| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

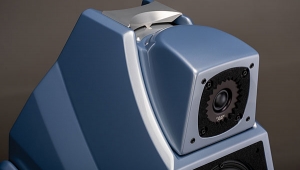

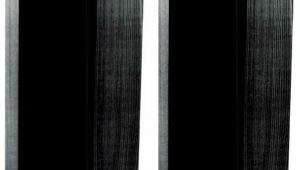

Ruark Templar loudspeaker Page 2

Those used to the bass signature of most ported two-way designs are in for a shock when they hear the Templars. The solidity of the bass image is impressive: punchy, articulate, and phenomenally well-defined. (It did not come as a surprise to learn that Alan O'Rourke plays bass.) Glen Velez's various frame drums were filled with dynamic energy and portrayed with such precision that I could hear his fingers buzz against the membrane as they lightly brushed the slowly moving drumhead. Everything was placed within a well-defined soundstage, which in turn was obviously a different acoustic from the one in which the speakers were located. However, the listener does not inhabit that soundstage, but rather observes it as a reduced-size model as from above. This effect reminded me of sitting in the upper tier of a nightclub, such as the Cellar Door in DC, and looking down on the performers from nearby—as opposed to the upper levels of, say, Carnegie Hall, where distance further reduces the apparent size (and immediacy!) of the musicians.

Footnote 2: If you think you can't make music with two or at least three tones, try singing "Three Blind Mice"—doggerel though it may be, it still proves the point.

Hmmm. Looking down on the performers, eh? Wondering what effect the low tweeter placement had on the imaging, I sat on the floor a few inches in front of my accustomed listening position. This put my ears 31" from the floor and opened up the soundstage to a remarkable extent. Wow. Meaty, beaty, big, and bouncy! Slumping backward even further, to the point where my ears were 25" off the floor (or just below the tweeters' 25.5" placement) put me virtually inside a huge, immediate re-creation of the recorded event. This position, which most resembles that of an abdominal crunch, is one from which I would, undoubtedly, derive inestimable benefit, but is not one that I could support for extended critical listening. So I went back to a normal seated position—where I found the sound more than satisfactory, if not as impressive as that nearer the floor.

Did I say satisfactory? I mean delightful. A lot of speakers (heck, a lot of systems) dictate what music you will enjoy. Dynamic compression, emphasis in a particular band, lack of articulation—all of these limitations, not to mention many others, can force you to ignore vast categories of music; after all, what you don't find entertaining, you won't listen to. The Templars let me explore the full range of my collection. Small-group jazz had a snap and rhythmic flexibility that left me hungry for more. I played MoFi's superb reissue of Cannonball Adderley's Somethin' Else (UDCD-563 CD)—or Kind of Blue, Pt.2, as Michael Fremer has called it—and immediately had to hear one of the CDs from Miles Davis's The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965 (Columbia CK 66955), which meant that I had to listen to all eight discs—which in turn led to a Coltrane marathon, and so on, and so on.

Putting laser to pit on Vanguard's superb reissue (SVC-3) of Earl Wild's performance of the Copland and Menotti Piano Concertos revealed a mondo hugo soundstage with a piano as solid as a boulder sitting in the middle of my room. Exhilarating! What could follow that? Hey, Analogue Productions has just released a remastered LP version (APC 029 LP)! More bigger, more better, more va-va-va-therer! Whew, what else do I have by Earl Wild? The Art of Transcription (Audiofon 2008 LP)—ah-ha! And thus I burned up another night.

It really didn't matter where the explorations started. One thing led to another; one disc reminded of one, five, or ten more; I would pursue the chain of musical thought for hours on end. This is, of course, is what good audio gear should do—inflame musical passions rather than quench them with its shortcomings. But why do the Templars do it to the extent that they do?

Change creates time

I have a theory. But before we look at why musical reproduction—despite its limitations—can be satisfying, we need to look toward what music is first.

According to the musical catechism, the response to the question What is music? is: Music is the progression of tones in time. Interesting response, because we tend to think of music as sound, and this clearly defines music as motion. How can that be? Well, try to make an argument for music as sound—take your favorite tone and listen to it. What have you got? A tone, that's all; it ain't music. Okay, so it takes more than one tone to make music. Take two tones, then. Unless they're separated by time, all you've got is a chord—it still ain't music. But play those tones in sequence and you have music (footnote 2). So the difference between music and not-music is time, and music traveling through time is in motion.

For the purpose of a speaker review, it would be absurd to further parse this thought and try to separate rhythmic motion from the concept that Zuckerkandl calls "the paradox of tonal motion": the notion that, quite apart from rhythm, there's a motion inherent in the progression of tones. But I suppose that I should point out that this whole question gets pretty complex.

This most basic of all tasks—portraying music through its tonal ebb and flow as well as through its metrical organization—is exactly where the Ruarks excel. Other speakers may have wider frequency response (many do). Other speakers may have superior imaging and soundstaging. (It's not that rare.) But the Ruark places tone after tone and throws beat against beat in a way that conjures the music mighty powerfully—disc after disc, hour after hour. That's a very tangible benefit; after all, who cares how good a speaker is technically if you don't feel like listening through it?

Words fail, music begins

Quick, design the perfect loudspeaker—No, not some gigabuck state-of-the-art monstrosity, but an affordable speaker that everybody could rush out and buy. It would be compact and unobtrusive. It would have broad frequency response, but not overwhelm the average living room. You'd be able to drive it with modestly priced gear. And it would sound good—so good that you'd never want to stop listening to music through it.

That sounds pretty close to a description of the Ruark Templar. If the Ruark deviates from the ideal of the "perfect loudspeaker," well, so does every other speaker I've ever heard—even the hideously expensive jobbies. But its amiability, articulation, sweet tonal balance, and exceptional ability to portray music as a moving (pun intended) experience make it an easy speaker to love.

Why settle for one you merely like?

Footnote 2: If you think you can't make music with two or at least three tones, try singing "Three Blind Mice"—doggerel though it may be, it still proves the point.

- Log in or register to post comments