| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Recording of May 2006: Tchaikovsky: Symphony 6

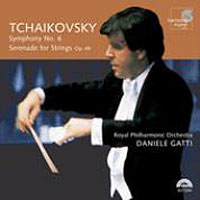

TCHAIKOVSKY: Symphony 6, Serenade for Strings

Daniele Gatti, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Harmonia Mundi HMU 907394 (SACD). 2006. Brad Michel, prod.; Chris Barrett, Craig Silvry, engs. DSD. TT: 77:09

Performance *****

Sonics *****

Daniele Gatti, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Harmonia Mundi HMU 907394 (SACD). 2006. Brad Michel, prod.; Chris Barrett, Craig Silvry, engs. DSD. TT: 77:09

Performance *****

Sonics *****

By now, the most you can hope for from a new recording of one of Tchaikovsky's symphonies is not originality of conception but a performance that seizes on a particular (if familiar) element of the work and successfully runs with it. In his live recording on Naïve, Riccardo Muti makes the anguish in the first movement of Symphony 6 seem an end-of-the-world crisis. Herbert von Karajan's outings with the Berlin Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon give the first-movement rhythms the pulsing regularity of a heartbeat that abruptly stops, with bone-chilling effect.

Though Daniele Gatti's cycle of Tchaikovsky symphonies on Harmonia Mundi has distinguished itself amid the competition, this recording of the "Pathétique" is an experience that stands apart from all other recordings of the work that I've heard. Never has the symphony's logic been clearer. The question many seasoned Tchaikovsky listeners are bound to ask is what logic has to do with a symphony whose commanding expressive content insisted on the creation of an unprecedented symphonic form that includes a waltz in 5/4 meter, and that features Adagios at beginning and end rather than as an inner movement. But Gatti's illumination of the work's shrewd planning and structural integrity has everything to do with giving Tchaikovsky's seemingly impulsive flights a sense of inevitability, and the weight of meaning that accompanies it.

Though Daniele Gatti's cycle of Tchaikovsky symphonies on Harmonia Mundi has distinguished itself amid the competition, this recording of the "Pathétique" is an experience that stands apart from all other recordings of the work that I've heard. Never has the symphony's logic been clearer. The question many seasoned Tchaikovsky listeners are bound to ask is what logic has to do with a symphony whose commanding expressive content insisted on the creation of an unprecedented symphonic form that includes a waltz in 5/4 meter, and that features Adagios at beginning and end rather than as an inner movement. But Gatti's illumination of the work's shrewd planning and structural integrity has everything to do with giving Tchaikovsky's seemingly impulsive flights a sense of inevitability, and the weight of meaning that accompanies it.

The starting point of the interpretation is a rejection of the first-violinist hegemony. You can easily forget how much this is a dominating factor in most symphonic interpretation until you hear this performance's harmonic democracy, how each voice is heard nearly equally, and how that quality—plus the fact that strings don't go into detail-defusing vibrato overdrive—opens the door to other ways of projecting and hearing the music. Gatti resists any perverse spotlighting of obscure details. But how themes, rhythms, and orchestral choirs spring out of and depart from each other (at times, the first movement feels downright fugal) has never been fused so seamlessly with what the music has to say. Although this performance doesn't say anything all that different from the others, it definitely says it differently.

The march-like third movement is one of the most thrilling versions around; there's a great sense of musical simultaneity in the various choirs of the orchestra, and in this performance they bounce off each other with the kind of ensemble telepathy you expect in jazz. When the entire orchestra comes together, you have one of those moments that remind you why something so complex as the symphony orchestra remains an irreplaceable musical medium.

Such descriptions could easily apply to a Pierre Boulez performance, though Gatti's operatic sense of drama, a key element of any successful performance of Tchaikovsky's musical suicide note, is ever present. Exciting surface details are everywhere, the ultimate proof being the final Adagio: Never has the bassoon loitered so plaintively around the string section. Never have the accents in the movement's last minutes felt more like nails pounded into a coffin.

The Serenade for Strings receives a similarly distinguished performance that tastefully balances clarity and surface vitality, each element revealing the other in ways that are appropriate to this lighter, less multidimensional piece. You could ask for more sparkle and sheen, but you can't argue with a performance that shows how the piece's charm lies not in its surfaces but in its DNA.

The Royal Philharmonic has often been at the bottom of the pecking order of London orchestras—I remember some hugely disappointing live concerts under Vladimir Ashkenazy in years past—but here the RPO plays with great personality and accuracy. In some of the climactic outbursts in the final movement, the strings are so imposingly eloquent that I wonder if this is a great orchestra in the making—or one already made. Slightly messy ensemble is heard in some of the first movement's trickier rhythms, but that only tips you off to the HM recording team's priorities, which are clearly about capturing a true performance rather than making a spotless recording. The detail and clarity of the engineering, plus the spacious, airy overall spectrum of the recording (made at the famous Watford Colosseum), cements the conclusion that it is still possible to make a classic Tchaikovsky symphony recording that listeners are likely to enjoy decades in the future, just as recordings made decades ago—Wilhelm Furtwängler's (on Naxos and EMI), or Bernstein's and Mravinsky's second recordings (both on DG)—are today.—David Patrick Stearns

- Log in or register to post comments