| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Bozak Concert Grand B-410 loudspeaker

The Bozak Concert Grand is a loudspeaker dreams are made of. I was just a boy, but I remember to this day the impressive pictures of them in Audio magazine. I thought they must be the best loudspeakers ever made because they were so big—they would let more of the music come out. I suspect the Bozaks beckoned to me in some primal way, just as those giant construction trucks do—the ones that have tires bigger than a man.

Footnote 1: Rudy Bozak designed the first high-quality DJ mixer, the Bozak CMA-10-2DL, back in the mid-1960s, when dance clubs with sound systems were just getting underway. By the late '60s, the CMA-10-2DL had become the standard club mixer, despite being expensive for that era—about $1200. After Bozak's death in 1983, Urei entered the market with a clone of his design, the UREI 1620. In this way, at least, Rudy Bozak can be considered the father of disco and the grandfather of club music and hip-hop.

My dad owned a beautiful pair of Fisher XP-15s speakers, which sat on either side of the fireplace. He would polish their walnut cabinets until the grain popped out, then sit with his eyes closed as the music played. I would hide around the corner in the hallway so as not to disturb Dad. I'd hear marching bands playing Sousa, and orchestras playing Mahler and Beethoven, with a sound so sweet my arms would get goose bumps. But no matter how good the Fishers sounded, I would go to bed and dream of the big Bozaks playing Fantasia in my audio dreamland.

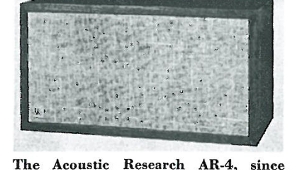

Few could then afford the Concert Grand's 1965 price of $2000 each; fewer still could accommodate their size. Standing 52" tall and as wide as a side-by-side refrigerator-freezer, the CG was an audiophile holy grail in the early 1960s. Each speaker had eight aluminum-diaphragm tweeters, two 5¼" midrange cones, four 12" woofers, and weighed 225 lbs. The Concert Grand was introduced in 1951 and was manufactured through the sale of Bozak to NEAR in 1977.

I heard my first Bozak speakers, a pair of Symphony B-4000As, in a Dallas apartment in the late 1980s. The plain-looking, floorstanding Symphony was the Concert Grand's baby brother, with two fewer woofers and one fewer midrange, and was probably Bozak's best-imaging speaker. About 4' tall, half as wide, and standing side by side against that apartment wall like a pair of curio cabinets, they were wired to a mid-'70s transistor receiver. They sounded boxy and two-dimensional.

As fate would have it, that very same pair of Symphonys would end up at my seashore bungalow 15 years later, where they did vacation-home duty. My goal was simple—set up a utility system that would fit a beach house decorated with a hodgepodge of hand-me-downs. Assuming I'd use the system only for background music, I broke every audiophile rule and rigged the system with cheapo Ace Hardware speaker wire, which, using a kitchen knife, I stuffed out of sight between the carpet and wall molding. And what better source for background music than radio? I had an old Fisher receiver in the attic that looked cool and fit the Bozaks' retro style.

I fired up the system. Bang! I was taken back to my dad's 1965 system. The sound was huge and so realistic, but most of all, it was smooth—the opposite of my high-resolution system. Altogether it had cost less than $1500, and made better sound than most of the high-end systems I've heard. I instantly knew that I'd found what I'd searched for since boyhood. (The Symphony B-4000A is more plentiful on www.Audiogon.com and www.ebay.com than the Concert Grand. You might also try stacking two pairs of B-302As, as one member of the bozak_speakers group does on yahoogroups.)

Still, the Concert Grands presented some problems that gave me pause even as I suggested to John Atkinson that I write a review of them. First, they're very rare and are seldom seen on the second-hand market. Second, they're huge—practically impossible to ship from Philadelphia to New York City so that JA could measure them.

Rudy Bozak and his designs

Rudy T. Bozak (1910–1983) was a hi-fi pioneer and a bit of a maverick, as famous for his loudspeakers as for his pro audio mixers (footnote 1). Bozak raised many eyebrows by refusing to submit review samples to audio magazines for lab testing. Nor did he like to discuss the sonic aspects of his speakers with reviewers and industry experts. It's been reported that he was annoyingly adamant in his belief in the importance of driver-cone material. He thought the "sound" of the cone itself so important that he cooked up in a large cauldron his own raw cone material, using a secret formula of 50% wool and myriad off-the-shelf and more exotic materials. Bozak's woofer cones varied in density from the core to the surround, to achieve a fast but relaxed voice. He changed the composition of the Concert Grand's woofer magnet from alnico to ceramic in mid-year 1970. Bozak fans remain divided as to which sounds best. I have a pair of ceramic-era Symphonys that offer startlingly crisp bass, but have not heard a pair of ceramic-era Concert Grands.

Although the Concert Grand is Rudy Bozak's grand achievement, the Bozak sound is also available in his smaller designs. The Concerto B-302A offers the CG's midrange in a much smaller package (28" H by 24" W by 20" D). The Symphony B-4000A is closer in performance to the CG but in a size that's slightly easier to handle (44" H by 26" W by 15" D).

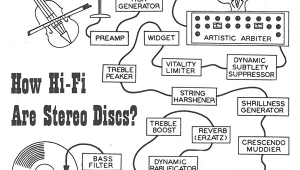

Description

The heart of every Bozak speaker is the 5¼" midrange driver, whose magnet structure is the same size and diameter as that of the 12" woofer. Bozak stated that, "based on the laws of physics, [this unit] is so sized that the diameter of the speaker cone does not exceed the wavelengths of the sounds they are designed to reproduce." The cone itself is made of uniform-density aluminum coated with a thin film of latex rubber on each surface. The aluminum is perforated to help bond the rubber coatings and damp the cone. Legend has it that Rudy Bozak worked on the voicing of this drive-unit to minimize the annoyance of LP tracing distortions.

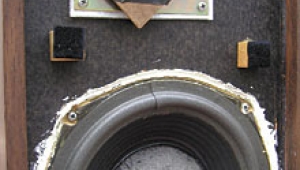

The tweeter is a standard, dual-cone design. The inner aluminum diaphragm handles frequencies above 10kHz, the outer diaphragm the frequencies below 10kHz. Both are coated with rubber and damped with an abutment of foam rubber. Early Concert Grands had a multitweeter array in the shape of an Altec sectional horn; later designs had a line array.

There are a couple of different driver configurations for the Concert Grand. One pair I own places the midrange drivers almost 20" apart on the horizontal plane. I experimented with physically covering one of these to reduce combing artifacts—this made a big improvement in the imaging and increased the seamlessness of the integration with the woofers.

The CG's large (52" H by 36" W by 19" D), massive, particleboard enclosure is designed to be as close to an infinite baffle (a large wall) as possible. In fact, Bozak sold many Concert Grands in kit form where the buyer supplied the enclosure—a wall of the house. (Imagine the wife catching you drilling 14 good-size holes in the living-room wall.) From the mid-'60s through the early '70s, CGs were available in three distinctive cabinet styles—Classic, Contemporary, and Moorish—and were built to a standard of fine furniture at the Bozak factory in Darien, Connecticut. The old-world craftsmanship is a far cry from the robotic look of more modern designs.

The CG's front face, or baffle, is 1.5" thick. The drive-units are mounted to the inside of the baffle with standard wood screws and hooked up with ordinary stranded copper wire. The midrange units are isolated from the woofers and tweeters in a semispherical inner enclosure of plastic, to reduce interference from the backwave. To access the drive-units, you remove the rear of the cabinet by unscrewing 40 large wood screws—no easy task. The enclosures have minimal cross bracing, which gives the cabinets some life when you rap your knuckles on the top and sides—it's as if they're living, breathing things.

Setup

If you live in a walkup apartment, forget about the Concert Grands. If you have a small room, forget about them. If you have neighbors, forget about the CGs. These imposing speakers dominate a room, and should be placed far apart—they need room to breathe. Their bass response is amazing enough that you can also forget about placing them in a room adjacent to a room anyone else is going to use.

It's funny, but the CG looks so "old world" that it's hard to imagine it producing a "modern" sound. Now for the surprise—it's friendly to single-ended-triode (SET) tube amplifiers. I get rock-concert levels with 845s (300Bs for chamber music or jazz), and have found the CGs wonderfully match with 18W, 6BQ5 SET amps to produce a clean, articulate sound. I've had excellent results from a number of such amps, including the EICO HF-81, Stromberg Carlson ASR 433, and Heathkit AA-151. Each served up tight bass and airy highs with three-dimensional images and springwater-like clarity. You'll get more punch as you move up the power curve to 845 and EL34 SET amps, but not better sound.

Footnote 1: Rudy Bozak designed the first high-quality DJ mixer, the Bozak CMA-10-2DL, back in the mid-1960s, when dance clubs with sound systems were just getting underway. By the late '60s, the CMA-10-2DL had become the standard club mixer, despite being expensive for that era—about $1200. After Bozak's death in 1983, Urei entered the market with a clone of his design, the UREI 1620. In this way, at least, Rudy Bozak can be considered the father of disco and the grandfather of club music and hip-hop.

- Log in or register to post comments