| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Thank you Jason,

This art song piece was beautifully written, inspiring (I am listening to Sandrine Piau now), and well-sorted content-wise BRAVO!

your biggest fan,

herb

As several people approached me afterward to ask about the recording—the album is Chimère—I realized that through a single recorded performance, an entire room had been initiated into the magic of art song. Those present were not put off by a 183-year-old song in a foreign language; rather, because Piau had sung so honestly, so expressively, from such an undeniable place of emotional truth, her performance transcended language and time. That's what can happen when great music and great artistry unite.

I don't recall exactly when my own initiation into art song took place. I had been weaned on opera, which alternated with Elvis and Little Richard from the time I was 11, but art song came later. Browsing my ancient LP collection, I recall, during college, staying up well past midnight comparing interpretations of art songs. By the time I graduated, song recordings featuring accompanist Gerald Moore and artists including Lotte Lehmann, Elisabeth Schumann, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and Hans Hotter had entered my collection.

What was it about this music that spoke to me as strongly as the Beatles, the Stones, Joan Baez, Odetta, and The Band?

I couldn't get enough of the endlessly inventive melodies of Franz Schubert, whose tunes touched my heart and affected my emotional and spiritual being. This New York–born, Long Island–raised boy may have spent six years at summer camp in the woods of Londonderry, Vermont—I'd even managed to catch a fish in Lake Derry—but it wasn't until years later, when I listened in silence to Schubert's "Die Forelle" (The Trout), "Fischerweise" (The Fisherman's Song), and the 16-song cycle, Die schöne Müllerin (The Maid of the Mill; see below for specific recommendations) that I understood the mysteries of a babbling brook and the blessings of a flowing stream. It took the power of Schubert's vocal music to take me out of my private angst and immerse me fully in nature's beauty.

What is art song?

In earlier eras, the term "art song" was used to denote songs composed within the classical tradition, intended primarily for recital and/or concert settings. Some "catholic" definitions restricted the category to songs composed solely for voice and piano. You could get away with a harpsichord or clavichord, but in some circles, you dared not think about guitar and lute (footnote 1).

A major determining factor is intimacy. Most art song was/is written for performance in house concerts or smaller recital halls; it was not envisioned for the opera house. There are exceptions, of course, many of them orchestral songs. Some of the most vital include Hector Berlioz's Les Nuits d'Été, Richard Strauss's Vier letzte lieder (Four Last Songs), Ernest Chausson's open.qobuz.com/album/0825646193868">Poème de l'Amour et de la Mer (Poem of Love and the Sea), the song collections of Gustav Mahler, and Alban Berg's Seven Early Songs and Altenberg Lieder. Some of those song cycles were arranged for both orchestral and piano accompaniment.

Regardless of accompaniment, the power of art song lies in its ability to touch people intimately, as though the performers are speaking to you alone—or to themselves, allowing you to listen in—which is more readily achieved on a smaller scale. The tools of the trade are basic: the quality of voice, breath control, decisions of tempo, dynamics, and shading, and certain other intangibles that allow the artist to connect with an audience.

Today, our understanding of art song has broadened to include a wider range of composition. More than 100 years ago, Johannes Brahms and Antonin Dvorák helped pave the way by incorporating folk melodies into their songs. Thanks in part to two beloved tenors of the early and mid-20th century, John McCormack and Richard Tauber, everything from Irish folk melodies to German popular song has made its way to the recital stage (footnote 2). American mezzo Jan DeGaetani made a convincing case for the songs of Stephen Foster, while tenor Roland Hayes and contralto Marian Anderson ensured a place in the art song repertoire for African-American spirituals.

Art song recitals sometimes also include works from the Great American Songbook (Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, and so on), the best songs intended for the Broadway stage (Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill, Marc Blitzstein, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim), songs intended for the parlor or religious observance (Stephen Foster, Harry T. Burleigh, those traditional African-American spirituals), and folk songs arranged for voice and piano, lute, or guitar. (Britten's arrangements come to mind.) These days, recital attendees are more likely to grin with pleasure than recoil in horror when a recitalist appears without formal dress, accompanies themselves on guitar, throws in some jazz arrangements, or adopts an unusual format and presentation.

What, then, distinguishes an "art song" from songs in rock, pop, country, or jazz? The distinction lies in the composer's intent as much as in presentation and context. Virtually all art song composers, save for those who write "chance" music or jazz pieces meant for concert, expect soloists and accompanists to stick to what's written on the page; few grant artists permission to improvise. That doesn't mean that dynamic, tempo, and emphasis markings aren't sometimes altered for the sake of interpretation—but adapting a song by Schubert to an electronic beat or hyping Stephen Foster's "Beautiful Dreamer" or Schubert's "Ave Maria" with over-romanticized accompaniment can propel these songs into a different category.

Then again, soul songstress Bettye LaVette's deeply moving, high-resolution rendition of Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit," from her album Blackbirds, is a performance worthy of the recital stage. As in Puccini's opera aria "Nessun dorma," which has been sung by everyone from Aretha Franklin to Marie Osmond, what qualifies as art song is a matter of context, quality, and taste (footnote 3).

Distinguishing greatness

To understand how much difference a change of interpretation and voice can make, let's turn to a lovely French mélodie from 1880, Chausson's "Le Colibri" (The Hummingbird), the last of his 7 Mélodies, Op.2.

This is not a grand song. Hummingbirds are hardly vociferous creatures prone to major statements. Besides the subtle whirring of their wings, they seem content to flit silently from blossom to blossom, searching for nectar, although occasionally they alight.

Chausson's setting of Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle's "Le Colibri" describes a green hummingbird that darts into the air as the sun rises. Flying to nearby springs after the scent of red hibiscus beckons, he drinks so much nectar from the plant that he dies without knowing if he's drunk it dry. The song ends with an intimate, human allusion: "On your pure lips, o my beloved/My soul too would have died from the first kiss filled with the perfume of your breath."

If de Lisle's poetry had been set by let's say Richard Strauss or Wagner, one might well expect a grand emotional outpouring, with phrases that grow more intense as they ascend to a soaring climax. But this is French music and Chausson. The climax of "Le Colibri" comes not at the high note but in the many phrases that follow.

I first encountered this song in the 1944 recording by Maggie Teyte. Sounding best on Naxos's two-CD set, Maggie Teyte: A Vocal Portrait, remastered by Ward Marston, it reveals the 57-year-old English soprano, accompanied by Moore, working hard to muster youthful sweetness and radiance of tone. Nonetheless, the translucent high notes and training of an exquisite artist who coached the role of Mélisande with Debussy ensure an idiomatically French performance. Teyte increases dramatic tension while rising to the high note but takes a purposeful breath before hitting it. In doing so, she indicates that the entire song, especially what follows, is of paramount importance. She then sings with increasing intimacy as she slows down at the end, drawing attention to its significance.

Contrast Teyte with soprano Jessye Norman's gorgeously voiced but hardly intimate recording with Michel Dalberto. Norman's interpretation is so fundamentally different that when I first heard it, I wondered if Chausson had written two versions of the song. Presenting "Le Colibri" in much the same manner as she presents Strauss lieder, she builds up to a glorious high note followed by less-than-rapturous phrases that border on the prosaic. Beautiful, yes; "French," no.

"Le Colibri"'s unique perfume has attracted many great artists. The greatest male exponent of French song in the late 1940s through the '70s, baritone Gérard Souzay (footnote 4), made a beautiful honey-voiced mono recording with Jacqueline Bonneau, its ending so unmistakably sensual as to soften the hardest heart. Countertenor Philippe Jaroussky, with Jérôme Ducros, sounds lovely and adorable, the epitome of delicate charm, but he seems more the messenger of someone else's love than the lover himself. The marvelous soprano Sandrine Piau, recording with Susan Manoff in her nectar-voiced prime, channels the springtime sweetness Teyte strove for. The smile in Piau's voice as she slows down and lingers shares secrets beyond words. Recorded just a few years ago, Véronique Gens, again with Manoff, radiates a special, plush warmth. The exquisite manner in which she softly touches notes at the ends of phrases is rewarding, but her ultimate declaration of love sounds as if voiced by someone who chooses not to share her most intimate feelings in public.

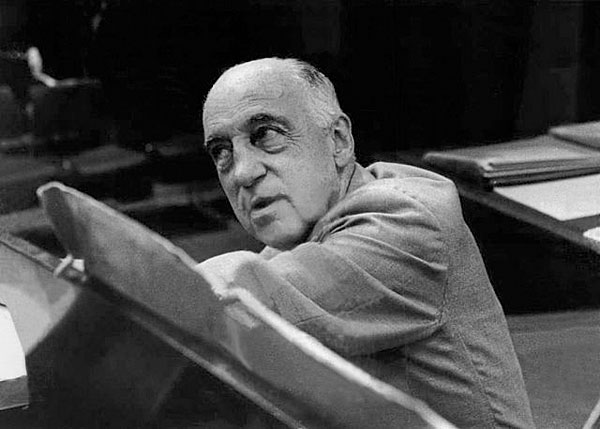

Best of all is the recording by high baritone Pierre Bernac (footnote 5) and his partner in music, Francis Poulenc. Bernac seizes attention with the quality of his voice, the elegance of his phrasing, and the distinctiveness of his pronunciation. An exponent of the open nasal sound of vowels that was the norm during a period when French singers sang their native language almost as if speaking, he sings with unparalleled ecstasy, restraining his passion until the first peak. What follows is incomparable: Singing so delicate, tender, and filled with devotion that you can imagine a man who could walk through dense fields of flowers without damaging a single blossom. This is a magnificent recording by someone who understands that the end of the song is only a small chapter in a greater, life-encompassing story.

Footnote 2: Isobel Bailie and Kathleen Ferrier did the same for English folk song.

Footnote 3: To me, Aretha, who sang "Nessun Dorma" as a stand-in for Luciano Pavarotti at the Grammy Awards, expresses the sense of triumph that's crucial to this song. Not so Marie.

Footnote 4: Encouraged to study voice by baritone Pierre Bernac, who partnered with Francis Poulenc, Souzay studied with Claire Croiza, who worked with Debussy, and Vanni Marcoux, who sang in early performances of Pelléas et Méllisande.

Footnote 5: Bernac, who authored the classic tome, The Interpretation of French Song, counted among his many pupils Souzay, Norman, and Elly Ameling.

Thank you Jason,

This art song piece was beautifully written, inspiring (I am listening to Sandrine Piau now), and well-sorted content-wise BRAVO!

your biggest fan,

herb

This was excellent. Thank you so much.

I can't seem to find an online reference to the disc, but I once had [and re-broadcast on KPFA, when I had a morning slot playing Classical music] an LP containing a documentary produced by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, read by Peter Pears, called something along the lines of "A singer is a Person", pointing out how the instrument of the human voice is also a person, so that much of the color, emotion and range of a singer are tightly bound to that person's history and personality. The instrument spoken of in the documentary happens to be Kathleen Ferrier. Both Britten and Pears worked extensively with Ferrier. I was tickled by Benjamin Britten's offhand remark of Ferrier being "Rather butch". During this time I was regularly reading Alison Bechdel's early work and recording the Woman's Philharmonic for rebroadcast, my immersion in Bay Area social life among classical musicians giving me a whole other angle on this contralto.

The portrait of Ferrier as "one of the boys" pointed to her earthiness, how much "she was a working girl, north of England way", first a telephone operator before entering a vocal contest on a dare, surprised to find herself hitting the bigtime, at least within the realm of Classical vocal recitals and opera. Her ascent was like a pre-echo of the Beatles story. I was completely obsessed with Ferrier's sound, emotion, poise, even though there was no way I could ever know her as a person. I'd be playing the Mahler song "Ich Bin der Welt Abhanden Gekommen" every day for the better part of a year around 1985/1986. Back in the late 1980s/early 1990s I'd be hunting records all over Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco. As CDs flourished, the bins of Ameoba and Rasputin's filled up with old, mostly unplayed treasures. So I managed to own and listen to most of her recordings, including her exquisite collection of folk songs, many performed acapella. "Blow the Wind Southerly" managed to get aired many times when I had an early morning program at KPFA devoted to world music.

But now I'm down to a remastered Decca CD of Mahler's "Das Lied von der Erde" and the three Rückert-Lieder that were in the original 2 LP set on London. While I no longer have a turntable or any LPs, I would recommend tracking down "Das Lied Von Der Erde" (2×LP, Mono) London Records LL 625/626 for those that still do.

What wonderful memories. I was in the Bay Area, early 1980's and wore those record stores out every Friday. It was the OJC jazz reissues back then, for me. They were all of 3 bucks and what a wonder (can't believe those lp's go for as much as they do now). As for Kathleen it was and always will be her Das Linde Von der Erde (sp,I don't have German) with Bruno Walter around 1950 or so. "Erwige... E

rwige..." man, the Farewell was just all that. Gorgeous Decca mono sound if we're gonna do the audio thing and 300B's and horns or Tannoys or both if we must but does it really matter? You cannot harm Ferrier/ Walter. Thank you, kindly, for the exchange.

This article was a fantastic adventure; easily amongst my favorites. Your taste and your insights are really terrific. Thanks.

So glad this feature speaks to you.

jason