| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Among The Musical #3: Footnoting Rock History with Earl Palmer

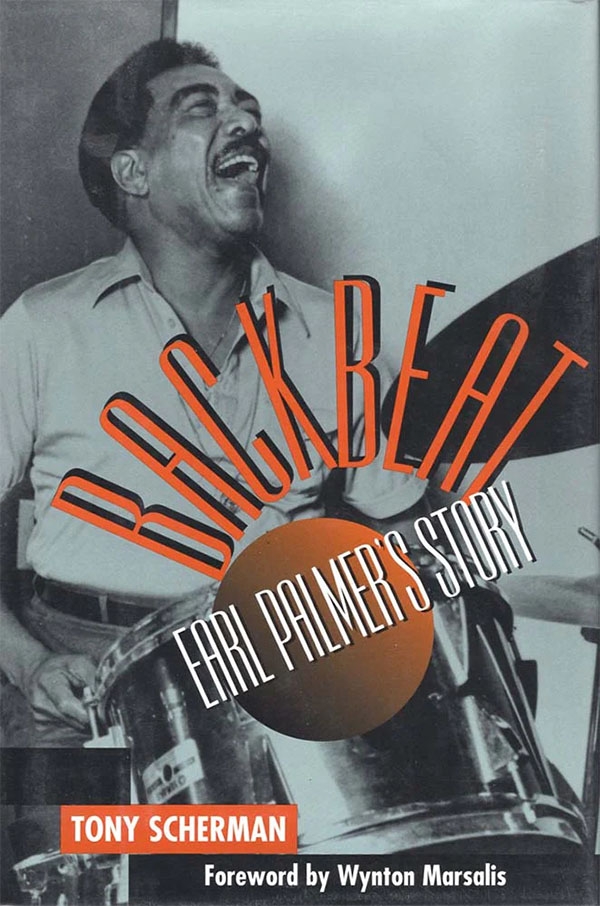

I considered it an exciting discovery. It was an exciting discovery, in the rarefied world of rock'n'roll historiography: namely, that the great New Orleans, later Los Angeles, drummer Earl Palmer was responsible for one of the major paradigm shifts in 20th century American culture: the rock'n'roll beat. The aha moment came when Earl and I were preparing his 1999 oral autobiography, Backbeat: Earl Palmer's Story. Long before my cantankerous interlocutor (Earl ran hot) unspooled his amazing life story for me, a running interview that swallowed the better part of my 1990s, I had come to believe that Earl played a major role, perhaps the major role, in the development of rock's rhythmic underpinnings, hence of the music itself.

Walk with me through a young Earl Palmer's musical surroundings (Earl's dates: 1924–2008). From the late 1940s to the mid-'50s, rhythm & blues was the dominant strain of African-American pop music. In the mid-to-late '50s, R&B was pushed aside by a new sound: rock'n'roll. The characteristic R&B rhythm was the shuffle, whose basic unit is a quarter note divided into a softly played sixteenth note followed by an emphatic dotted eighth note: da-DAHH. Four such quarter notes—da-DAHH da-DAHH da-DAHH da-DAHH—make for one bar of shuffle. Ruth Brown's 1953 smash "Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean" was a shuffle, as was Big Mama Thornton's original '52 take on "Hound Dog." So was Fats Domino's biggest hit, "Blueberry Hill" from 1956, which Earl played on.

Compared to the shuffle's staggered gait, the classic rock'n'roll beat is a propulsive forward thrust: eight eighth notes per measure, a machine-gun–like dat-dat-dat-dat-dat-dat-dat-dat. Think the Beach Boys' "Surfin' U.S.A.," the Surfaris' "Wipe Out," or Del Shannon's "Runaway"—paranoia set to a rock'n'roll beat.

Incidentally, the emphatic two and four—boom-BAP-boom-BAP—that are common to both the shuffle and the rock'n'roll straight-eight have a name: the famous backbeat. Earl Palmer's second innovation (which I overlooked in Backbeat—the book—but which Jonathan Gould points out in his excellent 2017 biography of Otis Redding) was to turn the backbeat from an exciting kick in the pants reserved for a song's final, climactic "shout" chorus into a steady pulse throughout the song.

Back to the straight-eight: Convinced that Earl had played a vital role in its genesis, I grilled him on the many mid-'50s sessions he played on, almost all of them at New Orleans's tiny, minimally equipped J&M Studio, whose coterie of musicians, the so-called Studio Band, comprised rock's first great recording ensemble. (Earl moved to Los Angeles in 1957, where he flourished.)

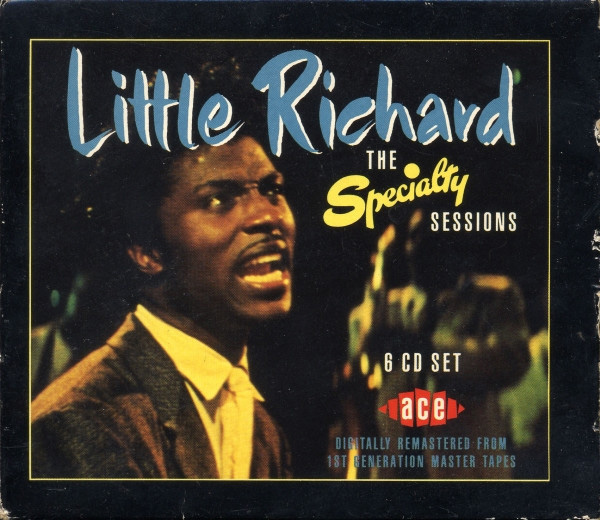

As Earl thought back over those incredibly productive sessions—Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Sam Cooke were all J&M clients—it hit him. Got-damnit, it was during the '55 and '56 sessions, for Specialty Records, in which a virtually unknown Little Richard took a blowtorch to pop music, that Earl shifted gears from the shuffle to the straight-eight. It was a completely unplanned move, a last-ditch effort to keep up with Richard's manic pianistics. Let Earl tell the story:

"Most everything I had done before was a shuffle or slow triplets [the latter a staple of doo-wop tearjerkers like The Platters' "The Great Pretender": bop-bop-bop/bop-bop-bop/bop-bop-bop/bop-bop-bop]. Fats Domino's early things were shuffles. Smiley Lewis's things were shuffles. But Little Richard moved from a shuffle to that straight eighth-note feeling. You got to remember how Richard played—can you imagine matching that? I'll tell you, the only reason I started playing what they come to call a rock'n'roll beat came from trying to match Richard's right hand. Ding-ding-ding-ding!"

A stickler might say that it was Richard, not Earl, who put the key in the ignition, but from where I sat, Palmer was the big V-8 Ford that motorvated R&B into the future.

Of course, I couldn't just take his word for it. Armed with the wonderful 1989 box set Little Richard: The Specialty Sessions, I sat down to some earnest fact-checking. Richard's first J&M session, on September 13 and 14, 1955, yielded only the slow triplets of "I'm Just a Lonely Guy (All Alone)" and shuffles like "Kansas City" and "Tutti Frutti." On the latter, Richard indeed played a straight-eight, but the others, including Earl, were not ready to make the leap. Earl said, "On 'Tutti Frutti' you can hear me playing a shuffle. Listening to it now, it's easy to hear I should have been playing that rock beat."

I pressed on, to Richard's next J&M session, on February 7, 1956, when he cut "Long Tall Sally," "Miss Ann," and "Slippin' and Slidin'." Bingo. On "Slippin' and Slidin'," Earl drove the band from the very first bar with a punishing straight-eight rock'n'roll beat. Hunch confirmed: Earl Palmer invented rock & roll drumming, on February 7, 1956.

Or did he? Had anyone gotten there before Earl? Talk about needle-in-the-haystack searches. Doable or not, I had to give it a go. These were the mid-'90s, when the record industry was spewing out CD reissues, so, hunkering down with as much of the music as I could get my hands on (I love research, love nothing better), I listened, hard, for even one instance of that propulsive straight-eight. Nothing. I checked with the shrinking brotherhood of R&B survivors and primordial rockers, including tenor saxophonist Red Tyler (Earl's best musician friend) and trumpeter/bandleader Dave Bartholomew, Earl's first boss. Neither remembered any earlier straight-eights. Billy Vera, a modern rock guy who went way back, thought it possible that some Latin music had a straight-eight pulse, but agreed that this didn't really apply to my quest. Latin music follows its own logic, different from that of American pop.

I have always hewn to the scientific method: Research a hypothesis until you've either proven it or keeled over in a stupor. On the verge of the latter, I declared the case closed. Backbeat was published, with its privileged glimpse into the birth of rock'n'roll. Earl's account took hold as one of rock's creation myths; in his recent, authoritative biography Chuck Berry: An American Life, for instance, rock historian

RJ Smith acknowledges Earl's role, calling J&M "the birthplace of rock & roll drumming." Earl died happy, a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee confident that he had played a pivotal role in 20th century American music.

The years went by, and a few months ago, as a way of bidding Earl Palmer a final goodbye, I decided to go beyond his Backbeat account and summarize the work I'd done to confirm it. The result was the above paragraphs, which were a pleasure to write. Until they weren't.

I don't know why I hadn't done this earlier, but it occurred to me that in order to airtighten my case, I needed to go back to the Specialty box and listen to the several pre-"Slippin' and Slidin'" sessions that Earl had not played on. One was a demo session at Specialty's office in Los Angeles, held on an unknown date in late 1955. Richard cut nine tracks, some solo, some with an unidentified drummer. All but one, an innocuous shuffle called "Chicken Little Baby," stayed in the vaults. Three, as it happened, were early stabs at "Slippin' and Slidin.'" On the first, playing alone, Richard starts with a shuffle and gradually shifts to a straight-eight. Interesting—a harbinger of what was to come a few months later. On the second, joined by the mystery drummer, Richard plays a straight-eight all the way through while the drummer settles on a sort of Latin groove that verges on a straight-eight but isn't the actual, full-bore bullet train.

On the third, the drummer matches Little Richard step for step with a straight-eight beat from start to finish.

Whoops. It was not Earl Palmer who burst the chains of the shuffle. Mister Big Stuff Researcher done messed up. Someone, some unknown drumnistic hero, had planted the flag on Everest before Earl. Could it have been the man himself, flown out to L.A.? Not for a mere demo session. More conclusively, this was primitive, choppy drumming, not Earl's patented steamroller groove.

Does it really matter? If Earl Palmer hadn't invented the rock'n'roll beat, he certainly established it, celebrated it, on decades' worth of hits, while this other Joe's innovation got filed away. But history is history, and an emendation—a footnote—is in order. Which, if it wasn't what I'd set out to do in this essay, is what it has turned into.

Do I owe it to the muse of rock history to go into full-bore research mode? Adopt heroic measures to identify that unsung pioneer? Not for what I'm getting paid. Besides, it's past time I signed off on the long Earl Palmer chapter of my life.

- Log in or register to post comments