| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Audio Beginnings

My e-mailbox fills up with press releases announcing new products and new companies, and that always makes me wonder: Where does all this stuff come from?

I mean, I have lots of ideas—I feel like Butch Cassidy: "I have vision, and the rest of the world wears bifocals." But there's a huge gap between having a good idea and starting a company that successfully gets that idea out in front of the public. And, I suspect, there's an even greater gulf between getting a product out there and actually making a living at it.

The great thing about this job, though, is that I don't have to just ponder such questions. The press pass in my fedora's hatband means I can actually call people up and ask 'em about it.

The first generation of audio pioneers is sadly disappearing from the landscape, so I couldn't call Saul Marantz or Avery Fisher, but I could talk to Lew Johnson of Conrad-Johnson, one of the companies that can legitimately be said to have created the current high-end scene, back in the mid-1970s. At that time, the idea that there might be hand-built audio separates that were based on tube circuits seemed almost heretical. I don't know which concept will be more alien to you young 'uns out there—that in 1975 there was no High End or that there was no tube gear. Either way, C-J is one of the companies that changed that.

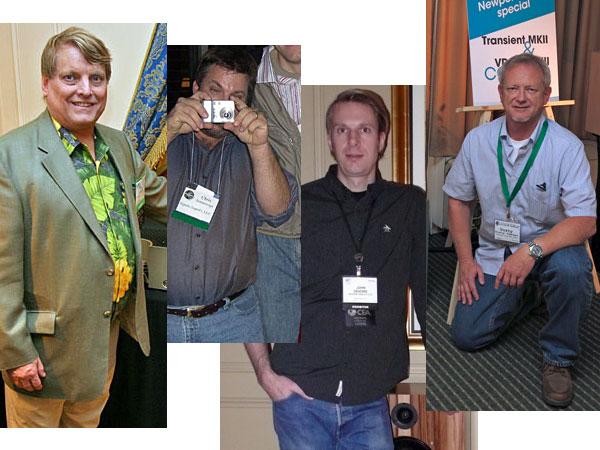

Lew Johnson remembers the beginnings of Conrad-Johnson

In 1975, Bill Conrad and I met when we were both economists at the [Federal Reserve]. Bill was assigned to write a commentary on a research paper I had written, and for about four months or so, that was the basis of our relationship. It wasn't until we both attended a Christmas party that we discovered that we were both into Marantz and Dynaco and the tube gear of the time. We just thought it sounded better.

We were just typical audiophile types doing the "You show me your system and I'll show you mine" thing, and we did a little comparing and arguing over what was better than what—and then we exchanged preamplifiers. We were interested to discover significant differences between Bill's preamp and mine, and we began to speculate about why that was.

It occurred to us that it might be possible to combine the best properties of our two components and have a preamplifier that we were both really happy with. Bill has an extraordinary facility for determining what things are actually going to cost, and we reckoned we could make a product we could actually price competitively.

At first this was an intellectual exercise, but after a week of discussion, we started taking it pretty seriously—and then we spent all of 1976 learning how to build a preamplifier and literally building one from scratch. I made a chassis out of a flat sheet of aluminum and made my own printed-circuit boards, and Bill and I did all the circuit design work. That's how the original Conrad-Johnson Preamplifier was born.

How did you turn C-J into a real business?

With a lot of false starts and a lot of sweat and tears. We spent all of 1976 building the prototype and most of the first half of '77 ordering the bits and pieces and finding someone to assemble it for us, since we didn't have any facilities. We were finally able to incorporate and start selling our first pieces in June of '77. It took roughly six years for us to be able to quit our other jobs.

Do you think you could do it today?

Knowing what I know today, I probably wouldn't attempt it! It's a very different world out there. We were present at the creation of the second golden age of audio, and there's a very different landscape out there today. It would be much harder for a startup company.

Chris Sommovigo recalls how he started Illuminati and Stereovox

Chris Sommovigo was present at the creation, too, only he was present at the creation of the Internet as an audio force to be reckoned with. Ironically, he became involved in the High End because of a claim that he thought made no sense.

Chris Sommovigo: I was a participant on The Audiophile Network bulletin-board server back in the early days of the Internet, and someone on TAN suggested that a digital cable could make a difference. Now that offended me. I had an Audio Alchemy DDD and a Luxman transport and I was pretty happy with them. So this guy sent me some cable that I thought was awful—but that meant it sounded different, and that meant that digital cables did make a difference. So I began talking to John Bauer, a microwave engineer I found through the Yellow Pages, and through him I met a lot of folks doing work in that field. Eventually, John and I came up with the Datastream Reference cable—having basically learned that you needed to match the load to the cable and the connectors.

- Log in or register to post comments