| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Silversmith Audio Silver interconnect & speaker cables

The possible approaches to any technical problem range from trial and error to first-principles physics. Then there's the "purist" approach—the simplest, most direct way to meet the challenge. Often, the purist approach doesn't pan out because of such phrases as "we need 60 tons of molten gold" or "can we cool the entire building to absolute zero?" But in the world of high-end cables, the purist approach is viable, and is exactly where you find Jeffrey Smith.

Footnote 1: Hawksford's papers were summarized in "The Essex Echo," in the August 1985 Hi-Fi News & Record Review, and reprinted in revised form in Stereophile, October 1995, Vol.18 No.10.

After digesting Malcolm Omar Hawksford's papers on signal transmission,1 Smith concluded that the answer was obvious: He needed noncorrosive, high-conductivity ribbon conductors in an air dielectric—so that's exactly what he built, first as a hobbyist and then, later, as Silversmith Audio.

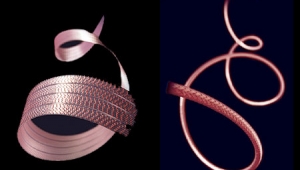

The specifics of the Silversmith Silver cables' design are clever and disarmingly simple, once you know the secret. They're also the subjects of pending patents, so I'll not disclose them here. But the basics are pretty simple: The wide, flat, high-purity silver ribbons are suspended in ultra-thin-walled Teflon tubes in a way that minimizes contact. The interconnects have two (or three for balanced) conductors suspended in individual Teflon tubes, these bundled into a single larger tube and a mesh shield of silver-plated copper. The speaker wires are an even purer expression of the concept, each pair consisting of completely separate units for plus and minus, each composed of a silver ribbon suspended in a mesh-covered Teflon tube. The speaker wires' termination continues the theme by eschewing connectors, instead simply notching the ends of the ribbons to mate with binding posts.

The Silversmith cables are expensive. The interconnect costs $1400 for a 3' unbalanced pair (add $50 for balanced), the speaker cable $2950 for an 8' pair.

The design is pure, but how do they work?

The Silver cables are feather-light and quite flexible, which made them a delight to install and dress. At first I was a little spooked by the apparent delicacy of the speaker cables' terminations, concerned that the ribbon might tear next to the speaker terminals, but they withstood countless manipulations without incident.

The Silvers sounded great, too, handling any sort of music with aplomb and interfacing nicely with a wide range of equipment. They weren't totally transparent, but had a well-balanced mix of subtle characteristics that never interfered with or seemed superimposed on the music. Tonally, they were essentially neutral, resolving low-level details and subtle tonal shadings well enough to clearly identify individual violins and cellos within orchestral sections without sounding overetched. Image edges were well defined and dynamic transients satisfyingly sharp, but again, not at all overemphasized. If anything, the Silvers produced a slightly laid-back presentation with most gear.

Overall, the Silvers reminded me a great deal of the excellent Empirical Audio cables I auditioned in the April issue, though the Silversmiths were a little more of everything—more dynamic, more overt in their resolution of detail, more vivid in their reproduction of tonal colors and textures. But with some material they sounded a touch busy, and couldn't quite match the Empiricals' beguiling purity. As with the Empiricals, I found that the Silversmith interconnects and speaker cables had very similar characteristics and complemented each other beautifully.

I also compared the Silversmiths to two of my reference cables, the Nirvana SX-Ltds and Nordost Valhallas—pretty rarified company, but where the Silversmiths belong. In many ways, they were a nice balance of the Nirvanas' and Nordosts' strengths and weaknesses. Their tonal neutrality, for example, was midway between the Valhallas' slight coolness and the Nirvanas' warmth. And the way they defined images was a nice compromise between the Valhallas' occasional overemphasis of edges and the Nirvanas' slight favoring of coherence over precise boundaries.

The Silvers didn't have the Valhallas' stunning speed and transparency, and slightly reduced the size of dynamic transients. The cello on "Good Vibrations," from Brian Wilson's Smile (CD, Nonesuch 79846-2), was a great example of this comparison. It was rich, woody, and complex with the Silvers, but drop-dead gorgeous and stunningly vivid with the Valhallas. On the other hand, the Valhallas' presentation of Steve Forbert's live set Be Here Now (CD, Rolling Tide) was all contrasts and dynamics, which obscured tonal and spatial information. The Silvers were more balanced and did a better job of keeping everything together.

The Silversmiths also didn't match the Nirvanas' strength: the way they weave everything, including the tiniest details, into a single ambient space that replaces your listening room. One reason, I think, is that the Silvers had a slight background texture that obscured the subtlest ambience cues. Listening to the crowd chatter on "Save Your Love for Me," from Greta Matassa's Live at Tula's (CD, JazzStream JSSACD002), illustrated this clearly. With the Nirvanas, it was an integral part of the sonic picture: distinct, live, correctly proportioned and placed. With the Silvers, the chatter and surrounding noises were mostly obscured; where they were obvious, they sounded superimposed rather than integral.

The flip side was that the Silversmiths were more dynamic than the Nirvanas, especially on large transients and at the f to ffff end of the spectrum. They were also cleaner and more powerful at the frequency extremes. Clipper Anderson's bass on Live at Tula's was articulate and tuneful with both cables, but noticeably more powerful with the Silvers. The upper register of Randy Halberstadt's piano was similarly stronger, faster, and clearer with the Silvers.

Summing up

I was impressed with the Silversmith Silver cables, and found that they compared quite well with my reference wires. Pricewise, they're similar to the Nirvana SX-Ltds—less costly than the Valhallas, but still expensive enough to put them in a market where price isn't likely to be a big driver. Up here, the selection of cables is driven by performance, by which wires best match a given system and listener's priorities. While all three are excellent, the Silversmiths occupy a great middle ground, a nice compromise of strengths and weaknesses that will make them a solid performer no matter the situation.

Based on my time with the Silvers, I'd say that the "purist" approach to high-end cables is a viable one. But if you've already taken the purist route, what's left? What's left is the purist approach executed with no expense spared—the platinum-sledgehammer method. For Jeffrey Smith, it's a palladium sledgehammer—his ultimate cable replaces the silver ribbons with a Pd alloy that, he determined, would optimize the physics of signal transmission.

But that's a much more expensive story for another day. For now, I give Silversmith Audio's Silver cables my enthusiastic and unequivocal recommendation.

Footnote 1: Hawksford's papers were summarized in "The Essex Echo," in the August 1985 Hi-Fi News & Record Review, and reprinted in revised form in Stereophile, October 1995, Vol.18 No.10.

- Log in or register to post comments