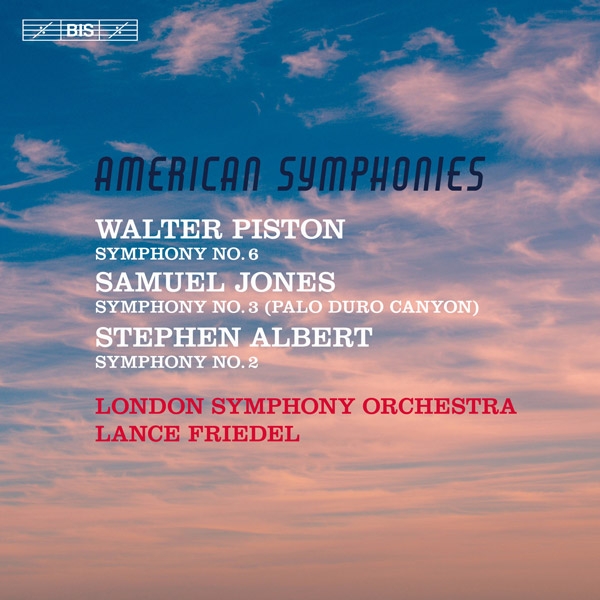

Perception could very well change with the release of Lance Friedel and the London Symphony Orchestra's recent SACD for BIS, American Symphonies (BIS-2118). The recording, which is also available for download and streaming, contains three tonal works: Symphony No.6 by Walter Piston (1894–1976), and the far lesser known Symphony No.3 by Samuel Jones (b. 1935) and Symphony No.2 by Stephen Albert (1941–92).

The biggest find, which I auditioned in the recording's native high resolution of 24/96, is Jones's Symphony No.3 (1992). Commissioned by the Amarillo Symphony Orchestra of Texas, and inspired by the city's nearby Palo Duro Canyon, the single-movement work begins with the sound of steady wind recorded on the Texas plains. In this immediately involving, extremely atmospheric opening, the wind soon declines to reveal an exciting symphonic expanse that has been captured with notable depth in London's Henry Wood Hall by sound engineer Fabian Frank.

At one point, the music sinks into mysterious darkness before opening up once again. Music of tremendous drama builds to an explosion before subsiding. A touchingly plaintive theme on English horn provides a respite before the expansive music returns, even more uplifting and glorious than before. The percussion is mighty, the sounds an involving cross between what sounds like Texas BBQ and, with a little help from Friedel's excellent album notes, Comanche themes. Symphony No.3's glorious canyon theme returns before the LSO strings fade into nothingness, and the work ends with a magical depiction of the night sky that includes the heavenly sounds of celesta and xylophone. Be prepared to hit repeat.

Having mentioned Schwarz, it's important to note that he engaged both Jones and Albert, who were trained at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, to serve as composers-in-residence of the Seattle Symphony. In fact, the only work on this recording that was not previously recorded by Schwarz is Albert's Symphony No.2. Written in 1992 to celebrate the New York Philharmonic's 150th season, it is the final work by a composer who received the Pulitzer Prize in Music in 1981 for his symphony, RiverRun, and a Baltimore Symphony Orchestra commission for a Cello Concerto written for Yo-Yo Ma.

Albert had not finished orchestrating the symphony when he was killed in an auto accident. After the orchestration was completed by Sebastian Currier, Symphony No.2 received its New York premiere in 1994.

The work's 12+ minute opening movement begins rather mysteriously, and then grows. Exactly where it is heading is not clear, at least to these ears. The shorter middle movement, which is as mysterious as it is atmospheric, shares quite a few chuckles as it moves forward at a rapid pace. The near 13-minute finale, which creates an evocative and atmospheric landscape, contains many gorgeous extended passages. The ending is triumphant.

Friedel pegs Piston's Symphony No.6 as the best known of his eight symphonies. Written for Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, who premiered it in 1955 (and recorded it as well), the work is dedicated to the memory of Serge and Natalie Koussevitzky.

As much as I tried, I had trouble finding the "there there" in Piston's opus. Maybe that's because it was written in the mid 1950s, when suburban conformity and McCarthyism were at their height. Then again, Bernstein, who was Piston's student at Harvard, composed Wonderful Town, Serenade, West Side Story, and Candide in the same time period.

Be that as it may, the first movement begins in a lyrical and flowing manner before growing more troubled. The short and very likable second movement, Vivace, includes violins scampering over low percussion. The grave and contemplative 9-minute third movement, marked Adagio sereno, cedes to a four-minute Allegro energico finale. As rousing as its title indicates, its quintessentially American optimism is at one point expressed by three brass groupings—left, right, and center—that seem to dialogue with one another. Copland may have expressed much of the same spirit and energy far better during the previous decade, but that doesn't mean that there aren't many enjoyable passages in the work.

The big rewards of the recording, however, are to be found in the symphonies by Jones and Albert. Don't miss them.

Hi Jason- could you expand further on McCarthy's influence on Piston's music? it's not clear to me that there's any connection.

thanks.

about a time when conformity reigned, and people were fearful of making strong artistic statements that might get them blacklisted. If the connection doesn't ring true for you, so be it.

what type of "strong" musical statement would have gotten Piston in trouble with HUAC?

It gets me to think deeper and examine my statements.

I am hardly suggesting that Piston would have been hauled before HUAC if he had written 12-tone music. In fact, the thought was never in my mind. What I am saying, however, is that I was for most part bored by Symphony No. 6, and that Piston's sticking to the tried/tired and true may have reflected the prevailing social ethos of conformity. Little boxes, little boxes...

After Leonard Bernstein’s April 1960 performance in the White House for President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ike commented, “You know, I liked that last piece you played: it's got a theme. I like music with a theme, not all them arias and barcarolles." Bernstein eventually got his last licks when he titled his final collection of vocal works "Arias and Barcarolles." (My review of San Francisco Symphony's new digital-only release of this cycle will appear in the November print issue.) Other composers never rocked the boat. That's what Piston's music sounds like to me.

I "get" where you're coming from as regards Piston, though, from my perspective, Bernstein is also a "conservative" and reactionary composer in the larger scheme of things.

On the one hand, the records that got pressed, the concerts that got promoted, the "new music" that got publicised in the main-stream press of the '50's did not represent the "outer limits" of the arts in the 1950's. At the same time, some of the most radical "Classical" music was written in that grey and pastel era. Peak years for composers like Xenakis and Stockhausen, with the Fluxus movement emerging towards the end of that era.

I suppose one way of dividing composers is into the categories of good and bad. Simplistic, I know. Consider it triage. Bernstein was not a radical or "far-out" composer, was harmonically conservative but rhythmically interesting, more into Stravinsky than Schoenberg. However, he's a great tunesmith, which is really a different category from "composer". No one is about to say that Benny Andersson is a great composer, I doubt anyone would consider him to be a "composer" at all [they might be wrong]. But he's a genius tunesmith. Similar situation with Bernstein. "West Side Story" gets my vote, "Age of Anxiety" doesn't. Bernstein constantly monkeyed around with flipping high and low art, suppose that makes him Po-Mo. Whatever he was, "Lenny" wasn't boring.

Piston strikes me as one of those composers who attaches himself to a University, like English Ivy. I've heard, and as a recording engineer recorded, a lot of music designed for a grant application. Everything lines up, but the music is basically not interesting. That is still going on.

I'm sure the ratio of good/interesting music to bad/boring music in the 1950's would be about the same as any other decade. Remember, though, that right in the middle of that decade, Rock and Roll first raised its sleazy head, greasy hands and swingin' hips. We're still feeling the shock waves of that musical/sociological revolution.

Great points. Elvis's pelvis tore through it all.

Please note, however, that Bernstein's social commentary was potent and, in its own way, transgressive. Among other things, he had America falling in love with Puerto Ricans... at least on stage. Not exactly what's happening these days.

As for his Mass, which of course came later, people are still coming to terms with it. I saw an absolutely thrilling performance of it once at Oakland Symphony, with dancers celebrating in the aisles.

music is not merely some finely crafted rhythm and note; it also implies a world of personal, social, cultural, political connotation to which one can either intuitively relate or not.

I've been stuck in an enjoyable month-long phase listening to Martinů's works so this was a needed redirect.

I had never heard any of the pieces and I think I give the Piston an edge but I'll listen again.

I wonder if SFS Media has said farewell to physical media? Not an issue for me but curious.

Things are mutable, and MTT leaves in 2020. When he leaves, recording engineer/producer Jack Vad will also take his leave.

I love Piston. Full stop. I react very deeply to most of his music, as "academic" as many find it. Heard the 6th in concert with the Oregon Symphony last year and I fairly leapt out of my seat at the end. It was great.