| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Damn, we miss you, Art!

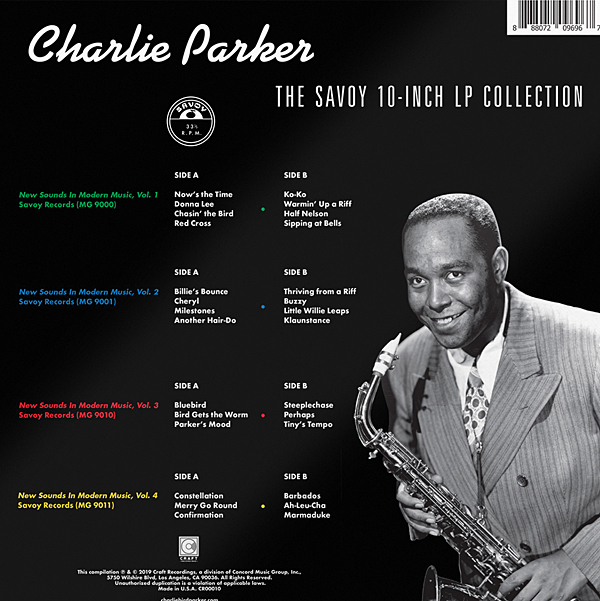

If the original recording sessions were indeed held in 1945, then I would imagine they were recorded direct-to-disc. I believe the first commercially-available magnetic tape recording machine was the Ampex 200, which didn't ship until mid-1948. Perhaps there were earlier prototypes out there used occasionally for testing and de-bugging, but my best guess is that the first-generation medium for these dates is 78rpm disc. (That itself could be a clue as to why the sound is so uniquely present and explosive on Art's LP copy).

Can anyone chime in here regarding the typical re-mastering and cutting workflow used when the primary source material is a 78 or 33 1/3 rpm disc? Are there any good examples or stories of such materials being reissued using a minimalist, all-analog process (meaning one that doesn't impose an intermediate tape generation prior to cutting the lacquer)?

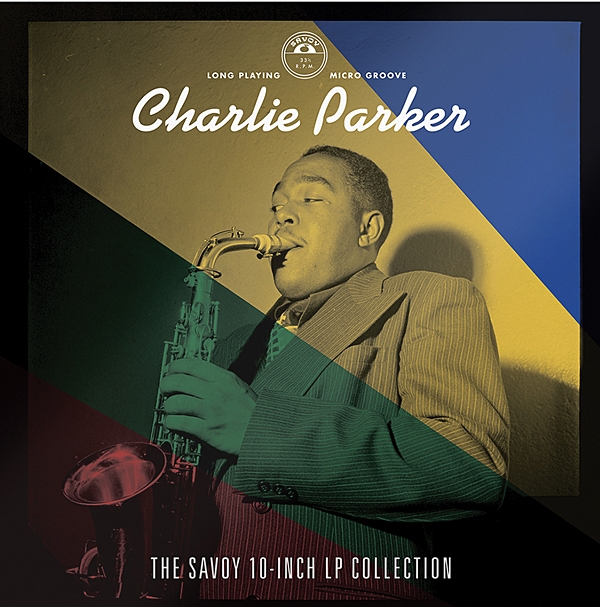

In any case, this reissue set looks like a great introduction to the genius of Charlie Parker and his "backing band" of Miles, Diz, Roach, et al. Thanks for publishing this heads-up within the precious last few words we will ever hear from Mr. Dudley, may you Rest in Peace!