| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Arnie Nudell: From Infinity to Genesis

Arnie Nudell is one of a handful of designers who could justifiably be called founding members of the high-end audio industry. With Cary Christie, and John Ulrick, Arnie co-founded Infinity in his garage in 1968 and recently joined forces with Paul McGowan, the co-founder of PS Audio, to create Genesis Technologies, the Colorado-based company formed to build ultra–high-end loudspeaker systems (see my review of their $22,000 Genesis II.5 loudspeaker system elsewhere in this issue.)

Footnote 1: Robert Harley's talk with Paul McGowan appeared in the February 1985 Stereophile.—Ed.

I visited the Genesis factory in September 1994 and spent some time with Arnie and Paul (footnote 1) discussing loudspeaker and amplifier design, and high-quality music reproduction. I asked Arnie how he became involved in high-end audio.

Arnie Nudell: I was trained as a nuclear physicist and a laser physicist, but when I was very young—eight or nine years old—I started experimenting with various aspects of sound. I made my own loudspeakers, and even some of my own drivers. My mother wouldn't come into my bedroom because I forbade her to touch any of these monstrosities I put together.

I was also a semi-amateur musician. Music was a major part of my life. After being in the aerospace industry for seven years, I realized that, although the aerospace industry was great and physics was great, my first love was music. Along with the love for music was my love for audio equipment—specifically, designing loudspeakers. So it started for me at a very young age.

Robert Harley: Is it true that you started Infinity in your garage?

Nudell: It's definitely a true story. What was actually occurring in my garage was not the formation of a company—at least I didn't think so at the time. I was running the laser lab at Litton Industries and was trying to make every kind of loudspeaker conceivable, including 4/3 Klipschorns.

One of my dreams was to make some kind of a servo system for the bass. There had been some past literature on it, but I had never seen anyone do it successfully. So John Ulrick—who also worked at Litton—and I got together and created a servo system for the bass which we actually thought would work. It was crude in those days compared to what we have now, but nevertheless it was quite satisfactory.

We decided to mate it with electrostatic drivers, which we considered state-of-the-art at the time. We bought some of them, designed the transformers and crossovers, and put it together with a servo bass system. The first test was against the best bass I'd previously heard, which was a 4/3 Klipschorn I had made. It had an 18" woofer in it, and fabulous bass. We put the Klipsch next to our first servo bass system, which looked like a dwarf next to this enormous 4/3 Klipsch.

The minute we compared the systems was when I saw religion. I realized that all the things I had been thinking for so long were absolutely right: that if you could control that woofer in an exact way, and you could measure the motion of that woofer instantaneously at any time, then feed that back to the amplifier, then you really had a terrific bass system. Better, in fact, than any I'd heard before.

The speaker was all done in my garage because that happened to be convenient at the time. When we put this first system together with the electrostatics, we decided we could make them in quantity. We could buy the parts and we knew how to do the servo woofer, so we started a company. This was before Infinity. We did it to get the speaker to some of the local high-end dealers to see what they thought of it and what their customers thought of it. A few dealers actually started selling those things.

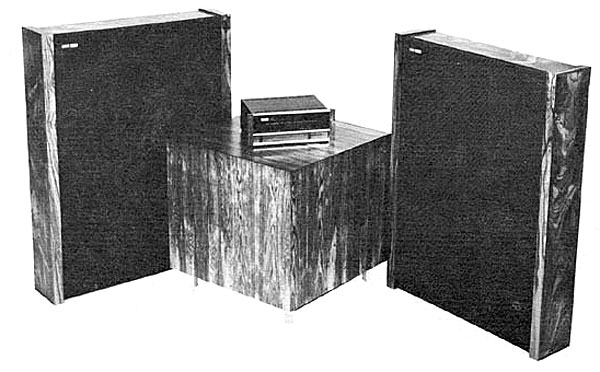

The company was called NuTech Enterprises, but the speaker was called the Servo Statik. We sold so few that we could make them in the garage where they were designed. We were approached by an electronics representative firm—the largest in Southern California at the time—who wanted to manufacture our product. Within a year or so, Infinity was born, and the product was the Servo Statik 1 (footnote 2).

The systems we created were for ourselves, not the basis of starting a company. We wanted them for our living rooms because we didn't like very much what was out there. I had double KLH Nines, matched with Bozak or Klipsch woofers—my own version of Klipsch woofers—but I didn't think the system was very good. That was the motivation to make the Servo Statik, not to start a company.

Harley: How did you and Paul McGowan end up together in 1989 to form Genesis Technologies in Minturn, Colorado, of all places?

Nudell: One of the reasons I left Infinity was that the time I got to spend on design—new materials, drivers, loudspeakers—was so small compared to the rest of my duties. I wasn't doing very much with the thing that really drove me forward, and that was a passion for reproducing music at its finest level.

Harley: You were a loudspeaker designer who wasn't designing loudspeakers.

Nudell: I am a loudspeaker designer, and that's what I do best...

Paul and I were introduced [to each other] by Harry Pearson [founder/editor of The Abso!ute Sound] 18 years ago. For some reason, he thought that Paul and I might have a common interest and might like each other. Sure enough, we met—sat next to each other at one of Harry's parties—and from that day on we became very close friends.

Even when Paul was running PS Audio and I was running Infinity, we got together as often as we possibly could, although we lived about 300 miles apart. In fact, we had marathon weekends where all we would do is go out to dinner and talk about audio and how we were going to do this, and what was wrong with that. That continued for a very long time.

When I'd finally had enough of Infinity, I came out here to Vail because a friend and I had a place in Beaver Creek for skiing in the winter. I decided to come out here in the summer for two, three, or four weeks, relax, and decide what I really wanted to do. It turned out, oddly enough, that Paul was here at the same time, and I didn't know it.

Paul McGowan: My family and I were vacationing in Beaver Creek, and I knew nothing of the fact that Arnie was also there. One day, Harry Pearson called out of the blue—which was unusual, to say the least. Harry said, "Our friend Arnie has just left Infinity. He's just devastated—you've got to help." That didn't sound like Arnie, but I asked where he was. Harry then told me he was in Beaver Creek. It turned out he was right across the street from me. I called Arnie, told him where I was, and we both looked out our windows and waved at each other.

Harry had painted this picture of Arnie being at Infinity all those years and of him being terribly distraught over the whole thing. But when I met Arnie for dinner that night, nothing could have been further from the truth. Arnie was up—he had all these tweeters lined up on the table, and the minute I walked through the door, he started railing at me that he's going to start this new company, and the whole basis of the company is a tweeter. He said that if you have a wonderful tweeter, the rest of it falls into place.

We spent the whole night talking about it. We had a great time. In fact, the tweeter he showed me was the first version of the tweeter we currently use. Arnie was in a great mood, although he looked like he'd been run over by a truck. Running a $70-million-a-year company has its perils.

After that, we talked on the phone on a regular basis. Arnie asked me to work on a business plan for putting a company together. I did that in my spare time, just out of friendship for Arnie. Later, Arnie asked me if I'd like to start a company with him.

Nudell: Understand that, although I designed the first speakers in a condo in Beaver Creek, I had actually turned it into a laboratory. In fact, the living room was hilarious. I wish I had pictures of it. I had a computer, MLSSA, the dbx spectrum analyzer, and a custom switching system. I had state-of-the-art equipment for design.

McGowan: And a rug that was destroyed by soldering irons.

Harley: You started the new company with affordable speakers, working up to the flagship, $70,000 Genesis I. Why did you take this approach?

Nudell: At Infinity we started with a very expensive speaker, the Servo Statik, and brought some of the technology down to lower price levels. We've found that some of the most successful companies, be they audio or anything else, start with the highest technology. After people around the world acknowledge that this is the highest technology, then you bring that technology to more affordable prices.

When we started Genesis, we did it in reverse. It certainly worked okay, but our hearts weren't in it. We knew clearly after a couple of years that it was the incorrect way of doing it.

Our first inclination, of starting at the top, is the correct direction—not just because we're doing it now and we did it at Infinity, but also because it's done by a lot of other successful companies.

The other answer is obvious. Paul's and my interest really lies in the High End, in the state of the art of the reproduction of music. That's where our passions are, and so that's where we're led. While we were making inexpensive loudspeakers, we were getting messages from all over the world encouraging us to make the best loudspeaker we knew how to make. They said, "Hey, you are some of the few guys in the world who could do it. Why don't you go where your interest lies—at the very high end?"

They told us that there's a dearth of product at the high end, and that at those kind of levels there isn't anything new that would set people on fire. After hearing that kind of question over and over, Paul and I looked at each other and said, "Why aren't we doing it? That's where our hearts are, and we're the best in the world at it; we should be doing it."

It's been a joy for us. As you can imagine, it's been difficult designing these kinds of speakers when you're looking for such magnitudes of perfection. I find it gratifying. However, the challenge is: Now that we've created these high-end loudspeakers, people don't expect the lower models to be very different from the model above it. That is a formidable challenge. For example, even though the Genesis V we've introduced is much smaller, people wouldn't expect it to have a soundstage that was truncated in any way. They want a soundstage that's as big as that of the Genesis II or the II.5—which is huge. And if we don't produce that, there's something wrong.

The challenge becomes enormous: how do you do that in a narrow box that stands 40" high with different kinds of drivers? The drivers aren't completely different—it still has a servo bass system and the ribbon tweeter—but many things are different. We're starting to get feedback that we successfully did that. Instead of saying, "Why doesn't it do this or that?," they're saying, "How did you guys do it? It sounds just about as big, and the imaging is as just about as deep, as a II.5."

I don't do it for the customer's expectations, but for my expectations. Hey, the II.5 above it does all this stuff, now I have to make this little guy do almost that—or exactly that if I can. You shoot to make it do everything the II.5 does. But if you fall a little short, and it does, say, 85% to 90% of the model above it, you've succeeded.

Harley: Nearly all your designs throughout your career have been based on three technologies not universally adopted by the rest of the industry: dipolar radiation patterns, servo-driven woofers, and planar drivers. What are the technical and musical advantages of these design approaches?

Nudell: The ideal speaker would be a line-source dipole because of the way it interacts with the room. A line source—if it's narrow enough—has very wide horizontal dispersion, which is exactly what you want, but has no vertical dispersion whatsoever. So it comes out like a sheet of sound at every frequency. And of course there are no floor or ceiling bounces, which are some of the most severe problems in direct-radiating loudspeakers. The first floor-bounce kills the midbass, the ceiling kills some of the ambience in the room. And when you add the first side-wall bounce, all of a sudden you're hearing a muddying combination of the room and the loudspeaker.

Footnote 1: Robert Harley's talk with Paul McGowan appeared in the February 1985 Stereophile.—Ed.

Footnote 2: Reviewed in Stereophile by J. Gordon Holt, Vol.2 No.11, p.19.—Ed.

- Log in or register to post comments