| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

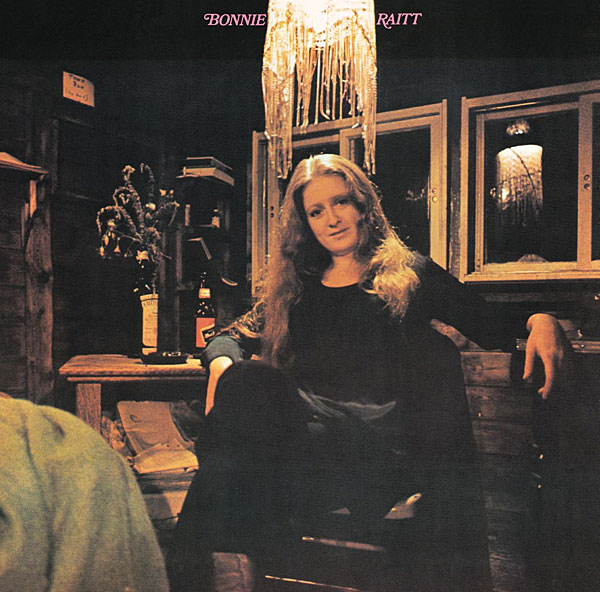

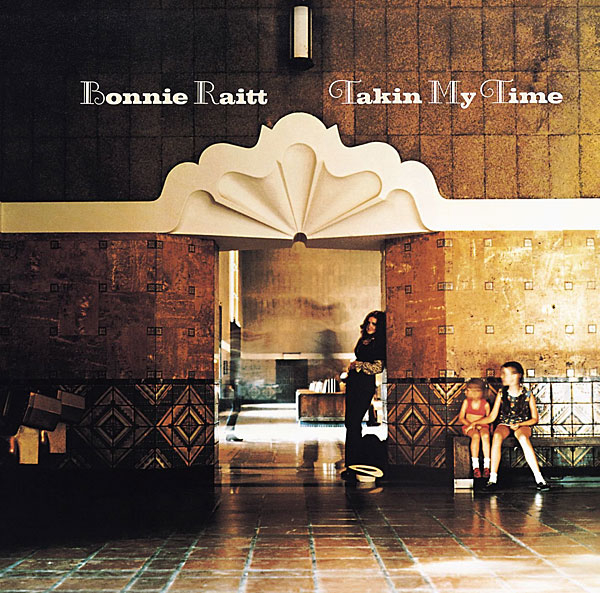

Wow, very telling that Bonnie Raitt is echoing the complaint of so many musicians who were unhappy about the sound quality of the first CD reissues of their earlier albums.

I think this is the reason why so many audiophiles and music fans alike preferred the sound of analog LPs. The first CDs sounded harsh, and like crap.

And now with the loudness wars, engineers weren’t even taking advantage of one of the biggest inherent advantages of digital- dynamic range.

No wonder there’s been so many CD reissues over the years. It’s taken mixing engineers this many takes to start getting it right.

That said, I’m happy with my all digital music collection of CD and SACDs. Finally. For now.

.jpg)