| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

When I read the latest issue, I was very impressed by the comprehensiveness and knowledge in this review. Thanks to Richard and the Stereophile crew for taking the time to print (and publish) this.

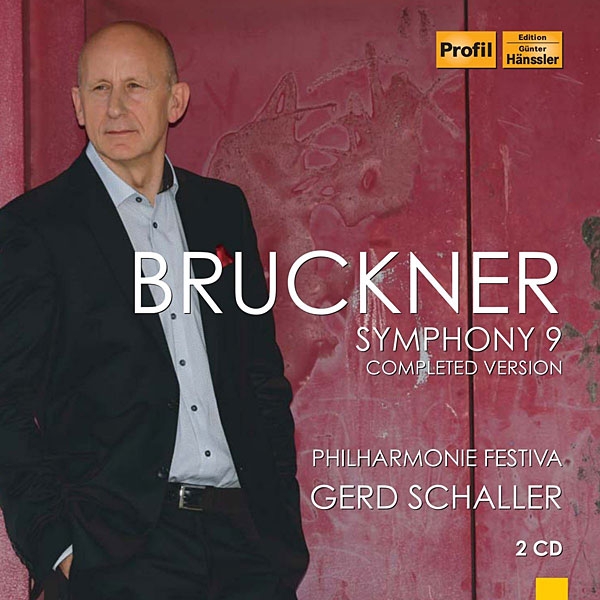

Between 2007 and 2016, Gerd Schaller recorded all 11 of Bruckner's symphonies with the orchestra he founded, the Philharmonie Festiva. In the November 2011 issue I reviewed his 2010 recording of Symphony 9 with William Carragan's completion of the Finale, left incomplete (if perhaps not uncompleted) at Bruckner's death. Six years later, in 2016, with the same orchestra and engineer, and in the same hall—a vast cathedral in Ebrach, Bavaria—Schaller recorded his own completion of the Finale.

Schaller is, I think, one of the two or three finest living interpreters of Bruckner's music. Each of his recordings reveals profound understanding of these vast works' daunting complexity, and an ability to balance the various orchestral voices to bring out aspects of the music that I, at least, had never noticed before, all with a classical poise and restraint, and lack of self-indulgent changes of tempo and dynamics, that in no way lessen the music's power, or the feeling that immensely vital, even dangerous forces of sound, sense, and spirit are being held only just in check: a unique combination of wildness and serenity. That Schaller manages to do this in an immense stone hall with a reverberation time of six seconds—an eternity in sound recording—without it all turning to mush is something of a miracle, and a testament to the discipline of himself, his band, and engineer Lutz Wildner. The sound is wonderful, a seemingly impossible combination of clarity and immense space.

The total timings of the 2010 and 2016 recordings differ by less than a minute; some movements are now shorter, some longer, the differences undetectable except in the Finale, about which more below. In the new recording, the first three movements, left complete at Bruckner's death, are conducted and played, if anything, even more meticulously than in 2010. The muted horn in the first movement—one of the very few times Bruckner asked for this effect—is only just audible far in the distance, creating a powerful sense of mystery and depth. The string ensembles in the metrically challenging two-against-three rhythms Bruckner loved, so difficult and exposed here, are, if anything, further clarified. And Bruckner's long caesuras of scored silence separating and linking the movement's various sections are here given different emphases, some longer, some shorter; each time, the ostensible silence that begins when the orchestra stops playing remains filled with the reverberation of the sounds just made, revealing as in no other way just how big this cathedral is—like lighting a match in what one thought was a small cave and, in the flame's tiny glow, seeing immense walls rising to a ceiling lost in darkness. Breathtaking.

In the Scherzo, the tempo in 2016 is slightly brisker, the orchestra much lighter in heft, with fewer highs in the brass. When I asked Schaller if this was due to a rearrangement of seating, a repositioning of microphones, or a rethinking of orchestral balance, he said, "a performance always is like a photograph of a moment of our life." In this case, the aural photo sounds almost like a rescoring of the Scherzo's da capo section—no violation of the score, but a quite different envisioning of this pounding music. In the 2010 recording, the entrance of the Trio's second subject is taken at the same tempo as the music immediately preceding it; in 2016, Schaller slows considerably, and though Bruckner's score indicates no change in tempo, I think it works better. What remain unchanged are Schaller's amazing delicacy and balance in seeming to make audible everything in the score, and the matching precision of his players. Nonetheless, the 2010 Scherzo has more heft, bite, and power.

The two performances of the Adagio sound most similar to my ear, not least in their excellence. The choir of Wagner tubas in Bruckner's "farewell to life" are gorgeously blended; the recurrences of the anguished first subject sound unbearably poignant and inevitable in the best "I can't go on/I must go on" way. In the latter half, the ostinato of 80 eighth-notes in the woodwinds, slowly increasing in volume to emerge at the top of the sound and suddenly break off at fff followed by a long silence, is here more emphatic. The immense tone cluster not long after this—the Adagio's emotional climax—can be balanced to sound more or less dissonant; I find it far more interesting when no pitch value is cheated but timbres are smoothed as much as possible, as Schaller does here. The result is then dissonance and consonance at once, sweet and sour, pain and joy.

Assembling a completed performing version of the Finale presents unique challenges and problems (footnote 1). In addition to long passages partly or entirely orchestrated in convincingly final form, Bruckner left behind hundreds of pages of sketches, sometimes six drafts deep, all now published in facsimile. Of recorded completions of the Finale I have long preferred the various versions (1983–2012) of the completion by the SPCM team—Nicola Samale, John A. Phillips, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, and Giuseppe Mazzuca—whose operating principle can be summarized as "last thought, best thought." Over three decades, SPCM performed what their theses and papers reveal as exhaustive feats of musicological forensics, to determine which sketch represents Bruckner's last surviving thoughts on any passage missing in final, full-score form. Their completion of the Finale remains the only one that consistently sounds to me as if Bruckner could have written every note. This seems as reasonably attributable to the possibility that they've gotten it more or less right as to what Bruckner's late music feels and sounds like—to me.

Gerd Schaller took a different approach. In some cases he's gone back to Bruckner's earliest sketches to fill gaps in what SPCM call the Finale's "emergent autograph score." (The gaps vary: 2 bars here, 16 or 24 there, per SPCM; the coda is entirely missing.) As Schaller wrote in an e-mail, "you can hear in my completion long distances of unknown Bruckner—for example in the development of the fugue, the recapitulation, in the coda etc. . . . You will hear it immediately—but you have to know all [of the surviving] material." Schaller was not more specific: the score of his completion and his analysis of what he's done have yet to be published, so for each of his interpolations it's unclear which early sketch he chose or what he added to it. The problem with this approach is that it puts all of Bruckner's sketches, from earliest to latest, dated or undated, on equal footing with what other scholars agree are the composer's final thoughts. It's difficult for the non-musicologist who lacks the facsimile edition, and whose score-reading skills are as rudimentary as mine, to know precisely what Schaller has done. One is left with how it sounds and how it feels—words to make any Bruckner scholar wince.

Schaller's completion sounds and feels, by turns, many ways: interesting, jarring, convincing, unconvincing, thrillingly right, not spot on, deeply strange, occasionally like Wagner, briefly like Mahler—all things that have been said of Bruckner's own surviving work in this movement. What Schaller's work does not sound like—to me—is as if Bruckner himself wrote every note. But I find that this bothers me less with each hearing, and less than it bothers me in the Finale completions by William Carragan, Sébastien Letocart, and Nors S. Josephson.

From the first bars, Schaller takes the entire Finale distinctly more slowly than in 2010. This works well: each bar of this complex music registers more fully. Bruckner's dense counterpoint is beautifully articulated throughout, as the main dotted, syncopated leaping motif vaults and plunges relentlessly in three or four directions and voices at once, in the most convincing evocation of infinite possibility that I know of in all of music. Unfortunately, Bruckner's astonishing trumpet dissonances following the first statement of the chorale are so muted as to be inaudible. A variant of the chorale progression sounds jarringly like the "Wanderer" leitmotif from Wagner's Siegfried; Schaller tells me that this is a "development of [Bruckner's] material," but if these four ff chords for brass choir are indeed based on an early Bruckner sketch, I think the composer was right to abandon them. Some of Bruckner's uncompleted pages now sound overcompleted in a work whose first three movements, which Bruckner actually did finish, are starkly austere even for him. Schaller's writing for flutes can be a bit florid to my ear, and occasionally the harmonies and/or voicings seem too richly filled in to sound precisely like late Bruckner. These are matters of taste.

No less so are the many delights. Schaller extends the recapitulation of the great horn theme even longer than do SPCM, to grandly satisfying effect. In the quiet buildup before the coda proper, his realization of Bruckner's sketch of the falling chromatic four-note motif rising as it's handed off among the woodwinds—a sketch that appears in some form in every completion of the Finale—includes the addition (Schaller's?) of syncopated pp punctuations on solo trumpet that echo similar patterns throughout the movement and are the opposite of ornamental. After this comes Schaller's dramatic and nakedly pointed restatement of the first movement's ominous first subject. I don't think that his vertical stacking and development of themes from earlier in this and from other Bruckner symphonies (I hear hints of 4 and 7) is as satisfyingly dense as in the SPCM editions of 1992, 1996, and 2008.

However, one thing I think he gets very right indeed is his coda's length, scope, and scale: It's fully in proportion with the immense symphony it concludes, and in places is awe-inspiring. Throughout, Schaller's coda sounds just enough like Bruckner not to erase my sense and experience of all that precedes it—something I can't say for Carragan's, for all its brilliance. Perhaps my favorite touch is in the bar just before two horns play three ascending notes that abruptly cut off, a staircase that ends in a vast nowhere of silent space: the single swelling oboe note Schaller adds after the one in Bruckner's score—which SPCM delete—here acts as a false leading tone that deliciously misdirects the ear to expect a resolution that then happens quite differently, before the horns defy it. Exquisite.

This recording's first three movements comprise one of the best performances of Bruckner's Ninth ever made. Until Bruckner's lost score pages are found, there will be as many ways to complete the Finale as there are scholars to take it on, and none will be what Bruckner wrote or might have written. Schaller's completion has much to commend it; after SPCM, it is the one I will most want to hear (footnote 2). And it is as beautifully recorded as it is conducted and played.—Richard Lehnert

Footnote 2: When Gerd Schaller sent me a copy of his recording of his completion of Bruckner's Symphony 9 in November 2016, it had just been released in Europe, and was scheduled to be released in the US in March 2017. However, there has been a glitch in the US distribution of these recordings. In the meantime, US readers can obtain the recording here.—Richard Lehnert

When I read the latest issue, I was very impressed by the comprehensiveness and knowledge in this review. Thanks to Richard and the Stereophile crew for taking the time to print (and publish) this.

Well, another Bruckner 9th for me, with part 4 no less. If I live long enough, I might be able to hear these often enough to remember my impressions.

Anyway, here's what I have now:

Rattle, Berlin Phil (with 4th movement).

Gunter Wand, NDR Sym.

Wildner, New Phil Westphalia (with 4th movement).

These are a few other Bruckner 9th recordings that I own and have enjoyed many times:

Bruno Walter, Columbia SO, CBS (recorded in 1959 in the American Legion Hall in Hollywood). This got a Rosette rating when the Penguin Guide was around.

Sir Georg Solti, Chicago SO, London/Decca. You can also get the complete cycle. The CSO is one of the great Bruckner orchestras of them all.

Daniel Barenboim, Berlin PO, Teldec. This is another great cycle. Daniel Barenboim did another cycle in the 1970s with CSO for DG.

Eugen Jochum, Staatskapelle Dresden, EMI or DG (I have that later EMI version). Eugen Jochum and the Staatskapelle Dresden were also among the great purveyors of Bruckner's symphonies.

Gunter Wand, Berlin PO, RCA (yes, there's a partial BPO cycle, too).

Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Vienna PO, RCA. This is a "completed" 9th of sorts. It plays the 4th movement in stages, with stops where there are explanations of each stage of the movement. Allmusic gave this recording a low rating, but Allmusic and Amazon purchasers, and I, like it.

Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minnesota Orchestra, Reference Recordings. This is a good interpretation, and predictably excellent RR recording. I mainly got it to build a a mini-collection of RR, Prof. Johnson recordings. Still it's a good one if you want to augment your collection.

There's an interesting and very favorable review of the recording under discussion in this article by someone in Amazon. Apparently, this person was on hand during the recording of this particular rendering. Here's the information:

https://www.amazon.com/Bruckner-Symphony-9-Completed-Version/dp/B01MAUOE74/ref=pd_sbs_15_img_2/152-3266296-1679936?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=YWJWQC41299GJQ054336

In any event, I look forward to purchasing this recording. Stereophile did an excellent job of reviewing this recording.

A final note: I have never gotten around to purchasing any of the Bruckner orchestras directed by Herbert von Karajan for DG on analog. I have three of the EMI recordings and they are excellent. Perhaps someone can share some insights on the DG Bruckner 9th with Herbert von Karajan.

Some good suggestions here. I'm happy with several recordings I got from the Minnesota site directly. I've enjoyed different recordings by Solti/CSO of the same works, years apart - those make good studies in the evolution of one of my favorite conductors. The records I have with Otmar Suitner and the Staatskapelle are excellent. Suitner does my favorite Beethoven 9th. Barenboim deserves loads of respect for his Beethoven For All cycle with the youth orchestra. I wouldn't be surprised if I bought all of these from Stereophile recommendations.

Unlike other classical music listeners who do not like Karajan, I always found some of his performances fantastic (Schumann, Mahler, R. Strauss) whereas his Bach and most his Mozart (except for his Don Giovanni and Great Mass) left me cold. Yet he is in his element with Bruckner, the 70's recordings are magnificent as are his EMI recordings. His last recordings the 7th and 8th are stellar and it is a pity he died in 1989 before being able to finish the cycle in digital. I own numerous Bruckner cycles and love the Furtwangler and Bohm recordings as well as the Jochum set. All of them are fantastic but there is something to Karajan's approach that works so well with Bruckner. I believe DG reissued the 70's Bruckner cycle so you may be able to get it at a good price. Enjoy!

While we got a good thread going on Bruckner, there are other great works besides the 9th. The ending of Barenboim's BPO Teldec 5th is one of the most hair-raising finales in the recorded repertoire of symphonic music.

Also, we'd be derelict in our duties not mention other great Bruckner interpreters like Riccardo Chailly, Claudio Abbado, Carlo Maria Giulini, Lorin Maazel, Riccardo Muti and Giuseppe Sinopoli.

The Riccardo Chailly Bruckner cycle is one of the finest, though you have to piece it together between two orchestras (RSO Berlin and the Royal Concertgebouw). The starting bars of the 7th Symphony with the RSO Berlin is the most haunting start to the 7th in my collection.

Besides great Bruckner orchestras, there's also the great Jesus Christus Kirche in Berlin, which has served as the recording venue for some of the great "studio recordings" of Bruckner, Karajan's EMI and Chailly's included.

Yes, I agree on the digital DG 7th and 8th done by Herbert von Karajan with the VPO. I believe that the 7th was his very last recording before he passed away.

Go to your liner notes for the digital DG double-deck 8th. There is a line in the text that I will never forget; it's one of the great quotes from any liner notes that I have read for a symphony.

The quote reads exactly as follows (now that I'm home): "Hans Redlich calls it 'Promethean in its aim. Faustian in its spirit, all-embracing in its emotional ambit, spanning the gulf from religious sublimity to the Upper Austrian pastoral idyll.'"

Have avoided Barenboim's Bruckners because I was never that wild about his DG recordings, which I have. Might have to take another plunge, critics do like his latest interpretations. I forgot to mention Abbado, especially his last recording, the 9th, have it on vinyl and CD very good interpretation as was his 4th on DG - good but not great. Sinopoli did some great Bruckner, have his 3rd, 4th, 5th and 7th which are very commendable. Must look at Chailly and before I forget, I must mention the great and until recently overlooked Gunther Wand set own it and love it as well.

So true about that quotation, totally forgot about it, which is what happens when you transfer your CD's to a hard drive and never reach for the liner notes which are filed away in a cabinet.

Bernard Haitink, made some great Buckner recordings.

"....[the Bruckner 8th] is Herculean in its scope, Faustian in its spirit. It bridges the gap between religious sublimity and the Upper Austrian pastoral idyll."

I can certainly vouch for Gunter Wand's 8th, reviewed here I think. Simply beautiful.

For Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra fans, there is some Bruckner to be had. Sony, on its Essential Classics label, has Bruckner 4th and 5th symphonies, probably from the CBS Records epoch.

I have never seen critical reviews of these two renderings, but they are out there for the Ormandy enthusiast. These recordings were made in Town Hall, Philadelphia. The 5th was recorded in 1965, and the 4th in 1967.

that the many attempts at completing the 9th are at least in the spirit of Bruckner.

I have the Wildner completed 9th on Naxos and Rattle's on EMI. I've had difficulty really enjoying either, as parts seem rather foreign.

A little off the beaten path, I enjoyed Dennis Russell Davies' recordings of the 4th (original version) and 8th on Arte Nova. Welser-Most's 5th on EMI is a good reading that makes me sorry he hasn't recorded more Bruckner than he has. I also like Herreweghe's 4th on Harmonia Mundi done with period instruments and smaller orchestra, which gives a different insight into the composition.

I have also enjoyed Titner's Bruckner White Box on Naxos. It seems less well known/regarded, but he takes the tempi slowly and observes the caesuras. It features multiple versions of some symphonies, as well as unedited versions. I think the sometimes glacial pacing, capturing one in moments of space and time, is more in line with the composer's intent, which makes many other recorded versions seem rushed to try to appeal to popular tastes (e.g., those on Telarc in particular).

I saw Muti conduct the CSO in the 4th a few seasons ago. I felt it was a very conventional (popular) reading, and the first movement sunrise sequence was too rushed, especially compared to the brilliantly done sunrise in Mahler's 1st that finished the season, where musical tension was stretched almost to the breaking point and the whole audience seemed (felt) in rapt attention. I very much enjoyed his 2nd in a concert he gave when he first became conductor, and was disappointed only that it was one of the more abbreviated versions of the 2nd! I usually tried to see Haitink's CSO Bruckner performances, as well.