| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

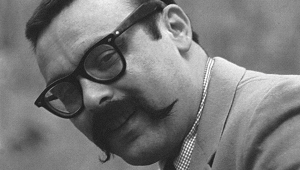

I was in high school when this recording came out; a few months (weeks?) later, Glenn Gould died. That was a musical earthquake in Canada that I still vividly remember. The CBC wouldn’t stop hailing Glenn and his last recording. CTV News would have endless video montages of Glenn Gould performing with famous conductors and orchestras worldwide and how he was the most renowned musician next to Oscar Peterson and Leonard Cohen. It is a good recording, not great; I prefer the Perahia version on CBS, but it is iconic and represents a full circle, as mentioned by Anne Johnson, from his 1955 seminal recording. I will buy it as it captures a moment in time on a quirky, influential pianist whose recordings we should not ignore or forget. Such a great write-up from Anne Johnson, well-detailed regarding the outtakes and recording process—a must-purchase.