| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

The relationship between ultra low frequencies and increased midrange palpability and clarity underscores the necessity for the lowest foundation air movement---if one is to put into the listening environment all the overtones found in the actual recorded space.

One forgets that even human speach has a percussive component which releases sub bass air movement. A plosive consonant has a leading edge of compressed air as it is sounded. No wonder the lack of ultra low frequencies robs typical playback of it's "realness."

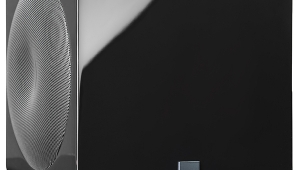

One has to experience a properly understated $9000 add-on like the Rel to understand why you would actually NEED such a thing. Of course then it is too late and you are ruined for life.