| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Gosh, I'm sure I recall someone in the mid-1970's saying that classical sales were down to 4 percent then. If true, then 2.8 percent wouldn't look so bad.

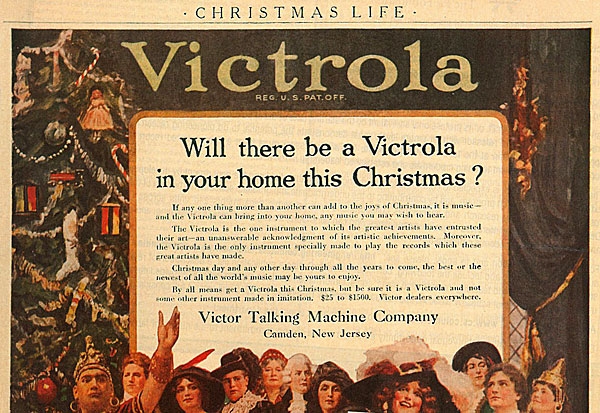

In 1920, "$25 to $1500" was the equivalent of $300 to $18,000 today—which is pretty much the range of what you need to pay to get a halfway-decent audio system or better. But what then caught my eye was the headline of the accompanying article, "When Caruso Was King," and a comment by its writer, Alexander B. Magoun: "As music formats have morphed from vinyl discs to cassettes to CDs and MP3s, the classical recording industry is nearly extinct."

Extinct? Not in 1920. As detailed in Roland Gelatt's superb 1965 book, The Fabulous Phonograph, the meteoric rise of both the record industry and the manufacturers who made the hardware on which to play records was tied to recordings of classical music. Not only was Enrico Caruso the Adele of his time, it was his 260-plus recordings on RCA Victor's Red Seal label that fueled the boom in "talking machines."

Extinct? Not when I was young. My evolution as an audiophile was fueled by recordings of classical music. When I was 11, my parents bought me the Reader's Digest Festival of Light Classical Music, a 12-LP collection of works ranging from Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik to the overture to Wagner's opera Tannhäuser, all recorded by RCA's British A-Team of producer Chuck Gerhardt and engineer Kenneth Wilkinson. And when I started high school, we had a mandatory weekly lesson in "Music Appreciation," in which we were introduced to works like Sibelius's Finlandia, Mars and Jupiter from Holst's The Planets, and the Scherzo of Beethoven's Symphony 3, "Eroica," played on a mono system comprising a Leak "Sandwich" speaker driven by a Leak "Point One" tube amp.

The first classical LP I bought with my own money was of the 1959 modern-instruments performances, by Sir Yehudi Menuhin and the Bath Festival Orchestra, of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos 1–3, followed by Tchaikovsky's Symphony 4 from the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Igor Markevitch. And when I started putting together my own audio system in the mid-1960s, the better the components I bought, the better these LPs sounded. As, of course, did the rock albums I bought—by Cream, Jimi Hendrix, the Byrds, the Beatles—to feed my burgeoning hi-fi habit.

Extinct? Perhaps. As I read the article in IEEE Spectrum, I had just finished preparing our 2016 special issue, 10 Years of Records to Die For: a collection of reviews of 500 albums that Stereophile's hardware and software reviewers could not bear the thought of leaving behind. Stereophile's founder, the late J. Gordon Holt, strongly felt that classical orchestral music was the only music worthy of being played through a true high-fidelity system. Yet just 14 pages of this "Collectors' Edition" are devoted to Classical Orchestral recordings, compared to 20 pages for Jazz. The largest category is Rock (including Pop, Alternative, and Country), at 48 pages—a statistic that I'm sure has JGH reaching for another celestial cigarette.

Extinct? Perhaps yes. According to Nielsen Soundscan, in the US in 2013, classical sales were just 2.8% of the total sales of CDs, cassettes, LPs, and downloads. This is less than half the figure I found for pre-CD 1983, when the amount of money spent in the US on classical records and tapes was 6% of the total, and undoubtedly rose through the rest of that decade as music lovers bought CDs to replace their classical LPs. But by the late 1990s, when Stereophile Inc. sold the Schwann Record Guides to Allegro, a record-distribution company, I was told by the purchaser that it was a rare classical CD that sold more than 1000 copies in its first year of release. And when you consider that schools no longer play classical music to their students and that classical radio stations are disappearing, it's difficult to see where new classical record buyers are going to come from.

Extinct? Perhaps not. Perhaps the statistics don't tell the whole truth. Audiophiles may pay large sums for classical recordings from the 1950s and '60s, when audio engineers didn't yet know enough to know how to ruin the quality of recorded sound—a subject close to JGH's heart. But I believe that we are living in a new Golden Age of classical recording triggered by the advent of high-resolution digital recording and powered by the advent of, first, the SACD medium, and now by high-resolution PCM and DSD downloads—all with sound quality that listeners of Caruso's era could only dream of.

And from their existing catalogs of classical CDs, record companies are offering complete collections at bargain prices. Last year, for example, I bought Decca Sound: The Analogue Years, a boxed set of 50 CDs, for $120—just $2.40 per disc. Similar collections are available from DG Archiv Produktion, DG, Philips, and L'Oiseau-Lyre, with prices per disc dropping to as little as $1.

There's life yet in the music that fueled the fabulous phonograph: If you release it, they will listen.—John Atkinson

Gosh, I'm sure I recall someone in the mid-1970's saying that classical sales were down to 4 percent then. If true, then 2.8 percent wouldn't look so bad.

..is of a far smaller total record sale market than existed in the 70's. So the reduction in actual value is very significant.

..I am amazed at the astounding choice of recordings that are now available to collectors of classical muisc. Far greater and more diverse than existed during earlier periods, up to the 1980s at least.

However this is almost now entirely due to the efforts of the independent record company sector. The majors have a grealy reduced interest in this sector. EMI have gone ( although Warners are reworking the catalogue rather well). CBS/RCA ( the same company in Europe) do release titles but one needs a crystal ball to find out about them. Universal have collapsed three major classical labels into one and now put out far fewer recordings monthly than was the aggregate of the separate labels' output.

As well as the lack of releases from the majors they offer hardly any marketing support to those that they have. For example in this month's Gramophone, the majors have bought only 2.5 pages of advertising ( Universal and Warners) and this is solely related to the passing of Pierre Boulez in one way or another.

Yet I am still dazzled by choice. In fact I believe that this surplus of riches is one thing that puts off newcomers to the music form. It is confusing and they have no idea where to start.

The major labels do very little to market their wares, I suppose the lack of star power - the Karajans, Kleibers, Bohms have not been replaced. Sure there are great conductors and violinists; Nezet-Seguin and James Ehnes but I think the fact that there are no physical retail stores has also hurt their avenues to market and promote as they used to in the past. Plus the demographic and target market isn't like it used to be. During the summer I drove over to Princeton Record Exchange and asked why there was no classical vinyl section (very small) manager said it just doesn't sell. Thankfully their CD section is vast but I was the only one there for the whole afternoon, whereas the rock vinyl section was buzzing with kids. I have been in this classical music hobby for 35 years and aside from Academy Records where there is always a crowd other stores that I visit finds me alone in the classical section. That wasn't the case in the 80's where you could meet people at retail stores and talk and compare recordings. Now that only happens at Academy in my hood.

But you are absolutely right about the smaller independent labels that are releasing some amazing things. I think of the Tallis Scholars with their Gimell record label.

Almost by definition there isn't any NEW classical music, is there?

And so, unlike the 'masses' who buy whatever short-lived so-called 'popular' music currently pushed and advertised as the latest "must have" WE DON'T KEEP BUYING NEW STUFF - there isn't any, other than more 'cover' versions. And of course even the oldest recordings are 'cover' versions anyway as the original performers are long dead. We don't need even more 'cover' versions and so rarely buy them.

How many versions of 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusic' or 'Music for the Royal Fireworks" do I need, for heaven's sake? And unlike vinyl (and even a CD or SACD), a download or CD rip, if backed up against 'accidents', will last forever.

ERGO, sales of classical music are NO indication WHATSOEVER of how much it is listened to. But no one will be still buying Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, or Justin Bieber in 200 years time, that's for sure, but Mozart, Elgar, and the rest will still be listened to (and purchased by those who haven't 'inherited' it). The proof - it's lasted 200 years plus already.

I wonder how many 'Gold Disks' Mozart and Handel have 'sold' in the last 200 years? FAR more than any modern pop musician, at a guess. And it's not really 'classical' at all, that's just a snobbish term - it was the popular music of its day, among that small minority who had any access to music. Now far more people have such access, and again at a guess, I bet far more people are listening to it now than did then, due to both 'accessibility' and the vast population increase.

New operas, symphonies, orchestral pieces, chamber works, etc are premiering all the time. They are being recorded too. Contemporary art music is classical music.

No one EVER sat down thinking "I'm going to write some classical music". Not even Mozart. It had to be 'popular' or they starved, there being no 'welfare' at that time.

That's why I don't like the term (maybe I was not clear on that).

"Contemporary art music" is, again, just terminology. It's not 'classical' as such by any dictionary definition, just new, non-'pop' music. And like MOST of the stuff written 200 plus years ago, only the small truly excellent part of it will survive and then, perhaps be called 'classical' in 2250 or whenever.

I read somewhere that Bach and other composers wandered the streets of their cities occasionally, picking up ideas from local street musicians.

I hope my experience is like a few others at least. I don't go looking for new classical music, or any other genre either, but my small collection of CD's and digital music has grown quite a bit in the last 5 years, from reviews I read here, and suggestions from people on other forums. Having the Internet, and thousands of people pre-screening titles for me (even though it's for everyone, not just me), all I have to do is catch the recommendations here and a few other sites, and I end up with some great recordings. There has never been a better time in my life for finding good music to purchase.

At least half of my listening both live and recorded is contemporary "classical" music but sadly it is a niche of a niche.

One aspect would be interesting to compare the number of visits to live classical music (all ages) to consumption of recorded classical.

I personally think it IS the golden age for classical music in terms of what is being recorded that has never been released before as well as access to the best of the back catalog. From small labels like Hyperion to biggies like Naxos music is being pulled out the archives and made available to us. Some has been forgotten for a reason but there are some real gems there. My 8 month old is lulled to sleep with Max Richters 'sleep' which wasn't released until after he was born!

The orchestras and operas are having a hard time in some places, but if you see the queue for promenading outside the Albert hall in the summer then you can see there is hope.

Seems a little extreme, but there is some truth in my subject. As "education" (most people think of so called "public" education) turns more and more to a technocratic and "efficent" paradigm, things like art and music (and even physical education) are disappearing.

I send my 1st grade daughter to a local Roman Catholic school, not because we are Roman Catholic (we are not) but because they still have a sense of what "education" really is about. For example, it is mandatory that they play an instrument by the 4th grade. I have to drive her to school everyday and while it is probably 70% jazz, I do play classical the rest of the time even though the car is a tough environment for classical. However, in my small city of about 100,000 how many other kids are hearing classical on the way to school? We all know it is at most a handful, probably less...

That's interesting, in that Tradition is what Catholics value so highly in their beliefs, yet tradition is highly suspect in secular education, as the gatekeeper of ignorance, superstition, and prejudices.