| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I'll investigate this

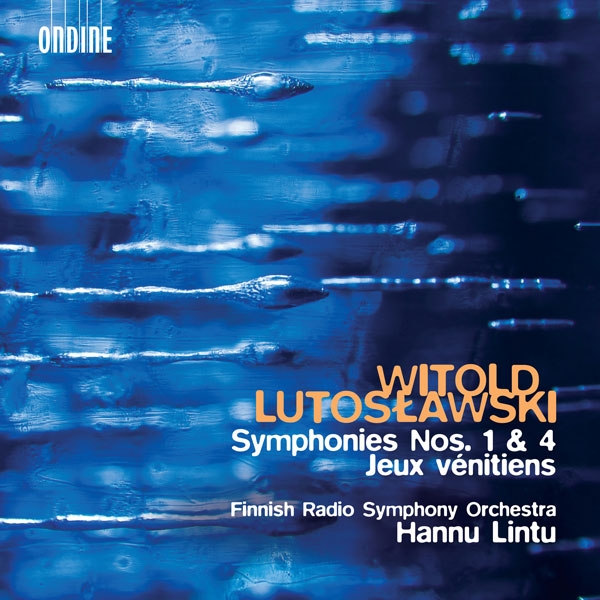

The latter is what I suggest. The more you allow Lutoslawski's strange and wonderful compositions to seize you—the more you allow music-inspired images to surface and float through your mind—the more you will want to listen again and again.

There's really nothing predictable here in the harmonic sense. Symphony No.1 begins with a lot of racing about—a lot of force, aggression and brash energy. Lutoslawski rejected the notion that this symphony reflects what was going on in the world during the six years that the work took form, but it's hard to imagine that a European composer of his sensitivity could have created music on some rarefied level that was completely divorced from the realities of WWII. Whatever the case may be, what is certainly clear is that, as neo-classical as Lutoslawski's writing may be, it paints a very strange world that, at times, is filled with mysterious violence. A degree of dynamic optimism does surface at the start of the First Symphony's final movement, but what to make of that grand, splashy chase and mysterious ending? Just what kind of world is this?

Jeux vénitiens (Venetian Games) was influenced by the chance elements in John Cage's Piano Concerto, which Lutoslawski first encountered on the radio in March 1960. Describing his technique as "controlled aleatorism" (controlled chance, or rolls of the dice), Jeux vénitiens begins with a series of strikes that may at first remind you of a modern take on Verdi's Anvil Chorus. As the strikes continue, however, you will probably sense that they're actually like a series of pistol shots or hammer blows that signal the beginning of the games . . . except that, in this case, each time one of these blows occurs, the nature of the game changes. There's a lot of chaos here—lots of rolls of dice that the composer carefully dispenses to his players—and, once again, a lot of mystery.

Lutoslawski conducted the opening of his Symphony No.4 in Los Angeles in February 1993. A year later, he was dead of cancer. Composed without specific movement divisions, you may find Symphony No.4 positively disorienting. Lutoslawski indisputably knows exactly where he's going, but that doesn't mean that he's going to tell you, or that you can possibly envision the way ahead. At one point, I felt as though I was seeing the bombed out ruins of Warsaw, as depicted in Roman Polanski's film, The Pianist. First I heard a solo violin, whose sound rose above the smoke and ashes. Then there will little cries for help. And then . . .

I've been wanting to review a Lutoslawski recording music for a long time—ever since I became fascinated by his music when I heard Esa Pekka-Salonen, Conductor Designate of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, perform one of Lutoslawski's symphonies with the Los Angeles Philharmonic several decades ago. I waited far too long. As with the music of Anna Thorvaldsdottir and other contemporary Icelandic composers, which creates a sound world and landscape all its own, there's a richness and urgency to Lutoslawski's compositions that must be heard. The more you take the plunge—the more you risk free-fall—the higher you will fly.

Listen up orchestras, this is exciting material. Very intriguing. Drop those safe chestnuts that we've heard all too often and bring us something like these compositions, something we can bite into. Bravo, I'm a fan.

I wish I could have heard this ensemble when I was Helsinki a few years ago. I settled for walking around Sibelius Hall.

Thank you JVS for bringing this forward.

Unrelated but I think Salonen is a good choice for SFS. I've reduced my attendance after one too many patrons demonstrated their mobile device addiction but I'm eager to see and hear what Salonen has in store.

Will Jack Vad be producing recordings after MTT steps down?

At this time, Jack intends to depart when MTT does the same in 2020.

Listen to his Cello concerto...fab. My favorite is the 3rd Symphony that he conducts with the BPO, it was recorded in 1985. His unmistakable composing style can be heard throughout his whole works. Challenging but such great music, if you can find an EMI box set on vinyl (from the late 60's or early 70's), of him conducting his 1st, 2nd, Cello Concerto, Concerto for Orchestra and others with the Polish Radio National Orchestra and Polish Chamber Orchestra, just grab it. Fabulous recordings.